The achievement gap in education is based on averages—average test scores, average family incomes, average performance based on race and ethnicity. On average, for example, black and Latino men are the lowest performing group on the down side of the achievement gap. Yet not all black and Latino males fall into that category. Some have defied the averages and risen above their circumstances to become successful. Jamie Graham and David Pérez are two such men.

Although every situation is different, if Graham and Pérez can serve as examples, certain common factors appear to be crucial for beating the odds of poverty and racial disparities. First, students must have someone in their lives—a parent, a guardian, a relative or a coach—who refuses to give up on them, even when the student makes bad decisions. Second, at various pivotal junctures in their school careers, a mentor, a teacher or a coach steps forward unsolicited and offers to help. Third, these students possess an innate sense of destiny, believing that if given the slightest chance, they will make the effort to succeed. And finally, these students are inherently resilient, so that whenever they get knocked down, they still struggle back up and give life one more try.

Here are two stories:

Things to Work For

Jamie Graham, Peabody Class of 2011

Born in a rough neighborhood in East Nashville, Jamie Graham was achingly familiar with tragedy as a young child. He and his younger brother Jamonte were being raised by their single mother, Jamie Denise Graham, when she was killed right before Christmas 1996. Jamie, 8, and Jamonte, a toddler, went to live with their grandmother, Hattie Graham. Jamie’s second-grade class collected money for a few presents so that Jamie would have Christmas that year. “I will always remember the teacher who did that for me,” he says.

Jamie grew into an outstanding athlete and a good student under the watchful eye of his grandmother, who always stressed what she called “the three B’s—Bible, books and ball—in that order,” and he managed to stay on track until he hit high school. In the ninth grade, he received his first D, in geometry, and although he worked hard to bring the grade up to an A by the end of that year, he had begun hanging out with the wrong crowd and getting into trouble. When he was a sophomore, he quit the football team. With only a few games left in the season, football coach Anthony Law tracked Jamie down. “You need to come back and play football,” Coach Law told him. “You’re good enough that this is going to be your ticket to college.” Perhaps because the coach made the effort to seek him out, Jamie took his advice and rejoined the team.

When you feel like you’re close to a teacher, it’s the best feeling in the world.

For the next two years, Jamie was a star athlete in both football and basketball at Whites Creek High School, and Law became his mentor, his counselor and his advocate, helping Jamie navigate through life’s rough patches. Although he had several college offers in both sports, he signed with Vanderbilt to play football, the only person from his high school class to go there. He chose Vanderbilt because he felt obligated to stay close to home. His grandmother has health issues, and Jamie has largely taken over responsibility for raising his younger brother. Also, he says: “If I get a degree from Vanderbilt, it means so much—especially in my community.”

The trek has not been easy, however. After being red-shirted his freshman year—meaning he practiced with the football team, but could not play in the games—Jamie was ready to quit school. It seemed like every week another of his East Nashville friends was killed. One year Jamie had 11 friends die, mostly in violent incidents. One of his best neighborhood friends was shot and killed while walking home. He struggled to adjust to the surreal otherworld that is life at a quiet university.

Jamie says, “It just seemed like things were being thrown at me all at the same time, and I was having tough schoolwork to deal with on top of that.” He took time off, regrouped and finally concluded that sticking it out would give Jamonte more options. “I came back, and I dedicated myself to school. I decided I had things to work for,” he says.

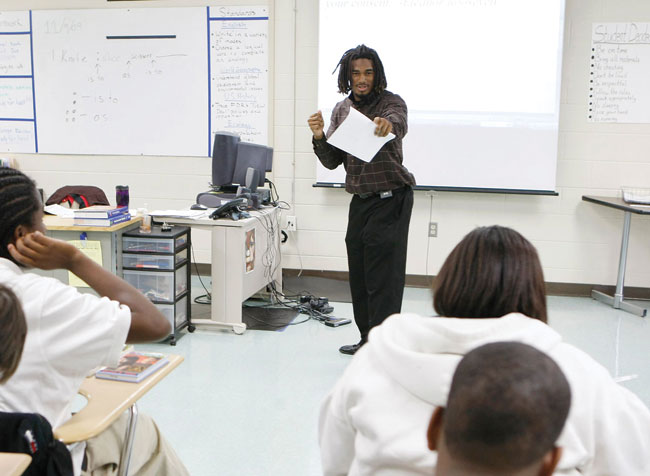

During his junior year in 2009, Jamie had a breakout season on the football field and in the classroom. An education major at Peabody, he did a teaching rotation in a special education class in East Nashville. As he began forging bonds with socioeconomically disadvantaged students who also had physical and learning disabilities, behavioral disorders, autism and emotional problems, he realized where his heart was. He switched his major to special education.

Jamie wants to be a role model for children back in his neighborhood, and he wants to pay back those teachers who were there for him. “When you feel like you’re close to a teacher,” he says, “it’s the best feeling in the world.”

He has two more years of eligibility on the football team and is scheduled to graduate in spring 2011. Depending on how football works out, he’ll either try to go pro and play in the NFL, or he might take the extra year of eligibility and get his master’s degree in education.

“I can be the first person in my family to graduate from college, and Jamonte can be the second,” Jamie says. “I want the people in our neighborhood to realize that if the Grahams can do it, and they live right across the street, then we can do it, too.”

El Logrador

David Pérez II, BS’97, MEd’01

David Pérez II began to drift off track around the time he started high school. Growing up in a low-income district of Brooklyn, N.Y., Pérez began hanging around with the wrong crowd as he reached his midteens. His mother, Enid S. Hernandez, had raised him alone, remarrying when her son was 10, although David says his stepfather did not play a central role in his life. Searching for prestige and credibility, David joined a gang. From that point forward, his life became a perilous tug-of-war between his buddies in the gang and his mother’s determination to free him from their influence.

