By Sudipta Chakraborty

Did you ever wonder what made the Mad Hatter from Alice in Wonderland so mad? The phrase “mad as a hatter” actually comes from Mad Hatter disease, better known as mercury poisoning. In the 19th century, fur treated with mercury was used to make felt hats. Hatters were confined in small spaces and breathed toxic mercury fumes, resulting in “mad” or irrational behavior.

Today mercury is used in manufacturing processes, as a vaccine preservative, in dental amalgam fillings, certain medications and cosmetics, and in fluorescent light bulbs. But the most common cause of mercury toxicity in humans results from eating fish and shellfish that have been contaminated by industrial runoff.

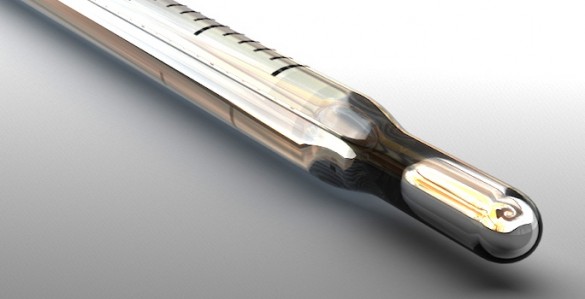

Last month representatives of more than 140 countries agreed to the terms of a treaty called the Minamata Convention that would ban the use of mercury in switches, certain fluorescent lamps, cosmetics, most batteries and certain medical thermometers and blood pressure devices by 2020. The treaty is scheduled to be finalized this fall in Minamata, Japan, where industrial waste poisoned an entire village 50 years ago.

While the treaty is a promising step forward, it does not go far enough, said Michael Aschner, a leading expert on mercury toxicity at Vanderbilt University who had the privilege of meeting patients still suffering from the poisoning in Minamata. In particular, a ban on the use of mercury in some pharmaceuticals “seems to have been tabled,” said Aschner, who directs the Vanderbilt Center in Molecular Toxicology.

The proposed ban also does not cover vaccines containing thimerosal, a mercury-containing preservative. While it declared a “phase-down” of mercury-containing dental amalgams, there is no timeline to phase the dental fillings out completely.

With colleagues at Vanderbilt and around the country, Aschner, the Gray E.B. Stahlman Chair in Neurosciences and professor of Pediatrics and Pharmacology, is investigating links between early-life exposure to mercury and the development of neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease later in life.

These studies, and the final passage and enforcement of the Minamata Convention are essential, because of the continued, serious impact of mercury on human health and the environment. Once in our systems, mercury accumulates in the lungs, kidneys and especially the brain. This can result in a long list of health consequences, including neuropsychiatric problems, kidney dysfunction, muscle weakness, skin and hair issues, and heart problems.

These consequences arise from mercury’s ability to stop the actions of proteins that are vital to proper functioning. This can lead to an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the brain that can then wreak havoc on other necessary proteins in our body. Such neurological damage results can eventually lead to death. As with most toxicants, these effects are magnified in children and pregnant women, making these groups highly sensitive to mercury toxicity.

An unfortunate example of the detrimental consequences associated with toxic mercury emissions comes from Minamata, Japan. In the 1950s and 1960s, a new chemical company dumped its wastewater into Minamata Bay, resulting in the toxic accumulation of mercury in the town’s water supply.

Consequently, the local population became poisoned by methylmercury following consumption of shellfish and fish from the bay that had high mercury content due to bioaccumulation, and developed what became known as Minamata disease. Many of the victims died from the poisoning, after developing symptoms that included severe muscle weakness, ataxia, and hearing and vision problems.

The toxicant also transferred from the mother’s bloodstream to the fetus in the womb. This resulted in the births of several children with cerebral palsy and other deformities in the 1960s. These patients are now in their 40s and 50s, with some still requiring care in either hospitals or other resident support facilities.

In light of the Minamata Bay incident and others around the world, the scientific community has urged opened discussions on how to reduce both man-made and environmental mercury emissions. As fish and shellfish are widely consumed by the population, new advisories have been posted on the amount and type of fish that should be consumed in a week.

However, mercury is still heavily present in the environment due to its abundant role in man-made manufacturing processes. In fact, the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) recently reported that the top 100 meters of ocean water contain nearly twice the mercury that was reported a century ago, with deeper waters having 10-25 percent more.

This slow movement of the heavy metal through water further illustrates the need for more immediate and firmer regulations to remove mercury from their current sources. Even if such regulations were implemented today, it would take several years for current emissions to be removed from the environment.

While not perfect, the hope is that the Minamata Convention will raise awareness about the dangers of environmental mercury exposure and lead to growing pressure to reduce pharmaceutical as well as industrial “emissions” of the heavy metal. After all, the world is already a beautiful, but mad place – we certainly don’t need any more mad hatters around.