It’s a gray winter day at Ross Elementary, an inner-city school in East Nashville that serves a high percentage of children who qualify for the free and reduced-priced lunch program, and pre-K teacher Tish Smedley is overseeing the controlled chaos of her 4-year-old students as they prepare for rest period. A slender little boy dressed in a black basketball warm-up suit enters the classroom, waits patiently and then hands her a sheaf of papers with an image on top. He is a first-grader and not one of her students.

A little confused, Smedley takes the papers and asks, “Is this for me?”

“I’m just showing you what I did,” he tells her.

Smedley realizes that he has handed her not a picture he drew, but a graph of his progress in literacy. The graph shows that every month from September 2009 to February 2010 his scores have improved, rising from a 10 to a 57.

“You’re showing me your progress! Look what you did!” Smedley gushes. “This is amazing! Are you proud of yourself?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he answers quietly.

She gives him a big hug and lets him choose a treat from a bag she has on hand for just such occasions.

Clutching his report, the boy walks out of the room—never once having so much as cracked a smile.

Pre-K students at Ross Elementary School in Nashville work with colors and shapes prior to leaving school for the summer break. Research suggests that students from disadvantaged schools are more likely to experience a “summer dip” in achievement that can aggregate so that children can become at least two years behind by the time they reach high school.

Like millions of other at-risk minority children from low-income families, this child understands on some level the seriousness, the gravity, of the spike in his test scores. He, his teachers and his school are swimming against the current, trying their best to narrow the achievement gap in education.

The achievement gap is a hotly debated topic among educational academicians and policymakers. After largely being ignored during the 1990s, it has reared up again in the new millennium when the No Child Left Behind Act forced schools to disaggregate the numbers and analyze standardized test scores of students from different backgrounds and social classes—including white, Asian, African American, Hispanic, Native American and low-income children. Like a mirror reflecting an ominous truth, the numbers show that, on average, poor black and Hispanic children are not performing as well as their white and Asian peers. In some cases, the discrepancies are chilling.

“On average, white children outperform black children on every measure of academic skills,” says Richard Rothstein, research associate at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C. “It’s not just in reading and math, but also in science and history, on physical fitness, on behavioral outcomes, and arts and music. And the cognitive gap is as large before children enter kindergarten as it is during their school years. Children from impoverished social and economic communities don’t come to school as prepared to learn as middle-class children. This suggests that factors related to social class, not differences in school quality, are primarily responsible for fostering differences in academic performance between blacks and whites.”

A national test of 15-year-olds conducted by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) found that black high school sophomores in the United States scored at the 26th percentile in reading, and at the 25th percentile in math and in science, compared to their white peers who scored at the 62nd percentile in each of these subject areas. Sadly, in too many instances, poor and minority children are graduating from high school with no more than an eighth-grade education.

Joseph Murphy

According to Joseph Murphy, Frank W. Mayborn Professor at Peabody, and author of The Educator’s Handbook for Understanding and Closing Achievement Gaps (see right), these children often spend their entire lives trying to overcome what they did not master in school. “If you’re on the wrong side of the gap, you’re more likely to drop out of school, less likely to enroll in college, and more likely to drop out if you do enroll in college,” Murphy says. He is studying any and all issues that might improve educational quality, because not to fix the problem will have unforgivable consequences. “You can’t systematically parcel students into a ‘Kids We Left Behind’ category. That’s reprehensible. It’s a social justice issue, too. You are damning these kids to second-class citizenship in nearly every dimension we have.”

Minority and low-income children are markedly “school-dependent,” meaning that it’s difficult for them to access resources and opportunities outside of school to help them overcome deficiencies in their education. “If you’re a poor kid and you’re in a bad school, you’re in a world of hurt,” Murphy says, “because you don’t have a lot of other support systems that are going to make up for it.”

The Education Equality Project, a bipartisan advocacy group, views the achievement gap not only as an indicator of an ugly underbelly in American society, but also as the most important civil rights challenge facing this generation. Although there are some exceptions, the evidence is clear that, in general, urban families with the lowest income tend to be zoned to schools with the least resources. Teachers are often inexperienced and are quick to transfer or burn out. Students in these schools are disproportionately referred to special education and underreferred to gifted programs. In many of these city schools—Nashville, Cleveland, Indianapolis, to name a few—the high school graduation rate is less than 50 percent. Yet a few miles away in more affluent suburban neighborhoods the graduation rates are above 90 percent.

