Archaeological sites that currently take years to map will be completed in hours if tests underway in Peru of a new system being developed at Vanderbilt University go well.

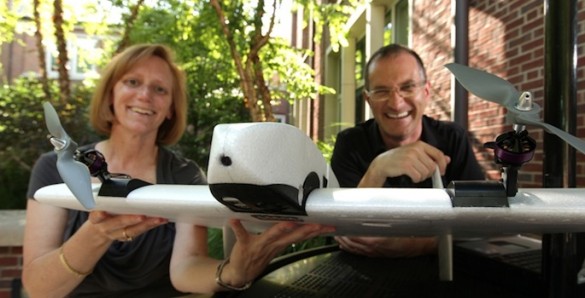

The Aurora Flight Sciences Skate Small Unmanned Aerial System will be integrated into a larger system framework that combines a flying device that can fit into a backpack with new and existing software that can discern an optimal flight pattern, transform the resulting images into a single image and then transform the single image into a three-dimensional map. The project is an interdisciplinary collaboration between Vanderbilt archaeologist Steven Wernke and engineering professor Julie A. Adams.

The project is primarily financed by an Interdisciplinary Discovery Grant from Vanderbilt, with some support from the National Science Foundation.

“It can take two or three years to map one site in two dimensions,” Wernke said. “This should transform how we map large sites that take several seasons to document using traditional methods. It will provide much higher resolution imagery than even the best satellite imagery, and it will produce a detailed three-dimensional model.”

The gear is compact and designed to be easy to use.

“You will unpack it, specify the area that you need it to cover and then launch it,” Wernke said. “When it completes capturing the images, it lands and the images are downloaded, matched into a large mosaic, and transformed into a map.”

The algorithms developed for the project allow it to specify the flight pattern to compensate for factors such as the wind speed, the angle of the sun and photographic details like image overlap and image resolution, Adams said.

“The only way for this method to be cost effective is for it to be easy enough to operate that you don’t need an engineer on every site,” Adams said. “It has to be useable without on-site technical help.”

Tests are scheduled from mid-July to mid-August at the abandoned colonial era town of Mawchu Llacta in Peru, and plans call to return next year after any issues that arise are addressed in the lab.

Built in the 1570s at a former Inca settlement and abandoned in the 19th century, the village of Mawchu Llacta is a 45-minute hike for the team from the nearby village of Tuti. Mawchu Llacta is composed of standing architecture arranged in regular blocks covering about 25 football fields square.

“Archaeology is a spatial discipline,” Wernke said, “we depend on accurate documentation of not just what artifacts were used in a given time period, but how they were used in their cultural context. In this sense, this method can provide a fundamental toolset of wide significance in archaeological research.”

Wernke hopes that the new technology will allow many archaeological sites to be catalogued very quickly, since many are being wiped away by development and time.

“This should be a way to create a digital archival registry of archaeological sites before it’s too late,” he said. “It will likely create the far more positive problem of having so much data that it will take some time go through it all properly.”

The method could also have other applications, including the tracking of the progress of global warming and as a tool for first-responders at disaster sites.

“The device would be an excellent tool for evaluating the site of a major crisis such as Sept. 11 to decide how to deploy lifesaving resources more effectively,” Adams said.