Affordable housing. Sexually transmitted disease. School violence and bullying.

It sounds like a laundry list of some of the toughest problems communities encounter today, issues made even more challenging by an economy in turmoil. All are under assault by Peabody faculty actively engaged in research with direct applications to real-world problems.

While there are many examples, three recent projects can be singled out for their focus on empowering community partners with information and technology to jump-start ground-breaking programs:

Susan Saegert, director of the Center for Community Studies, brings her extensive research background in shared-equity home ownership options to a steering committee of community housing leaders working to find new approaches to affordable housing in Nashville.

Velma McBride Murry, who holds the Betts Chair of education and human development, is implementing the first family-oriented, technology-based, culturally sensitive preventive intervention program designed to deter high-risk behavior among youths in six rural West Tennessee counties.

Maury Nation, whose work focuses on violence prevention in schools, is engaged in research to help identify strengths and points of development for at-risk middle schools in Metro Nashville. One of his tasks is develop-ing a strategic plan for each school that empowers educators, administrators, parents, community leaders, businesses and nonprofits to work together to find resources to help those schools become successful.

What stands out is the collaborative nature of these projects, community leaders say. “The great thing about what they’ve done is they’ve said, ‘We’re going to recognize what our strengths are, which is research and analysis, and then turn it over to the people who have experience in implementation,’” says Ted R. Fellman, executive director of the Tennessee Housing Development Agency, part of the steering committee working with Saegert on moderate- to low-income housing options in Nashville.

“That’s what collaboration is all about, and that approach is very well-received,” Fellman says.

Home ownership builds empowerment

When Saegert came to Vanderbilt last year from City University of New York, she found that her colleagues already had laid the groundwork for positive interactions with community partners.

“We have this capacity to work in partnership with different sectors of the community to develop projects, to bring information, and to help them understand national best practices. We can organize information to help them decide how they want to go forward,” Saegert says.

In this case, Saegert was able to apply her extensive research and knowledge of shared-equity housing options to the increasing shortage of affordable housing in Nashville. She and students from her Action Research class studied various shared equity models from around the country and presented several that had the potential for success in Nashville to an informal group looking at affordable housing opportunities in Nashville. The Vanderbilt Legal Clinic provided legal documentation.

The informal group became a steering committee and, through Saegert, connected with the Ford Foundation. Nashville was chosen as one of three pilot cities for a shared equity housing project, still in the early stages of planning.

Paul Johnson of The Housing Fund says Saegert “took it up a notch” in terms of the collaborative nature of the project. Her involvement came at a critical time and accelerated the group’s efforts. She also organized a two-day conference at Vanderbilt to bring stakeholders together.

“There’s lots of traction now about trying to find different housing models that protect consumers better and that give you more accountability when you’re using public funds as a subsidy.”

—Paul Johnson,, director of regional services, The Housing Fund

“There’s lots of traction now about trying to find different housing models that protect consumers better and that give you more accountability when you’re using public funds as a subsidy,” says Johnson, director of regional services.

Through shared-equity, a state or local government agency combines with financial institutions, the housing sector and nonprofits to help provide funding for purchasing a home or unit in a larger complex. The nonprofit agency or a cooperative formed by the agency shares in any value appreciation and provides “more stable stewardship” for monitoring and supporting the homeowners. That share may either be returned to the agency to be used for another family, or it can stay in the dwelling, reducing the cost to the next family.

“All of a sudden the notion of equity sharing seems a little better than just giving people money,” Saegert says, referring to the challenges of the current economy. “It’s no longer such an exotic thought.”

While home ownership has long been viewed as an investment vehicle, low-to moderate-income people are more concerned with security, control and quality than making a profit, Saegert has found. Shared equity allows them to get into a more stable home and improves the possibilities for the next stage of ownership.

Saegert began her academic career in New York City soon after the 1970s disinvestment crisis that left many neighborhoods deeply troubled.

“I was able to be part of a lot of very creative, grass-roots efforts to preserve housing that was inhabited and then abandoned by capital, but not abandoned by residents,” she says. Resident ownership programs that sold buildings to tenants were successful because residents had “more skin in the game.”

“What was really interesting was how the physical environment supported human and social community empowerment,” she says. Saegert clearly revels in engagement in that kind of work—research that is theoretically creative with the practical potential to powerfully and positively impact a community.

Creating positive parenting models

Velma McBride Murry knows firsthand how a tight-knit community can improve a child’s chance of success as an adult. Murry grew up in rural West Tennessee where almost everyone in her small community was related to her, encouraged her, basked in her achievements and stood ready to correct any backsliding. The question driving Murry’s research today is how that sense of responsibility and cohesion can be harnessed to bolster the lives of rural youths, particularly African Americans.

Murry, director of Peabody’s Center for Research on Rural Families and Communities, is the recipient of a five-year, $3.5 million National Institute of Mental Health grant to develop positive parenting models with the ultimate goal to help stem the spread of HIV/AIDS in the rural African American family.

“There’s a nostalgic view that rural families are doing well because of all the fresh air and farmland,” says Murry, professor of human and organizational development. “But rural areas have high poverty rates and families are experiencing a lot of economic challenges.”

In addition, rural youths are engaging in substance and drug use and high-risk sexual behaviors at rates equal to or exceeding those in densely populated inner cities, she says.

“Growing up in environments in which youth are less hopeful of attaining their dreams and life goals may cause youth to cope by using substances and engaging in high-risk sexual behavior as a way of dealing with deprivation,” Murry says. Those challenges are sure to be exacerbated by the current economic downturn, she says.