“What tugs at me is the disparity of public education between schools. They should be equitable,” says Sharon Shields, professor of the practice of health promotion and education. “We are only going to benefit as a society if the opportunity is there for all children to reach their potential. We have to ask ourselves, what are the barriers to achievement?”

Stagnating trends and the summer dip

The achievement gap was first acknowledged in the 1950s, when the federal courts began addressing issues of disparity through its ruling on Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka. From the late 1960s through the mid-1980s, the United States made a concerted effort to tackle educational inequality through desegregation policies and social, health and welfare programs. Leaders feared the U.S. was losing its international competitive edge with the rise of the Soviet Union’s space program and Japan’s emergence as an economic power. According to a 2009 Report by the Center on Educational Policy, for 25 years the black-white and Latino-white gap fluctuated but essentially trended upward across all grade levels, hitting its narrowest mark in the late 1980s. Then it began to widen again. The lines have now essentially stagnated. In 2008, the gap was still quite large—ranging from 16 to 29 points on the NAEP 500-point scoring scale.

Experts dispute the causes for this stagnation, although Rothstein blames it on inattention. “The gap narrowing may have slowed because we lost focus on social inequality,” he states. “Our public schools are more racially imbalanced than at any time in this country since desegregation, because our neighborhoods are more hypersegregated than they ever were. Over the past two decades we have actually rolled back social reform.”

His data indicate that family income is only one factor in a myriad of social class issues that are driving down achievement. Rothstein says, “Typically, black and white children, even if they come from families of similar incomes, are not similar in their performance on these measures of achievement. Among black and white families with similar incomes, whites have greater wealth, better housing and better health outcomes. So it’s not surprising that the test scores of white children will be higher, even after controlling for current family income.”

To compound the challenge, disadvantaged schools are trying to hit a moving target. Stagnation in the achievement gap is actually a by-product of shifts among the various groups. In the past decade, minority and low-income students, who started off behind at the beginning of each school year, made significant gains in achievement levels, but so did their white and Asian peers. The result has been a zero-sum gain.

Ellen Goldring

Ellen Goldring, Patricia and Rodes Hart Professor of Educational Policy and Leadership, uses the analogy of two trains that need to arrive at the same destination at the same time. “If one of the trains gets stuck in the snow and the other train keeps going, then for the one that’s stuck in the snow to reach the end on time, it has to go much faster,” she explains. “So, it’s not just a matter of making up a year’s growth if you’re behind. It’s that you have to learn at a faster rate.”

In many cases over the course of the nine-month school year, these children seem to be learning at a faster rate and making up ground on their more advantaged counterparts. What is pulling them down, researchers now say, is how much they lose over the summer. Some call this phenomenon the “summer dip.” Marc Stein, PhD’09, assistant professor in the School of Education at Johns Hopkins University, studied one of the largest school districts in the Southeast that encompasses a wide range of schools from the most affluent to those with high percentages of children receiving free/reduced lunch to see how the summer dip affected children in grades two through five. He found that, on average, regardless of neighborhood, race or class, all students lost ground during the summer. However, students living in middle and higher socioeconomic status neighborhoods lost much less ground than students in more disadvantaged contexts. One possible explanation is that by living in a more advantaged context, students may be privy to educationally meaningful experiences during the summer that compensate for not being in school. Disadvantaged students may not have these same experiences and exposures.

“The schools are helping disadvantaged students make up ground to close the gap during the school year, then the summer happens and the school has to bring them up again,” Stein says. “By the end of the fifth grade in this district, the achievement gap is wider than it was at the end of second grade.” Cumulatively, poor students are losing more ground over the summers than they are able to make up over the school years. Other research suggests that by the time some students reach high school, they may be at least two academic years behind.

“This really highlights the need to consider summertime in these evaluations when we talk about school effectiveness,” Stein says. “When we only use spring test administration to judge effectiveness, we lose sight of the impact of that intervening summer.”

Certain studies claim that the educational experience of the mother is one of the strongest influences on a child’s school performance. In turn, one of the major causes of the achievement gap is the intellectual environment in the home. Researchers found that children ages 0 to 3 from middle-class families were exposed to much more complex language in their home environments and heard three-and-a-half times more words per hour in their daily backgrounds than preschool-aged children from low-income homes. In short, the education achievement gap arises long before a child ever goes to school.

