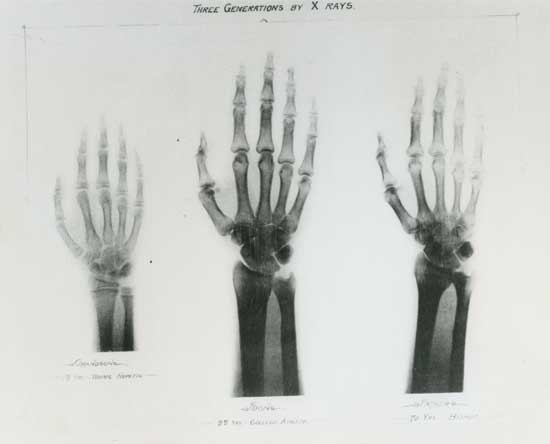

Following German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen’s discovery of X-rays in late 1895, scientists around the world began experimenting with the new technology. Among them was Vanderbilt physics professor John Daniel, who built his own X-ray device using an induction coil and Crookes tube. In February 1896, Daniel was asked to use his device to help locate a bullet in the head of a child who had been accidentally shot. To test the device and ensure the procedure’s safety, Daniel’s colleague, chemistry professor William Dudley, volunteered to first be X-rayed himself.

The men sandwiched a metal coin between one side of Dudley’s head and a photographic plate. They positioned the X-ray tube a half-inch from the other side of his head and exposed the plate for one hour. The experiment produced no image, but led to a fundamental discovery about X-ray exposure, which Daniel documented in a letter to the editor of Science magazine in March 1896: “Twenty-one days after the experiment, all the hair came out over the space under the X-ray discharge. The spot is now perfectly bald, being two inches in diameter. This is the size of the X-ray field close to the tube. We, and especially Dr. Dudley, shall watch with interest the ultimate effect.”

Fortunately, Dudley suffered no long-term effect. He served as the university’s first dean of medicine and is known as the father of Vanderbilt athletics. Daniel enjoyed a more than 40-year career at Vanderbilt. It would be decades before the scientific community fully realized the dangers – and even greater benefits – of X-rays.