Visual Arts

At first glance, the basement of Sylvia Hyman’s home looks much like any other clay artist’s studio. A shelf running along the wall holds jar after jar of oxides, silicates, fluxes and other materials used in the preparation of ceramic glazes. A large kiln sits in one corner, and two long work tables stand in the middle of the room. One of the tables holds a seemingly random stack of books: an art history volume, a suspense novel titled Danger Music, a copy of Dr. Seuss’ The Cat in the Hat. A crossword puzzle book sits nearby, on a neatly arranged breakfast tray.

Peer more closely, though, and you’ll do a double take: These aren’t books at all. They are made entirely from clay.

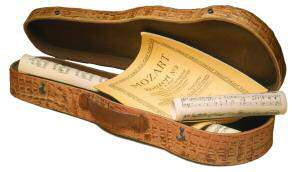

The art of Sylvia Hyman,MA’63–masterful trompe l’oeil sculptures–uncannily mimics objects from real life.Whether taking the form of books, boxes, baskets, printed scrolls, letters or playing cards, each piece skillfully deceives the eye.

To succeed as art, trompe l’oeil painting and sculpture must do more than simply replicate an object or scene. In Hyman’s case, her ceramic works convey playfulness and joy, mixed with sly consideration. For her these sculptures operate on a number of levels, but one central conceit is the idea of communication.

“My first ceramic trompe l’oeil works were done for fun,” she explains.

“In the 1960s I made dancing banana skins and partially eaten fruits on brightly colored, glazed plates. Then in the 1980s I made some porcelain birthday cakes, fortune cookies and cantaloupes for gag gifts. The more serious works that began in the ’90s–expanding on the idea that fortune cookies carry concealed information–started with scrolls that imitated diplomas and certificates.

“Now my work has grown to encompass the myriad ways that humans communicate, not only through language, but also with signs and symbols such as musical notes, maps, drawings, diagrams and puzzles. I’m enthralled by the way that humans, through the centuries, have devised ways to convey thoughts by making marks on stone, papyrus, clay, paper, etc.”

For Hyman, achieving precision and detail in her works is the result of a constant learning process. “Almost every piece I make involves trial and error. Sometimes I have to remake parts of a sculpture or even rethink the whole arrangement of the various parts as my works become more complex.”

Hyman’s art was the subject of an exhibit at Nashville’s Frist Center for the Visual Arts, which ran through Oct. 7.

Hyman turns 90 this year, and the Frist show was only the most recent honor in an energetic career that has seen her work travel the globe, with exhibitions on three continents. Her ceramic pieces sit in the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, and nearly a dozen other institutions.

“Sylvia has kept herself young and engaged in the world of art in a way that transcends generations,” says independent curator and arts writer Susan Knowles, BA’74, MLS’75, MA’86.

“She has been a great role model for other artists here because she stands up for herself as an artist, she’s interested in what’s happening creatively in Nashville, and she’s willing to give her time to things she feels are important. She has a real sense of justice and fair play.”

(A longer version of this article was originally published July 15, 2007, in The Tennessean.)