The credit crisis and a faltering economy. Rapidly rising energy costs. War. These pressing issues dominate voters’ concerns in advance of the November 4 presidential election. With so many raging fires to fight, the nation seems to have less attention to devote to education policy.

The credit crisis and a faltering economy. Rapidly rising energy costs. War. These pressing issues dominate voters’ concerns in advance of the November 4 presidential election. With so many raging fires to fight, the nation seems to have less attention to devote to education policy.

That does not mean voters do not care about education. In polls that ask them to assess the importance of various issues in their votes for president—as opposed to those more frequent polls that ask respondents to identify only one issue of top concern—education continues to receive high rankings. Polls conducted by Time and CNN over the summer found that more than 80 percent describe education as “extremely important” or “very important” to their votes, putting it on par with health care and terrorism as issues and beating out such hot-button topics as taxes and immigration.

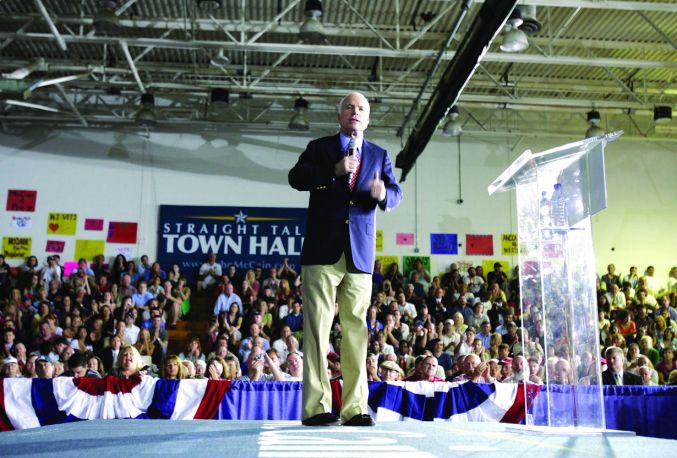

Still, voters continue to identify the economy, energy and national security as the nation’s top priorities, and that is reflected in the presidential campaigns. Senators John McCain and Barack Obama occasionally devote speeches to education reform, but the issue has trouble breaking through the national media fog, even when the candidates frame it as an economic imperative. On September 9, Obama delivered what he intended to be a major speech on education, but most of the coverage centered on his opening comments regarding the now infamous lipstick and pig metaphor.

“Education is periodically an important issue, but it hasn’t been a bread and butter issue, like the economy or defense is now,” says John Geer, Distinguished Professor of political science, public policy and education. Geer’s research specialties include presidential politics, negativity in political advertising and public opinion polling.

“One reason is because a lot of education decisions are made at state and local levels. If you go to a gubernatorial or mayoral election, education is a lot more important,” Geer explains. “Also, think about the candidates’ positions. The way issues play a role is not just about what the public finds important. It’s about the differences between candidates, where they can stake out positions. McCain is looking for an issue where he can catapult ahead. He’s going to choose from the economy or Iraq.

“As for Obama, in the primaries he and Clinton talked a lot about education because they were vying for the support of education groups, which they viewed as critical to getting the nomination. But in the general, teachers unions and groups are going to go for Obama, so he doesn’t have to worry about them as much. As the frontrunner, he’s going to be cautious.”

Geer adds: “Political scientists call education a soft issue. Candidates talk about having ‘the best education in the world.’ Nobody’s against education.”

Looking for a Wedge

In keeping with Geer’s analysis, there are few education policy areas in which Obama and McCain have engaged in direct conflict. They tend to talk about their own ideas without hammering away at each other’s differences. School choice has emerged as an exception to this dynamic.

McCain has made choice—specifically his support for private school voucher programs—central to his educational platform. In a speech to the Urban League in early August, McCain told the audience, speaking of a voucher program in place in Washington, D.C.: “Democrats in Congress, including my opponent, oppose the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship program. In remarks to the American Federation of Teachers last month, Senator Obama dismissed public support for private school vouchers for low-income Americans as, ‘tired rhetoric about vouchers and school choice.’ All of that went over well with the teachers union, but where does it leave families and their children who are stuck in failing schools? … [I]f Senator Obama continues to defer to the teachers unions, instead of committing to real reform, then he should start looking for new slogans.”

McCain describes school choice as a tool to achieve the promise of No Child Left Behind. He proposes expanding the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship program from $13 million to $20 million, and he points approvingly to a new New Orleans voucher program approved in July. He does not explain how a McCain administration would design federal policy to support voucher programs in the states.

Obama opposes voucher programs. He has engaged McCain on choice by emphasizing his support for charter schools, about which McCain has not spoken in detail. In doing this, Obama bucks elements within the Democratic Party and the teachers’ unions who remain skeptical of charter schools.

In a September 9 campaign speech near Dayton, Ohio, Obama outlined a plan for education reform that included doubling federal funding for charter schools, which now stands at approximately $200 million per year.

