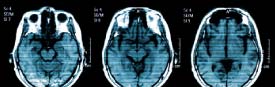

Brain scans of adolescents with dyslexia can be used to predict the future improvement of their reading skills with an accuracy rate of up to 90 percent, new research indicates. Advanced analyses of the brain activity images are significantly more accurate in driving predictions than standardized reading tests or any other measures of children’s behavior.

Brain scans of adolescents with dyslexia can be used to predict the future improvement of their reading skills with an accuracy rate of up to 90 percent, new research indicates. Advanced analyses of the brain activity images are significantly more accurate in driving predictions than standardized reading tests or any other measures of children’s behavior.

The finding raises the possibility that a test one day could be developed to predict which individuals with dyslexia would most likely benefit from specific treatments.

“This approach opens up a new vantage point on the question of how children with dyslexia differ from one another in ways that translate into meaningful differences two to three years down the line,” said Bruce McCandliss, Patricia and Rodes Hart Chair of Psychology and Human Development at Peabody and a co-author of the report. “Such insights may be crucial for new educational research on how to best meet the individual needs of struggling readers.”

The research was primarily conducted at Stanford University and led by Fumiko Hoeft, associate director of neuroimaging applications at the Stanford University School of Medicine. In addition to McCandliss, Hoeft’s collaborators included researchers at MIT, the University of Jyväskylä in Finland and the University of York in the United Kingdom.

“This finding provides insight into how certain individuals with dyslexia may compensate for reading difficulties,” said Alan E. Guttmacher, director of the National Institutes of Health’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which provided funding for the study.

“Understanding the brain activity associated with compensation may lead to ways to help individuals with this capacity draw upon their strengths,” Guttmacher said. “Similarly, learning why other individuals have difficulty compensating may lead to new treatments to help them overcome reading disability.”

The researchers used two types of brain imaging technology to conduct their study. The first, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), depicts oxygen use by brain areas involved in a particular task or activity. The second, diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging (DTI), maps white matter tracts that are the brain’s wiring, revealing connections between brain areas.

The researchers adapted algorithms used in artificial intelligence research to refine the brain activity data to create models that would predict the children’s later progress. Using this relatively new technique, the researchers could use the brain scanning data collected at the beginning of the study to predict with more than 90 percent accuracy which children would go on to improve their reading skills two and a half years later.

In contrast, the battery of standardized, paper-and-pencil tests typically used by reading specialists did not aid in predicting which of the children with dyslexia would go on to improve their reading ability years later.

The study is part of a rapidly developing field of research known as “educational neuroscience” that brings together neuroimaging studies with educational research to understand how individual learners differ in brain structure and activity and how learning can drive changes at the neural level.

“This latest study provides a simple answer to a very complex question—what can neuroscience contribute to complex issues in education?” McCandliss said. “Here we have a clear example of how new insights and discoveries are beginning to emerge by pairing rigorous education research with novel neuroimaging approaches.”

The research was published in December in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. It was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Stanford University Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Child Health Research Program, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Richard King Mellon Foundation.