The Vanderbilt Center for Neuroscience Drug Discovery announced Dec. 15 that new drug candidates for schizophrenia generated from its ongoing collaboration with Janssen Pharmaceutica, Nev., are now entering the stage of preparation for first-in-human clinical testing.

“This is a major step forward in the evaluation of this approach as a potential treatment for major psychiatric diseases. It could lead to a fundamental advance in the treatment of schizophrenia,” said P. Jeffrey Conn, co-director of the Vanderbilt Center for Neuroscience Drug Discovery.

“This is our goal, to advance patient care,” said Jeff Balser, vice chancellor for health affairs and dean of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “What better way to do that than to translate top-notch science and discovery into novel therapeutics.”

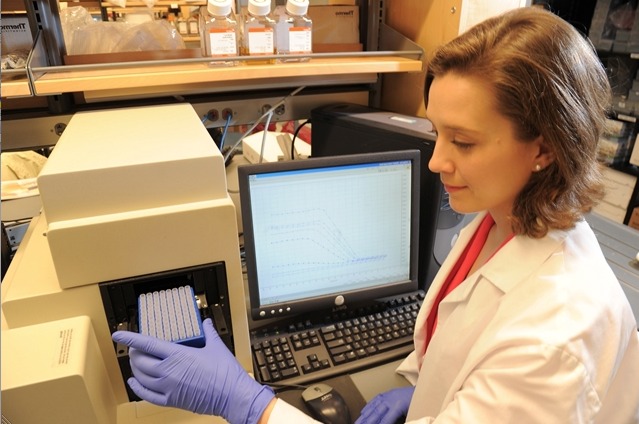

The progression of new drug candidates resulting from the agreement with Janssen is the latest evidence that a new collaborative model for drug discovery pioneered at Vanderbilt may help identify and develop innovative candidate drugs for treatment of major brain disorders, said Conn, the Lee E. Limbird Chair in Pharmacology.

The Janssen agreement is especially unique. “It really has been a team effort with dedicated efforts of chemists, biologists, and translational scientists on both sides,” Conn said.

More than 2 million Americans have schizophrenia. Current antipsychotic agents can reduce hallucinations and delusions, he said, but they are less effective in relieving cognitive deficits and other disabling symptoms, including social withdrawal.

Conn, center co-director Craig Lindsley and their colleagues have pioneered the use of “allosteric modulators” to adjust the activity of neurotransmitter receptors in the brain. Rather than activating receptor activity directly, these compounds work like dimmer switches in electrical circuits and induce more subtle changes in receptor function than are seen with traditional receptor agonists.

The target in schizophrenia is a receptor for the neurotransmitter glutamate, called mGluR5, which regulates brain circuits that are disrupted in schizophrenia patients. The drug candidates developed by Vanderbilt and Janssen scientists increase receptor activity and are effective in preclinical models that suggest the possibility of achieving efficacy in schizophrenia patients.

In separate efforts, Vanderbilt recently announced discovery of drug candidates that could relieve symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and fragile X syndrome, the most common genetic cause of autism. For each of these programs, early support by the National Institutes of Health was critical for establishing the basic science underpinnings that encouraged further investment in drug discovery.

“This really does show that this new model (of drug discovery) can work,” Conn said. “It is critical that academic scientists be fully committed to systematically advancing basic research findings to facilitate discovery of novel treatments for unmet clinical needs.”

Media contact: Craig Boerner , 615-322-4747