“Keep in mind that John McCain will say he’s arguing for choice by allowing money and students to drain out of the public schools,” Obama said. “I believe in public schools. But I also believe in fostering competition within the public schools.”

Obama added: “I also know you’ve had a tough time with for-profit charter schools here in Ohio … I’ll work with all our nation’s governors to hold all our charter schools accountable. Charter schools that are successful will get the support they need to grow; charters that aren’t will get shut down.”

NCLB’s choice provisions for children in failing schools have played a big role in increasing interest in charters. Mark Berends, director of Peabody College’s National Center on School Choice and associate professor of public policy and education in the Department of Leadership, Policy and Organizations, sees charter schools as opportunities for educational innovation.

“Under NCLB, so many public schools and districts are moving toward mandated curriculum and pacing guides. Charter schools are not subject to that. They are a lot freer,” Berends says. They also, he notes, greatly vary.

“A big part of what we’re trying to do in our research is understand what works and what doesn’t in charters,” Berends explains. “Not all are effective on achievement. My take is that charter schools can be incubators for finding out what works.”

Voucher programs, Berends says, have received a lot of press, but research has found that if they have an effect, it’s typically a small positive one—though it tends to be greater for African American students. These findings are consistent with research showing positive effects for students attending Catholic schools in urban environments.

As far as Berends is concerned, policymakers need to take a realistic approach that uses choice as a means to an end, not an end in itself.

“I don’t think choice is a panacea–there is no silver bullet–but I also think we should look at innovative ways to use it.”

~ Mark Berends

“If Obama gets elected, I hope there’s allowance for some type of school choice options, such as charter schools,” Berends says. “And I hope that McCain takes a balanced view. I don’t think choice is a panacea—there is no silver bullet—but I also think we should look at innovative ways to use it.”

NCLB Reform and Reauthorization

School choice is just one element being discussed as part of the wider question that looms over the educational landscape: How to reform NCLB? NCLB came up for reauthorization in 2007, but it soon became clear that action would await the next administration.

“There’s going to be modification,” Berends says about NCLB. “They’ll tweak it and revise it. They’re not going to throw it out.” Berends would like to see NCLB accountability measures expanded to include value-added assessment of student progress, as opposed to just proficiency assessment. At the same time, he says, “We have to move beyond a narrow focus on test scores alone.” Berends also supports expanding focus beyond math and reading.

Both McCain and Obama have identified their priorities for NCLB reform. McCain’s focus on choice is not limited to school choice; it is an organizing theme for several proposals regarding tutoring programs and online learning. He also emphasizes giving greater control to school and parental-level agents by distributing funding in ways that bypass federal, state and district bureaucracies.

Obama’s reforms speak more to the issues Berends identifies. Obama calls for new assessment models “that provide educators and students with timely feedback about how to improve student learning; that measure readiness for college and success in an information-age workplace; and that indicate whether individual students are making progress toward reaching high standards. This will include funds for states to implement a broader range of assessments that can evaluate higher-order skills …”

Obama also calls for an “accountability system that supports schools to improve, rather than focuses on punishments,” and he points to a need for English language learner (ELL) and special education appropriate assessments. His plan reads: “Such a system should evaluate continuous progress for students and schools all along the learning continuum and should consider measures beyond reading and math tests. It should also create incentives to keep students in school through graduation, rather than pushing them out to make scores look better.”

Assistant Professor Gilman Whiting teaches at Peabody and serves on the faculty of Vanderbilt’s Program in African American and Diaspora Studies. His research focuses on the achievement gap and on factors that affect minority and low-income boys’ educational behavior.

“When we have high stakes testing, and nothing else matters but the test, no matter how much you push, you end up pushing out a large portion of the population.”

~ Gilman Whiting

“When we have high stakes testing, and nothing else matters but the test, no matter how much you push, you end up pushing out a large portion of the population,” Whiting says, noting that these boys start to disengage in late elementary and middle school. Their disengagement is reflected in the widening of the achievement gap during those years. Then, as Obama’s plan acknowledges, assessment scores bump up in the later high school years when these boys drop out of the system.

Issues that Whiting’s research has identified as important to closing the achievement gap and improving the success of minority and low-income boys are touched upon in the details of Obama’s educational policy. These include Obama’s proposals to target at-risk students in middle school by identifying them early, training school leaders and faculty in the needs of diverse learners and strengthening student support systems. Obama also proposes grants for nonprofit and community-based groups to implement programs proven to help students achieve graduation.

The Three R’s

Recruitment, retention and rewards—these three R’s appear in McCain’s and Obama’s rhetoric on improving K–12 teacher quality. The latter tends to attract the most attention, however, because it raises the controversial issue of performance pay.

A McCain press release from July states: “Funds should also be devoted to provide performance bonuses to teachers who raise student achievement and enhance the school-wide learning environment. Principals may also consider other issues in addition to test scores such as peer evaluations, student subgroup improvements, or being removed from the state’s ‘in need of improvement’ list.”

