Two hundred and twenty-five years is a long time for an institution to survive. Founded as Davidson Academy in 1785, what is now Vanderbilt’s Peabody College initially existed under various names—Cumberland College, University of Nashville, State Normal College of Tennessee, Peabody Normal College. During those years, Peabody’s primary innovation was its continued existence in a region not always responsive to higher education.

The Peabody Education Fund was established by George Peabody in 1867 to promote and encourage education in the South following the Civil War. It was not until 1907 at the liquidation of the fund that the beginnings of the Peabody we know today—George Peabody College for Teachers—came into being. From that point, and at Peabody’s present location (which was the site of another institution of higher learning, Roger Williams University), the history of Peabody as a highly regarded school of education began to take shape.

Starting from the modern era in 1914, Peabody’s purpose was to serve as an agent for educational reform, particularly in the South, where the infrastructure for education had fallen apart. Peabody worked to train educators who could better the lives of students and their families, using schools as the centerpiece to initiate social reforms and bringing the South to more equal footing with the rest of the country. On the way, innovative new ideas were developed. Peabody’s accomplishments soon took on national and international stature.

Emphasis on putting research into action and theory into practice has always been Peabody’s strength. There have been many educational innovations that have evolved from research done at Peabody. In these few pages, we showcase seven innovative ideas developed at Peabody that continue to leave a mark on the world of education.

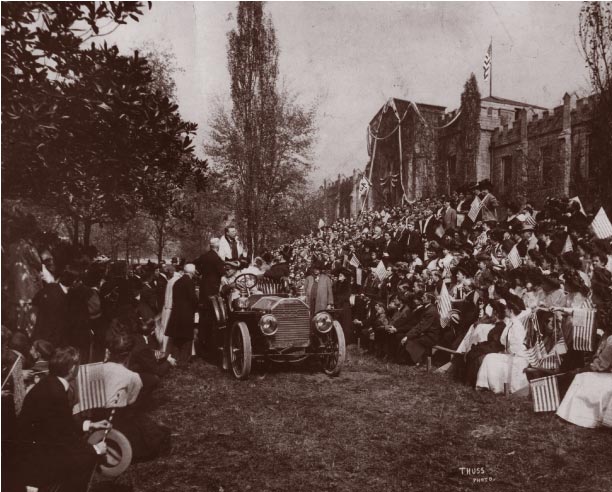

Knapp Farm

In 1915, one year after Peabody welcomed students to its present-day location, its landscape was dotted with chicken coops, a vegetable garden and a barn. The latest in farm equipment was on display in the basement of the Home Economics building and its most eminent professor was the country’s leading horticulturist—all in an effort to live up to the reforms suggested by the Country Life Commission created by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Improving the life of rural Americans, particularly those in the South, became an important mission for Peabody. The hero of this movement was Seaman A. Knapp, a federal appointee charged with promoting Southern agriculture. His work eventually led to the establishment of the Cooperative Extension Service that supported farmers and home demonstration agents.

Bruce Payne, Peabody’s first president, was an enthusiastic supporter of Knapp’s work and wanted to create a Knapp School of Country Life on the campus. The funds for the school never materialized, but Payne was able to purchase 300 acres east of Nashville (near the present-day Nashville International Airport) for a demonstration farm.

The farm flourished with a 25-acre orchard and fields used to experiment with crops suited to the local climate. The farm’s pride and joy was its dairy and herd of purebred Holsteins.

Visitors flocked to the farm from all over the South. It provided part-time work for students and fresh food for the school cafeteria. However, the farm that was established to honor Knapp fell victim to his vision. As the Cooperative Extension Service grew, the need for the demonstration farm waned. By the 1930s the dairy operation was the only viable part of the farm.

Peabody held on to the herd until 1959 when it was sold. The land was sold in 1965 for $1 million. Though Peabody no longer has any component quite like Knapp Farm, its faculty continues to do important research leading to both rural and urban social reforms.

For more, visit: http://snipurl.com/knappfarm

Lloyd Dunn and the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test

The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test doesn’t look like a game changer.

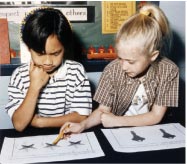

It could easily be mistaken for any classroom material—it’s just an easel with a series of pictures, four to a page. But this simple test, developed in 1959 by Peabody’s pioneering Lloyd and Leota M. Dunn, is still used worldwide and is considered the standard bearer for a fast, accurate measure of how well someone understands language.

Because test-takers answer by simply pointing at a picture, the PPVT can be used with children as young as 2 and adults as old as 90. The 15-minute test accurately measures the receptive vocabulary skills of people with reading or speech problems, multiple physical impairments, developmental disabilities and those who are emotionally withdrawn.

