Colin Dayan follows the legal trail to non-personhood

The law guarantees our rights. We can vote, say what we want, go where we please and do as we see fit. It’s all there in the Bill of Rights and other famous documents, right?

Not so fast.

What about detainees at Guantanamo Bay? How about a prisoner locked in solitary confinement indefinitely? They have some rights, don’t they?

Not necessarily.

There are any number of circumstances in which people can effectively lose some or most of their basic rights, says Colin Dayan, the Robert Penn Warren Professor in the Humanities at Vanderbilt. And that doesn’t mean the law is being broken.

“It’s all absolutely legal,” she said. “[rquote]There are legal precedents dating back centuries that deprive people of personhood and turn them into something worse than objects – into anomalies outside the reach of human empathy.”[/rquote]

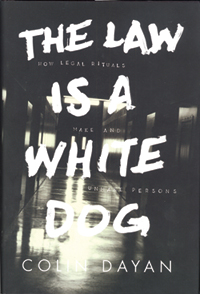

In her new book, The Law is a White Dog: How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake Persons (Princeton University Press), Dayan argues that the law has been refined so that it can be used to deny the very rights it’s presumably there to protect.

“Most people think of the law as a guild, a kind of private language, but those most oppressed by it understand its effects,” she said.

“Legal reality is ever-present and can be re-imagined by those outside the guild of lawyers,” she said. Dayan says she is trying to “give life to the dry bones of the law.”

“It takes incredible legal maneuvering,” she said. “It takes magisterial and magical words to create entities or persons who have no will, choice, no affect. But lawyers, from the time of slavery to our post-9/11 world, have gone to great lengths to bring this transformation about – especially in the cases of those thought unfit, expendable or threats to the status quo.

“After 9/11 we started hearing about things like indefinite detention, evasion of due process claims and cruel, inhuman treatment” for those deemed terrorists and labeled “unlawful enemy combatants,” the kind of persons who have lost “the right to have rights,” Dayan said.

The Law is a White Dog centers on how the law and its rituals define a “person.” Dayan finds that legal personhood applies to everything from slaves to ghosts to dogs to detainees. In the “savage logic” of what she describes as “rituals of deprivation,” Dayan focuses on slaves, animals, criminals and detainees who are disabled by law. She believes the felon made “dead in law” is a continuing effect of dehumanizing practices of punishment.

The definition of a person “can be more slippery under the law than a lay person may believe,” she said. For instance, most people believe that when slavery was legal in the United States, the law considered slaves as property. Actually, “the really awful legal practice was to contrive entities that were both persons and property – creatures of law that were outside the realm of civil life. That was the horror.

“So, to be a person can mean a number of things,” Dayan said. “[rquote]You can be a person and still be depersonalized. Today, larger and larger groups of persons are being created who legally no longer have the attributes of will and personality, something like the ‘living dead.’”[/rquote]

We all run the risk of being labeled a “depersonalized person,” Dayan said. “The poor, the racially suspect and the politically powerless are particularly vulnerable. Nowhere can legal force be so powerfully understood as in its effects on those least welcome in our society – whether ghosts, dogs, slaves, felons or any person tagged as extraneous.

“We are creating a phantasm of criminality,” she said. “That’s most obvious in Guantanamo, but it’s also true in our ‘supermax’ prisons, where prisoners are placed in indefinite solitary confinement based on what prison officials fear they might do, rather than anything they’d already done.”

The incarceration of “dangerous terrorism suspects” on American soil without due process of law trades on the promise of security, she said.

“This new global logic of punishment offers democracy while dispensing with judge and jury,” she said. “We’re in a difficult world, experiencing a brutality that is made possible because of language – words plied with civility that mask continued injury and violence.”

The white dog of the book title challenges expectations about the law, “putting laws in the courts of sorcery and permitting magic to find itself in the temple of law.”

“The white dog wanders through the night and captures and transforms a human personality,” she said. “Like the dog that haunts the pages of this book, the residues of terror are never really dead and gone but survive and always find new bodies to inhabit, new persons to target.

“When the police – or the laws – were coming to get you, I was warned, growing up in Atlanta, about the flash of white, the dog, that could devour. The white dog is after you, and it can steal your soul, tear at your flesh, thieve your mind.”