Parenting styles are also seen as contributing factors. Tish Smedley insists that her inner-city parents care about their children’s future, but many don’t know how to promote early childhood education. Nearly all of her students have at least one working parent, albeit often in low-wage jobs. In many cases, the problem is that these children have spent years in daycare devoid of enrichment. “I have kids who come into pre-K, and they don’t know how to hold a pencil or a crayon. They don’t know how to hold a pair of scissors,” she says. The standards for kindergarten are so high now, that if these children go straight to school without first spending a year in pre-K, she says “then kindergarten just slams them.”

It is unfair, experts argue, to lay the blame at the foot of the schools and expect teachers to remedy all these deep-seated, complex and cumulative ills. “Schools didn’t cause the problem, and we can’t expect schools to fix the problem alone,” Murphy says. “We need a more robust attack on it.”

Yet even if policymakers agree with this data, wholesale social reform will entail a long, hard-fought, multipronged battle. In the meantime, figuring out how to narrow the gap will continue to fall into the lap of school systems.

Charter, magnet, DoDEA schools and parental choice

For decades low-income parents have sought ways for their children to escape traditional inner-city public schools for better educational opportunities. The charter school movement grew out of this desire, allowing individual schools more freedom to implement innovative teaching strategies to help disadvantaged students. Some charter school networks, like the national KIPP Academy, YES Prep Academy in Houston (see Is the Answer YES?), IDEA Public Schools located near the Texas-Mexico border, and Harlem Children’s Zone Promise Academy in New York have all been recognized for their success in narrowing the achievement gap for at-risk students. Unfortunately, other charter schools have not come close to meeting those goals.

The magnet public school initiative was an even earlier appeal to parental choice. Magnet schools came on the scene in the 1960s to mitigate against “white flight” during the era of integration and busing. Over time, magnet schools began evolving around central academic themes, like math and science, the performing arts or the liberal arts. In this way, city schools could draw students of diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds from a variety of enrollment zones, because they shared specific academic interests. In the United States many more magnet public schools than charter schools are operating today, although charter schools tend to grab the headlines.

Claire Smrekar

Having studied the effect of parental choice on education, Ellen Goldring states that neither traditional public, magnet nor charter schools are panaceas to the achievement gap. However, she says, across all types of schools researchers have found a handful of “enabling conditions” that appear to form the essential ingredients for helping disadvantaged students achieve. First, these schools have strong school leadership, meaning that the principal and administration have a focus on school improvement. Second, they implement the tactic known as professional learning communities, meaning that teachers collaborate on subject matter to help students learn, draw connections and analyze. Third, all school professionals relentlessly focus on the academic achievement of their students, adding rigor to the curriculum. And finally, they prioritize teacher efficacy by giving teachers the tools and support to meet the needs of their students.

Claire Smrekar, associate professor of public policy and education, has studied children educated in the Department of Defense Educational Activity (DoDEA) system, located on the grounds of military posts in the U.S. and overseas. Using evidence that black and Latino children in these schools out-perform nearly all other minority students in the country, she initiated a study to explain the narrower achievement gap among these students—given that white and Asian DoDEA students performed well also. Smrekar discovered that the families of these students had many of the same characteristics of inner-city families: the vast majority of parents were enlisted, rather than officers, and therefore were paid low wages, qualifying the children for free/reduced price lunch; most parents had no more than a high school education; the families tended to be unstable, with high mobility, a high rate of divorce and blended families, and also a high rate of domestic violence; and they lived in military housing, which is similar to public housing in that living spaces tend to be small and cramped.

The differences between the military bases and inner-city conditions were equally notable, however. For example, military neighborhoods were safe, characterized by low crime, areas of green space, playgrounds and recreational facilities. Also, living on the base meant that at least one parent had full and stable employment. Finally, family members had easy access to a medical facility and to quality health care.

In addition, the DoDEA schools met all the criteria listed by Goldring—leadership at the top and high-quality teachers, an emphasis on academic achievement, collaboration among teachers across subject matter, and ample resources so teachers could meet the needs of students dealing with difficult family situations.

“We argue repeatedly that there are important lessons to be learned and models of organizational coherence and continuity that could be adopted from the DoDEA system,” Smrekar says. “While we acknowledge the differences, if you look at the way the school reaches in to families and provides systems of support and a spirit of caring, then it’s clear that there is much to be learned and much to be valued.”