“I don’t know of a measure that’s used more than the PPVT,” says Ann Kaiser, a professor of special education and holder of the Susan Gray Chair in Education and Human Development. “We use it to show early growth in children’s vocabulary skills. It’s a good indicator of language ability when they’re young, and it’s an easy test to respond to—they just point to the named picture.”

“The PPVT measures receptive language, which is a person’s ability to comprehend a message,” said Stephen Elliott, Dunn Family Professor in Educational and Psychological Assessment. “It’s also a good proxy for measuring intelligence as commonly defined.”

Lloyd Dunn was one of the “scholars with a social conscience” who helped found the Kennedy Center in 1965. He established the first doctoral program for special education in the South, and served as its chair from 1953 until 1967. Lloyd Dunn and his wife Leota collaborated on a number of assessment and instructional devices first published in the 1950s and ’60s, including the Peabody Individual Achievement Test, Peabody Language Development Kits and Peabody Early Experience Kits. Their son, Douglas M. Dunn, who was a researcher at Bell Labs and later dean of the Carnegie-Mellon University business school, recently collaborated on the fourth revision of the PPVT test, keeping the 1950s test relevant for the 21st century.

For more, visit: http://snipurl.com/lloyddunn

Susan Gray and Head Start

Susan Gray and Head Start

Susan Gray was a small woman, but her influence on education was huge—spanning decades and affecting not only teaching, but policy and decision-making on a national scale. Perhaps even more important, her work led to programs that improved the lives of millions of underprivileged and underserved children.

Paul R. Dokecki, director of Peabody’s Community Research and Action doctoral program, was a Peabody student when Susan Gray was breaking new ground with the Early Training Project. That project—an early educational intervention program for at-risk preschoolers—grew from an experimental summer program to one of international repute.

In 1965, Gray co-founded the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center. Soon after, her work with the Early Training Project caught the eye of Sargent Shriver, head of the Office of Economic Opportunity, a government program started by Lyndon Johnson in 1964 to fight the “war on poverty.”

“In the 1960s there was optimism about what education and research could do,” Dokecki says. “Shriver always credited the work of Susan Gray and the Early Training Project as being the intellectual stimulus for the Head Start program.”

In 1970, Gray recruited Dokecki to come back to Peabody as her associate director of the Demonstration and Research Center for Early Education or DARCEE, an extension of the Early Training Project. Dokecki succeeded Gray as director upon her retirement.

“People came from all over the world to our training workshops on campus,” Dokecki says. “This was a major research project. We had more than a hundred staff members and a million-dollar budget, and this was back in the early 1970s. Susan Gray created all that.”

In later years, scholars studied the long-lasting effects on children who had been in the program.

“There was a national effort to see how the children were doing in their 20s,” Dokecki says. “We found that kids who had been in the program were less likely to have been in special education, less likely to have been incarcerated or to have children born out of wedlock.”

For more, visit: http://snipurl.com/susangray

READ 180

READ 180

Millions of students now call themselves good readers thanks to READ 180, a reading intervention program developed at Peabody. By combining individualized computer-guided instruction, video and sound teaching methodology, READ 180 has proved to be the key for struggling middle- and high-school students across the country.

Ted Hasselbring, Peabody research professor of special education, led the genesis of READ 180 in 1985, when he won a Department of Education grant looking for ways to use technology to help special education students become better readers. Results were so promising that in 1994, the Orange County (Fla.) school district brought Hasselbring and his team down to implement READ 180 in the hopes that helping struggling middle- and high-school students learn to read would lower the district’s battles with behavior problems, truancy and dropout rates.

It worked. By using the READ 180 instruction protocol of 90 minutes a day, five days a week, the school system’s dropout and behavior referral rate fell significantly while reading scores continuously rose. Word of the program’s success spread—students usually improve two to five grade levels in a year—and Hasselbring then partnered with Scholastic in 1999.

“READ 180 works because it combines Ted’s sound, proven research with our knowledge of technology and what works in the classroom,” says Margery Mayer, president of Scholastic Education. “READ 180 creates a safe place for these kids to learn and grow.”

READ 180, used in 15,000 classrooms across 50 states, is now the gold standard for middle- and high-school reading intervention programs. Hasselbring and Scholastic keep READ 180 up to date and are developing partner programs for students who need support to get to READ 180’s level and for those who are ready for the next step.

Hasselbring keeps a fat ring binder of student success stories on his office shelf. “They tell us that being able to read totally changes their lives,” he said. “It’s amazing to be a part of this.”

For more, visit: http://snipurl.com/sread180

The Adventures of Jasper Woodbury

The Adventures of Jasper Woodbury

During a close mayoral race, Jasper Woodbury, a journalist for the Cumberland City Chronicle, covers a story on how nearby Trenton plans to dump its excess garbage in Cumberland City. Two siblings, who are members of their high school’s environmental club, volunteer for the mayoral campaign of their mother, who has a plan for how to deal with the garbage. The day of the election, they must hurriedly fill in for a volunteer who has an emergency appendectomy. They must now figure out the schedule for sending get-out-the-vote vans.