At the University of Georgia, Murry was part of a research team that for more than a decade conducted basic research to identify families whose children were not at the same level of risk as others. They sought to determine factors that were protective and positive methods of intervention that parents used when destructive behavior occurred. The key, Murry says, was to focus on what worked instead of what didn’t work.

A curriculum was developed focused on promoting, among other things, competent parenting. Eight years after implementation, the UGA researchers found that children exposed to the group program were more likely to delay the onset of sexual activity, less likely to drink or use drugs, and had fewer behavioral or emotional problems in school, Murry says. Not insignificantly, families under the greatest stress benefited the most from the program.

The desire to deliver the program to more people and to those at greatest risk led Murry to return to Tennessee to begin implementation of Pathways for African American Success, which will ultimately involve 525 families in West Tennessee. While the research design is similar to the work in Georgia, the focus is now on removing barriers to access by transferring the psychoeducational program into an interactive DVD program. Initially, the program would be delivered on laptops and then through the Web. The DVD interactive mode will be compared with mailing materials and a group-based program.

The additional layer of technology requires social scientists to interact with software developers—two languages and two schools of thought must be meshed for the program to work, Murry says. Her involvement from the ground up allows deep thought about critical issues, such as making sure nonactors who look and sound like rural African Americans perform the role-playing scenarios in the DVDs.

“We’re excited about doing something that has the potential to make a difference in people’s lives,” she says. The question is whether the technology-driven model, which may have the ability to reach more people, will work as effectively as the group method and become more sustainable.

“This is a new way of delivering a family-based intervention, and we are trying to determine what works best, and which is most cost-effective,” Murry says. “True evidence of a successful community-based program is the extent to which it is sustainable in the community.”

Empowering schools

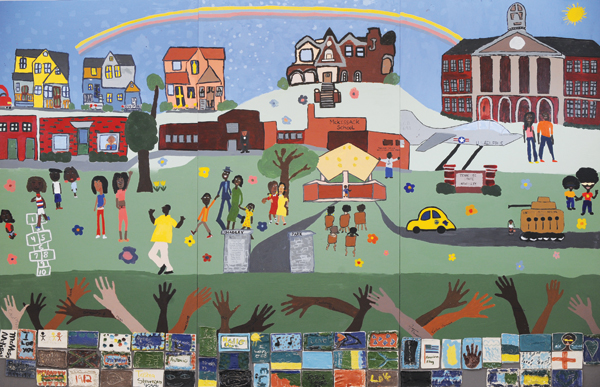

As with his colleagues, engaging community partners is critical to Maury Nation’s recent work in Nashville middle schools through Alignment Nashville. Part of the mayor’s office, Alignment Nashville brings community organizations and resources into alignment to improve school success. Nation’s particular focus is on preventing violence in schools, especially bullying.

Research has shown that bullying leads to long-term problems with aggression for the bullies and other mental health problems for the victims. Creating a positive school environment through violence prevention and positive youth development helps ensure that those children stay in school and have a chance at a quality education, says Nation, assistant professor of human and organizational development.

“Certainly behavior is a component of school success, but we want to see kids do well academically and have productive relationships. That means focusing beyond behavior and looking at the context of the behavior,” he says.

In his CDC-funded research, Nation studies ways to improve the interface between middle schools and community agencies that provide support to students with needs beyond the scope of the school. Through the study, Alignment Nashville coordinators are placed in middle schools and charged with identifying the strengths and points of development for each of the schools. A strategic plan for each school is then developed with input from teachers and administrators with the goal of engaging nonprofit agencies as well as businesses near the schools in working together on improvements.

David Martin, principal at Jere Baxter Middle School, says there’s no shortage of agencies interested in helping schools. The issue is coordinating that help in a way that meets the long-term goals of the school.

Through the Alignment Nashville coordinator at Jere Baxter, “we determine which of those agencies meet our needs as opposed to them coming to us with their agenda,” Martin says.

One of Nation’s roles, in addition to collaborating with the various agencies involved, has been to develop evaluations and program assessments to determine the program’s impact and ultimately create models that can be individualized.

“The needs of each school are pretty distinct depending on where they’re located,” Nation says. Each school has problems as well as points of pride, he says. “We get to recognize and validate those and encourage them to continue to excel.”

One technique that has worked well has been the introduction of an incentive system for children exhibiting positive behaviors (for more information on another positive behavior program, see p. 19). This is especially important for middle school children, Nation says.

Martin says teasing and bullying is common in middle school. It’s a difficult age to reach, yet of critical importance.

Creating a culture of kindness through the work with Nation and Alignment Nashville at Jere Baxter dramatically decreased the number of suspensions and hallway altercations during this academic year, Martin says.

“We used to have fights nonstop,” Martin says. “Now the hallways are quiet and clear, and teaching is going on in the classrooms.”

Nation says he enjoys bringing together community partnerships, but it can be hard to step back and let the main stakeholders direct the outcome.

“Sometimes I take the lead, other times other members of this collaborative take a larger role. It’s been a learning process as an educator to let go,” Nation says. “I feel good that there are times when I thought it should be done a certain way and various stakeholders felt empowered enough to say, ‘No, that doesn’t serve our purpose very well.’ And then we were able to successfully negotiate something of mutual benefit.”

Sydney Rogers, executive director of Alignment Nashville, says she often holds up Nation as an example of an educator who enhances the work of everyone around him. “It’s a win-win for everyone,” she says. “It improves his research, and the schools get the benefit.”

She adds, “He’s one of those people who has the especially helpful ability to move forward our process by being able to see both the research and practical needs clearly.”