Teachers, gifted students and the role of encouragement

Given that high teacher quality is one of the essential components for narrowing the achievement gap, policymakers have been casting about for ways to find these top-notch individuals. Teach for America, which enlists college graduates to fulfill two-year stints teaching in disadvantaged schools, has been rattling the cages of the traditional recruitment process. With 24,000 recruits, however, TFA is not nearly big enough to meet the need. The American public school system requires almost 4 million teachers to educate all its children.

Ronald F. Ferguson, senior lecturer of public policy and education at Harvard Graduate School of Education, conducted a 2002 study on racial and ethnic disparities where schools were reportedly excellent. He found that when high school students were asked what motivated them to work hard in school, white and Asian students often cited teacher demand. However, minority, and particularly black students, almost always pointed to teacher encouragement as their reason for putting forth extra effort.

Donna Ford

Donna Ford, professor of special education, says: “There’s a saying in the black community that goes, ‘Black kids don’t care what you know until they know that you care.’ Research consistently shows that black kids want those relationships with their teachers. Relationships matter.”

Ford’s primary research focus has been on the underrepresentation of African American students in gifted and AP classes. She found that a significant proportion of low-income, black and Hispanic students—including some who defied the odds and scored well on standardized tests—would be better served in gifted programs. According to the Office of Civil Rights data of 2006, more than a quarter of a million black children were not identified as gifted who should have been. Ford argues that this underrepresentation is a symptom of the larger issues of the achievement gap. “We cannot close the achievement gap without addressing inequities and underrepresentation in gifted education. Educators, community leaders, policymakers and other stakeholders must be proactive and aggressive in making change,” she says.

For years, children from the projects were never selected into Metro Nashville’s ENCORE gifted-and-talented program. Teachers like Tish Smedley changed that and began referring their students, and today several of those students have gone on to college and beyond. Almost two decades later, it’s still not easy. Smedley points to a little boy who is sitting cross-legged on the floor, enrapt in a picture book.

“He’s so bright,” she says. She did some assessments early in the year, but he didn’t test out as gifted because he’d had such little exposure to life experiences. “We’re going to test him again,” she asserts. “I feel confident he’ll be placed in gifted, but we’re going to have to give him some experiences so he’ll do well on the assessments.”

Homemade remedies in the absence of a cure

In the absence of a cure for the achievement gap, a number of programs are being tried in a hit-and-miss attempt to transcend the barriers that gave rise to it. Some of these initiatives have truly affected change.

For example, since 1982, Vanderbilt’s Center for Health Services has served more than 12,000 families through the Maternal Infant Health Outreach Worker, or MIHOW, program. MIHOW is a home-visitation and mother-to-mother mentoring network designed to increase the health and parenting skills of women living below the poverty level, and therefore to close on the preschool achievement gap. MIHOW workers continue to mentor the family until the child reaches age 3.

A strong emphasis is placed on reading after the child is born. Recent data show that 58 percent of 2-year-olds in the MIHOW program are read to daily by a parent or family member, compared to 16 percent of 2-year-olds living below poverty in the U.S.; and 100 percent of MIHOW 2-year-olds are read to at least weekly, compared to 81 percent nationally of 2-year-olds living below poverty. Simply hearing those additional words in their daily background can help these children narrow the gap by the time they’re ready for kindergarten.

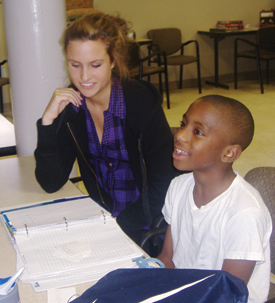

Tish Smedley, pre-K teacher at Ross Elementary in Nashville, sends her students home each summer with a bucket filled with educational supplies and activities in an effort to overcome the “summer dip”.

Meanwhile, inner-city teachers are trying to address the educational imbalance created by the “summer dip.” At the end of each school year, every child finishing pre-K at Ross Elementary receives a “summer bucket.” Tish Smedley and the other pre-K teacher buy sand buckets and fill them with games and activities—color cards, number cards, rhyming cards, letter cards, bubbles, sidewalk chalk, CDs of music they learned in class, and other fun toys for the children to play with over the summer. The teachers pay for these summer buckets largely out of their own pockets. At $15 to $20 per bucket for the 35 children in pre-K, it’s a generous gift. Smedley is not satisfied with how the children have been using the materials in the past, however, so this year she is having a meeting of all parents to show them how to join with their children in the summer bucket activities.

