An international team of physicists has developed a method for taking ultrafast “sonograms” that can track the structural changes that take place within solid materials in trillionth-of-a-second intervals as they go through an important physical process called a phase transition.

Common phase transitions include the melting of candle wax before it burns and dissolving sugar in water. They are purely structural changes that produce dramatic changes in a material’s physical properties and they play a critical role both in nature and in industrial processes ranging from steel making to chip fabrication.

The researchers have applied this method to shed new light on the manner in which vanadium dioxide, the material that undergoes the fastest phase transition known, shifts between its transparent and reflective phases.

Many of these transitions, like that in vanadium dioxide, take place so rapidly that scientists have had difficulty catching them in the act. “This means that there is a lot that we still don’t know about the dynamics of these critical processes,” said Professor of Physics Richard Haglund, who directed the team of Vanderbilt researchers who were involved.

To build a more complete picture of this phenomenon in vanadium dioxide (VO2), one of the most unusual phase-change materials known, Vanderbilt researchers collaborated with physicists at the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society in Berlin, who have developed the powerful new technique for obtaining a more complete picture of ultrafast phase changes. Details of the method, which can track the structural changes that take place within materials at intervals of less than a trillionth of a second, are reported in the Mar. 6 issue of the journal Nature Communications.

New details on nature’s quickest phase-change artist

Vanadium dioxide shifts from a transparent, semiconducting phase to a reflective, metallic phase in the time it takes a beam of light to travel a tenth of a millimeter. This phase change can be caused by heating the material above 150 degrees Fahrenheit (65 degrees Celsius) or by hitting it with a pulse of laser light.

VO2 is one of a class of materials now being considered for use in faster computer memory. When mixed with suitable additives, it makes a window coating that blocks infrared transmission on hot days and reduces heat loss during cool periods. In addition, it has potential applications in optical shutters, sensors and cameras.

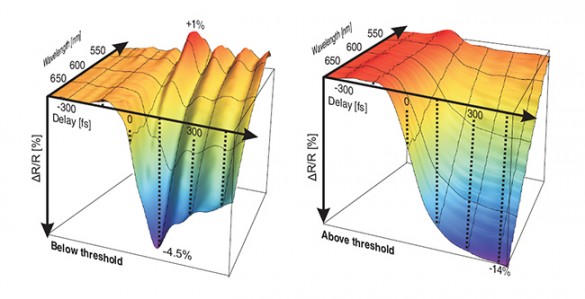

“With this new technique, we were able to see a lot of details that we’ve never seen before,” said Haglund. These details include how the electrons in the material rearrange first and then are followed by the movement of the much more massive atoms as the material shifts from its semiconductor to metallic-phase orientation. These details provide new information that can be used to design high-speed optical switches using this unique material.

Laser-based method tracks phase changes in ultra-short intervals

The new method is a variation on a standard method known as ‘pump-and-probe.’ It uses an infrared laser that can produce powerful pulses of light that only last for femtoseconds (millionths of a trillionth of a second). When these pump pulses strike the surface of the target material, they generate high-frequency atomic vibrations determined by the material’s composition and phase. These vibrations change during a phase transition so they can be used to identify and track the transition in time.

At the same time, the physicists split off a small fraction of the infrared beam (the probe), convert it into white light and use it to illuminate the surface of the target. It turns out that these lattice vibrations produce changes in the material’s surface reflectivity. As a result, the physicists can track what is happening inside the material by mapping the changes taking place on its surface.

The situation is analogous to hitting a gong with thousands of tiny microscopic hammers. The sound each hammer makes depends on the composition and arrangement of the atoms in the part of the gong where it hits. If the composition and arrangement of the atoms changes in one of these areas, then the sound the hammer makes also changes.

“The real power of this technique is that it is sensitive to atomic changes inside the material which are usually observed using expensive large-scale X-ray sources. Now we can do the experiment optically and in the lab on a tabletop,” said Simon Wall, an Alexander von Humbolt fellow at the Fritz Haber Institute.

Vanderbilt graduate students Kannatassen Appavoo and Joyeeta Nag fabricated and characterized the vanadium dioxide thin films; Simon Wall, Daniel Wegkamp, Laura Foglia, Julia Stähler and Martin Wolf at the Fritz Haber Institute directed the laser experiments and subsequent data analysis.

The project was funded by grants from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and the National Science Foundation.