He got into fights, got arrested for truancy and flunked nearly all his courses. One day, David learned that there had been a fight between two guys. At the end of it, members of his gang had jumped one of the guys and slashed him with box cutters. They had crossed the line, David thought, and he wanted out. However, he soon discovered that joining a gang meant that he couldn’t just leave. His former friends began stalking him, threatening to cut him up, even threatening his family. To dodge them, David would change his routine every day, going to school late and leaving classes early. He carried his own box cutter with him for protection and was expelled twice for taking it to school. He bounced in and out of schools all over New York and eventually was picked up again for truancy.

By this time, David was two academic years behind, and his mother was at her wit’s end. “She decided to pull me out of high school,” David says. “My sister was 6 and my brother was 2, and she said, ‘You’re a bad influence on your siblings. I can’t do this anymore. Go get your GED.’” This was the first time in his life he felt that his mother was giving up on him. “It shattered me,” he says.

But Enid Hernandez did not give up. She continued to search for options for her son. David ultimately wound up at Pacific High School, an alternative school for students who washed out of traditional high schools. The school was underresourced—the encyclopedia set was missing several volumes, the college catalogs were almost a decade old and library books had pages torn out. The school counselor told him: “You don’t have to be here if you don’t want to. But if you want to finish high school, we’re here to help you.”

David recalls, “I made a choice then. I was praying to God to give me one more chance.” At the end of his first semester at Pacific, he made As and Bs. When his mother saw his grades, she called the school to be sure he hadn’t stolen someone else’s report card.

To make up his missed classes and graduate on time, David overloaded on classes, attending Pacific from 8 a.m. until 3 p.m., signing up for extra independent studies and then heading off to night school. As swamped as he was with work, his grades remained excellent. Teachers at the school began to suggest to him that he should go to college, and one teacher told him about The Posse Foundation, a nationally recognized college access and leadership development program that sends diverse groups of students (i.e. posses) to highly selective postsecondary institutions. David applied and was accepted to attend Vanderbilt University. He’d never heard of it before.

Since his mother couldn’t afford to make the trip with him, David boarded a plane alone in the late summer of 1993, carrying a word processor in a box and one suitcase full of clothes.

His arrival in Nashville was marked by culture shock. “I grew up in Brooklyn around a lot of racial and ethnic groups. For me, being Puerto Rican was central to my identity. When I moved onto campus, I felt like an outsider,” he says. “The transition was very difficult. Of all my peers in Posse, I did the worst academically that first semester. I earned a 1.33 GPA, and I was placed on academic probation.”

He was so miserable that after being in college for three months, he hadn’t even unpacked his suitcase. He phoned his mother and told her he was going to leave. He was in over his head. “No,” she answered firmly. “I know you’re going to make it. You can do this.”

One of David’s friends from Posse came over, unpacked his suitcase and put away his clothes, telling him that being at Vanderbilt was rough on all of them, and he would just have to figure it out. Which he did. By the end of his second semester freshman year, his GPA had edged up to a 2.5. Semester by semester, his GPA slowly inched a little higher, by a tenth of a grade point or so each time.

Still, he felt a chronic sense of guilt that his family was sacrificing so much for him to be at Vanderbilt. While the Posse scholarship paid for most of his expenses, he knew that his mother was refusing to take out loans to support his education and was juggling her finances to come up with the needed funds. He worried that she was getting behind on rent and that his younger siblings were being denied things she could no longer afford.

One day late in his sophomore year, when David was feeling conflicted about placing such a burden on his family, he spotted a notice seeking applications for student residence assistants, or RAs, for the upcoming school year. RAs would have their housing paid for by the university and receive a stipend. The deadline was in two days. Fortuitously, the area director for his residence hall, Richard Jones, had left his door open. He noticed David standing there, came out into the hallway and asked, “May I help you?”

After David explained his situation, Jones told him that if he could get him an application and a resume, Jones would guarantee David a spot on his staff. David had never seen a resume, much less created one, so he called his mother. She didn’t know how to write a resume either, but she knew of someone in Brooklyn who might be willing to help. David was hired.

“My junior year I took flight as an RA,” he says. “I loved helping students who needed assistance. And I was the only Latino out of 20 to 25 RAs, so I found I could be a voice in this area of campus life.” Happily engaged in campus life and feeling useful, he continued to work as an RA until he graduated from Peabody in spring 1997. His last semester GPA was a 3.5, and he finally made the dean’s list.

David went on to receive his master’s degree at Peabody, worked for a while, and now is in the final stages to receive a Ph.D. in higher education from Pennsylvania State University. His dissertation research is a study of minority, particularly Latino, males from impoverished communities who have risen above debilitating life circumstances to excel in college. He does not like to speak of “achievement.” Instead he prefers the Spanish term, lograr, which is weightier than “to achieve.” It means to reap the benefits of one’s labor and exertions.

“Lograr implies a struggle or sacrifice, a price that had to be paid to be successful,” David explains. “I paid a tremendous price to be successful. My entire educational career has been a painful process.” He is now a logrador, he says, because Posse gave him immediate access to relationships with friends in similar situations and to faculty who were invested in him, even though he was ill-prepared for college. Somebody always came through for him in the clutch.

“Richard Jones was one person,” he says. “I wasn’t sure I could stay in college. But all I needed was one person to broker the deal.”

For disadvantaged students, the path to success can turn on the gentlest of exchanges—like when an adult rises from his chair, steps into a hallway and asks, “May I help you?”

And a proud, hesitant young man musters up his courage to answer, “Yes, maybe you can.”