Smedley says, “We’re not saying you have to do everything every day, but just pick one activity every day. And if you don’t do anything else, read to them.”

Some school districts are addressing the summer dip by implementing a year-round school program in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Year-round schools have had uneven results across the country, and there’s no universally effective formula.

Smedley taught in a year-round program for two years until it was canceled. “The teachers were exhausted,” she says. “It was a good program and it kept the gap closed a bit, but we found that the children who needed it the most didn’t come. It started great guns at the beginning of the summer, but then it would dwindle as the summer wore on. My class size dropped from 20 to 13, which wasn’t what Metro wanted. It wasn’t as beneficial as Metro wanted it to be.”

Disparities in health care also reinforce disparities in education. Rothstein’s data indicate that low-income children are absent from school because of illness 30 percent more than middle-income children. “If they’re not in school, they’re not learning,” he says. He believes that equalizing health conditions for children is one of the least expensive ways to move on the gap. He suggests putting full-service health clinics with professional primary care providers on the campuses of low-income schools. This will give students access to preventive health care, such as vaccines and routine medical, dental and vision exams.

In addition to on-site health care, children also need counseling in good nutrition and fitness habits to reach their learning potential, Shields says. One-fourth of American children are either obese or at risk of being obese. “There is more and more evidence that having higher levels of fitness can contribute to your ability to achieve,” she says, adding that in many schools physical education classes are being eliminated to cut costs, “so we’re not making the advances we’d hoped to make on narrowing the gap.”

An underutilized secret weapon

Shields is affiliated with the Community Outreach Partnership Center, a hands-on, collaborative, inner-city advocacy group embarked on a mission of preventing crime, promoting health and enhancing economic opportunities for low-income citizens. In that capacity, she has solicited students from her classes to work with children on the “Veggie Project” and the “Commit to be Fit” nutrition and health programs in underserved neighborhoods.

For three years, Vanderbilt students tutored students in at-risk schools through the Tennessee Academic Civic Engagement Program (TACEP).

Importantly, Shields and Peabody professor Carolyn Hughes have tapped into an underutilized secret weapon in addressing the achievement gap—college students. Vanderbilt University received a three-year grant from Tennessee Academic Civic Engagement Program (TACEP) to establish a mentoring and tutoring program in schools the county deemed most at-risk. Each year, between 250 and 315 Vanderbilt students signed up and fanned out into the neighborhood schools to tutor or mentor between 450 and 625 K-12 students. At the end of the grant, says the program’s director Heather Jolly, TACEP evaluations showed an across-the-boards increase of 30 to 40 percent in grades, graduation rates, college applications and college attendance for students at the participating schools.

In grades K-8, the Vanderbilt mentors emphasized reading, because most of the eighth graders who came for help were barely reading at a third-grade level. Once the mentors worked with them on reading and literacy, the students’ scores improved not only in English, but also in math and science. In the high schools, the mentors assisted students not just with their proficiency requirements so they could graduate, but also helped them develop game plans so they could go to college—a feat many of them had never previously considered. In Tennessee, students need to score at least a 21 on the ACT college prep test to qualify for state scholarship funds. Out of 75 students who were mentored, just a few failed to reach that score.

“Most of these schools have at least 800 to 900 students, and we only saw about 75 students in a school each year,” Jolly says. “But we made a small dent.”

Mentoring gives inner-city children a chance to work with and establish relationships with positive role models. “But this is a reciprocity relationship,” Shields says. “It’s not just about a college student going out and ‘helping’ a student in a low-performing school. It’s also about a college student learning about barriers to achievement and the potential of underachieving youth if they are given possibility, opportunity and tools.”

The directors recruited only those Vanderbilt students who would fully commit to the time demands of the program. “I don’t think this program would have been successful if it weren’t for the trust relationship that the Vanderbilt students established with their mentees,” Jolly reflects. “They met people who wanted them to succeed. So many of these kids, particularly the kids who are struggling, don’t feel like they have anybody who wants them to succeed. Vanderbilt mentors told them, ‘I’m here for you. We’re going to get through this together.'”

Some of those mentees are now in college—adding weight to research that low-income, black students work hardest in response to encouragement. Now that the TACEP mentorship grant has ended, Peabody faculty are searching for ways to keep the program running so they can continue to make a difference in the lives of these students who find themselves on the wrong side of the achievement gap.