Obama also advocates merit pay for teachers who make strides in classroom achievement, though he more strongly emphasizes using a wider range of metrics than just test scores. In his September 9 speech in Ohio, Obama told the crowd, “When our teachers succeed in making a real difference in our children’s lives, we should reward them for it by finding new ways to increase teachers’ pay across the board, and to find ways to increase teachers’ pay that are developed with teachers, not imposed on them. We can do this. From Prince George’s County in Maryland to Denver, Colorado, we’re seeing teachers and school boards coming together to design performance pay plans.”

Matt Springer, research assistant professor of public policy and education and director of the National Center on Performance Incentives, in a September interview with NPR’s Larry Abramson said research has yet to prove whether performance pay plans improve student achievement, but he does agree that, without support from teachers, they cannot succeed.

“If you look historically, turbulent times are the best times to advance novel and far-reaching higher ed policy.”

~ Christopher Loss

Higher Ed, Lower Access

NCLB has focused much of the public’s attention on federal K–12 policy. However, until Brown v. Board of Education and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965—of which NCLB is the latest incarnation—federal education policy meant higher ed policy. From the Morrill land grant acts of the 1800s to the Depression-era work-study program, the mid-century GI Bill and the creation of the research infrastructure that underwrites the bulk of our nation’s academic and scientific research, the federal government has played an enormous, transformative role in higher education.

“We tend to think of our higher ed system as being autonomous, decentralized. We never think about the crucial role the government actually plays,” says Christopher Loss, an assistant professor of public policy and education at Peabody, and a specialist in the politics of American higher education. “The GI Bill in 1944 was truly one of the greatest social revolutions in history. Before World War II, higher ed was a pretty exclusive club. In 1939, the enrollment level was about a million and a half. By 1950, it was 2.5 million. By 1948, half of all college students were veterans. The GI Bill changed the socioeconomic mix of students in higher ed and increased the number of students. It opened up opportunity in a very permanent way.”

In tough economic times, especially when college graduates earn so much more than those without college educations, issues of affordability and access come to dominate the higher education landscape. The credit crisis has begun to affect the student loan markets at the same time that a weakening economy is hurting families’ ability to pay for school. Loss says this climate may make it easier for the next administration to tackle tough issues.

“If you look historically, turbulent times are the best times to advance novel and far-reaching higher ed policy,” Loss says. “To the extent you tie higher ed policy to external issues like the economy—and foreign policy, in the case of the GI bill—I think you have a better shot at getting them into law.”

McCain’s campaign has announced general higher education priorities such as simplified tax benefits and aid applications, and an expansion of the government’s direct loan program (“lender of last resort”). Obama has announced detailed proposals on financial aid, community college and college readiness. (See sidebar at left.)

Neither candidate’s campaign has emphasized the more complicated aspects of access such as those studied by Stella Flores, assistant professor of public policy and education at Peabody.

“Right now, I’ve been doing work on how in-state resident tuition policy affects access to immigrants,” Flores says. “Another area of research deals with changes in affirmative action laws across the country.”

Flores says that college access policy, at least in the last 10 years, has been dominated by state-level activity. This, in turn, manifests itself in differentiated access by state. If federal policymakers want to address the persistent low rates of access and college completion among low-income, minority and immigrant students, they will need to understand the differences in state conditions and policies, and the interplay between the two. For example, Flores says, two states with identical merit aid programs may have very different results in terms of minority access, based on levels of segregation within their school systems.

“It’s not one size fits all,” Flores says, talking about the impact of changes to affirmative action policy and the effects of aid mechanisms on diversity. “But we have found that none of the current aid plans get you to the level of diversity the affirmative action plans had.”

McCain has announced his support for a referendum in his home state of Arizona that would amend the state constitution to prohibit preferential treatment or discrimination by state government—including state universities—based on race, sex, ethnicity or national origin. Obama, on the other hand, supports affirmative action in admissions.

Starting at the Beginning

During the Democratic primaries, universal pre-K was one of the beautifully wrapped presents Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton offered voters in a Christmas ad. In the general election, neither candidate offers a universal pre-K plan.

Dale Farran, professor of education and psychology, thinks that’s just as well.

“There are a lot of advocates for universal pre-K, but I would like to see a much more nuanced discussion about it,” says Farran, who specializes in research on preschool curriculum and outcomes. “I think they need to start thinking about the child from zero on up, as opposed to just pushing elementary education down to include pre-K.”

Farran’s research has found that better preschool curricula can help children perform better in elementary school, but there are many variations in settings and in children’s needs. In some areas, children are coming to kindergarten prepared already. She says it’s unclear whether universal pre-K would help them. She also warns that moving all four-year-olds into public school pre-K programs could have consequences for infant and toddler childcare.

“The phrase ‘universal pre-K’ rolls off the tongue much more easily than it is to implement it,” Farran says. “Things are very uneven across the country. You cannot have a universal solution when the problems are not all the same.”

For more complete information on and updates to the education platforms of the two presidential candidates, please see their Web sites.

Obama: www.barackobama.com

McCain: www.johnmccain.com