The challenge: Find the best plan for the morning and afternoon rush-hour time slots, including when to tell drivers to be at the rental agency to pick up and return the vans.

This is a synopsis from one of the 12 videos that comprise The Adventures of Jasper Woodbury. Developed at Peabody’s Learning Technology Center in the early ‘90s, the series uses real-world problems and technological interactivity to teach mathematical concepts to middle school students around the United States. In studies of students who have encountered Jasper and his adventures in the classroom, assessments have shown that impressive gains in understanding arithmetic, algebra, geometry and measurement were made in comparison with students who did not work on these concepts using the series. Their abilities to work with others and to communicate design ideas also improved.

In the episode above, students are given information about how long it takes to drive from the rental agency to the polling places, how much gas costs at a certain service station on the way, how much each van costs according to its size (how many can be transported) and how many gallons of gas it holds, and aspects related to the election, such as polling results and how many votes a candidate must gain to win the election.

Students work on various adventures within the series during three to four weeks, and each episode provides material for solving a number of challenges.

Mark F. Klassen, a sixth-grade math teacher at Meigs Magnet Middle School in Nashville, uses the videos in his classes. “I have found that The Adventures of Jasper Woodbury teaches math in authentic settings that support students’ reasoning, problem solving and communication skills. The way that Jasper introduces the ‘challenges’ in conjunction with the story leads students to believe they could encounter and solve these problems in real life.

“Math then becomes a life skill,” Klassen says, “instead of an algorithm to be used to solve a series of problems that only exist in books.”

For more, visit: http://snipurl.com/jasperwoodbury

Responsiveness to Intervention

Responsiveness to Intervention

Forty years ago, a student who experienced severe difficulty in learning to read or in learning math would not have been diagnosed with a learning disability. Today, nearly 50 percent of all students with disabilities are identified as learning disabled. Learning disabilities, which span reading, mathematics and written expression, have traditionally been identified using discrepancies between IQ tests and achievement scores.

Douglas Fuchs and Lynn Fuchs, Nicholas Hobbs Professors of Special Education and Human Development, have been instrumental in developing a multitiered approach for identifying students with learning disabilities called responsiveness to intervention or RTI. Using instructional methods of increasing intensity, such as validated small-group tutoring, as well as progress-monitoring methods for indexing a student’s response to that instruction, RTI has gained favor as one of the best methods for identifying students with learning disabilities and for providing preventative education services.

In 2001, the U.S. Department of Education awarded a grant to Doug Fuchs, Lynn Fuchs and Don Compton, associate professor of special education, to establish the National Research Center for Learning Disabilities.

The center’s focus was to conduct research on RTI and to provide technical assistance to state educational agencies that implement RTI. Researchers have found that among the 20 percent of children at risk for learning disabilities, approximately 15 percent respond to the prevention services incorporated within RTI.

“RTI has been a useful notion to help researchers like myself and my colleagues rethink methods of identifying children at risk for severe reading and math problems,” Lynn Fuchs says. “And if we can identify them more quickly, we can help them sooner.”

For their work, Doug and Lynn Fuchs were named to Forbes magazine’s list of 14 revolutionary educators in December 2009.

For more, visit: www.nrcld.org

The National Center on Performance Incentives

The National Center on Performance Incentives

Changing minds that have been made up for more than half a century won’t be easy, but that’s exactly what Matt Springer is trying to do. Springer is the director of the National Center on Performance Incentives and assistant professor of public policy and education at Peabody.

In the 1920s the single salary schedule of teacher compensation was introduced. This method rewards teachers based on their years of experience and degrees held. By the 1950s, more than 90 percent of K-12 public schools in the United States had adopted this policy and that figure is true today as well. However, policymakers and others question whether this is really the best compensation method.

“What we’ve found is that experience and degree only account for 3 percent of the variation in teacher effectiveness,” Springer says. “That means that 97 percent of what could explain what makes a teacher effective has nothing to do with how long they’ve been teaching and what degree they’ve obtained.”

The National Center on Performance Incentives is researching an alternative compensation method—one based more on student performance.

“The design of our project is focusing more on an outcome as opposed to rewarding teachers for board certification or earning an advanced degree,” Springer says.

The just-completed three-year study shows, “We tested the most basic and foundational question related to performance incentives—Does bonus pay alone improve student outcomes?—and we found that it does not,” Springer says. “These findings should raise the level of the debate to test more nuanced solutions, many of which are being implemented now across the country, to reform teacher compensation and improve student achievement.

“We need six-figure salaries for our best teachers,” Springer says. “Until we can differentiate pay and until we can begin to recognize the highest performers, we’re not going to change the quality of our teacher workforce. Obviously those top individuals can make a whole lot more money outside of education if we stick with the current model.”

For more, visit: www.performanceincentives.org