Media Inquiries

- 615-322-6397 Email

Latest Stories

- David Cortez wins Protein Society award for contributions to basic protein science

- Vanderbilt University, University of Cambridge, King’s College Cambridge, White House, and United Kingdom’s Government Communications Headquarters to convene and discuss critical issues pertaining to post-quantum cryptography

- WATCH: Collaboration creates inspiration for Class of 2024 students

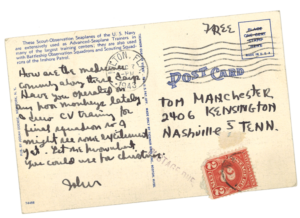

When John Speier Manchester left Vanderbilt halfway through his sophomore year in December 1942 to enlist in the U.S. Navy, he was eager to make his name as a dashing World War II fighter pilot. A little more than a month after joining, the fresh-faced 19-year-old son of former Vanderbilt professor Paul T. Manchester, MA’21, PhD’27, found himself trundling along in a Pullman car headed to Columbia, South Carolina, for his first training assignment.

It was the start of a nearly two-year journey that ended after Manchester was shot down in a Helldiver bombing raid over Manila Bay in November 1944, less than a week after learning his maternal grandfather had died. Through it all, Manchester wrote 197 letters back home, which his sister, Emily Manchester Townes, BA’50, compiled into a family history called School Boy to Helldiver. She recently shared the collection with Vanderbilt Magazine.

The letters excerpted here show the trajectory Manchester followed, “from a college sophomore to a World War II warrior,” as Townes writes. They also offer an intimate view of the war’s impact on the soldiers themselves, as well as on the family members left behind on the home front.

Note: Text of the letters has been edited sparingly for grammar and style.

Jan. 21, 1943

Columbia, South Carolina

Dear Folks,

Since I haven’t much time before going to bed, I will write only one letter to you all. Let Grandma see it and explain that my time is very limited.

The trip up here was the hardest thing of all. I got into Atlanta at 1:30 a.m. I ate breakfast with the Cochrans and got here at about 8:30.

The commanding officer is a swell fellow. He showed us our rooms, where we report in the morning, and excused us from military gym tomorrow morning. Therefore we won’t have to get up until 7:30 (0730 Navy time).

…

We bunk in a private home about a block from the university. There are four of us boys in two nice cozy rooms. One’s from Memphis and the other from Pensacola. It’s like being a civilian, only we get snappy uniforms and are under strict personal discipline. The reason we are put up in these civilian houses is that the dormitories are already filled up with Army cadets.

My love to everybody,

Johnny

Jan. 23, 1943

Columbia, South Carolina

Dear Tom [John’s brother, Dr. Paul Thomas Manchester, BA’43, MD’45],

I’m just getting settled into a life of limited sleep and unlimited study. From 0545 (5:45 a.m.) to 2200 (10 p.m.) we exercise, study, fly, eat and study some more.

…

We spend eight hours of the day at Owens Flying Field, where we are instructed in the flight of Piper Cubs of the 65 h.p. class. I went up for the first time today. What a thrill it was when I put my parachute on—insurance regulations demand that cadets wear parachutes on all flights—and climbed into the cockpit behind my instructor. The instructor being out of the plane (on the ground) speaks first always. He will say “switch off.” I say “switch off.” He then gives the propeller a few twists to draw gasoline (which is 91 octane) into the carburetor. He then says “switch on,” “contact.” When he says this, I push the magneto switches on and say “contact.” He cranks the propeller once, and the engine catches. You would be surprised at the great number of things which must be checked before a plane leaves the ground.

…

We solo after six to eight hours of dual instruction. I’ll write you all before I solo. I really have little time for writing, but I’ll write as often as circumstances permit.

Love and kisses (to Miss Vanderbilt),

John

March 12, 1943

Owens Field, South Carolina

Dear Grandpa,

I got a nice letter from Grandma in which she told me all the news from home. She said that you were feeling pretty bad. I hope you are better when I get home, which I think will be pretty soon.

I am enclosing a picture of me and my bunk-mate. I have on one of the woolen flying helmets they gave us, which feel mighty good when you are high above the clouds. I went up 5,300 feet high yesterday which is against the rules. We aren’t supposed to go over 3,500 feet when by ourselves. I hid in the clouds and then made a seven-turn tailspin in which I lost 1,400 feet of altitude. I was so dizzy when I came out of it, I thought for a moment I was going to pass out. Now the boys call me “Mile-High Manchester.”

Love to all,

John

May 14, 1943

U.S. Navy Pre-Flight School

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Dear Grandpa and Grandma,

I’m mighty tired out about this time of night, 2045 (8:45 p.m.). We generally fall asleep before taps. When they blow the bugle telling us to go to sleep, it wakes us up instead.

…

I’m getting some mighty good training up here, and I will never regret joining up. It will make me a better man for the future life I have to lead.

Ted Williams, pro baseball’s greatest for 1942, is in my company. Everybody tries to get his autograph. He really is a good feller.

I hope you are feeling better now and are taking advantage of that nice spring weather you’re having down in Nashville.

You’re going to see a different Johnny come home: “rough, tough, and smart.” That’s our motto up here.

Love,

Johnny

July 29, 1943

U.S. Naval Reserve Aviation Base

Peru, Indiana

Dear Mother,

This place really beats Chapel Hill in every respect. The food is wonderful—cooked splendidly and plenty of it. The bunks are soft as cotton and there’s a cool breeze every night.

We will start flying Sunday. They have about 350 Stearman N2S trainers up here, and before we leave here, we will be experts in acrobatics, formation and night flying, and navigation. There are about 700 cadets up here and the course lasts 11 weeks.

…

I’m awful sorry I couldn’t come home last week, but my progress comes first. There will be plenty of time after the war for me to loaf around and tell my big tales of flying and fighting.

All my love to everybody,

Son John

Dec. 1, 1943

U.S. Naval Air Training Center

Pensacola, Florida

Dear Mom,

Today I have been in a year. Do you remember the day Reavill [Ransom, son of acclaimed poet, literary critic and Vanderbilt English professor John Crowe Ransom, BA 1909] and I went down to Atlanta and were sworn in? I thought it would be a lot of fun. And it has been—along with the hard work and disappointments.

…

I am flying a “North American [T-6] Texan” advanced trainer with 650 horses and all sorts of gadgets. This is the hardest phase of the whole setup, and it will take no small amount of work to pull me through the next two weeks and a half.

I room with three other boys whose hometowns are scattered all over the U.S. One from Ohio, one from Idaho, and one from Mass. All good boys.

I’m getting sleepy,

John

Jan. 21, 1944

U.S. Naval Air Training Center

Pensacola, Florida

Dear Tom,

I had my first flight at Barin [Field] this morning, a two-hour dual and a one-hour solo. We flew out of Silver Hill field for some landing practice, and along with about five other planes, we shot landings for a while. Then we taxied over on the grass, put the parking brakes on and got out. We watered the lilies and smoked a cigarette with the other instructors and cadets. The sun was hot and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky, so we were rather warm in our winter flight gear. One plane buzzed us and blew sand in our eyes as we told dirty jokes. It was the first touch of spring, and I hope it lasts.

Then I took off, and for the first time since I began my training—I had a plane with retractable landing gear! We went up to 5,000 and did some slow rolls and spins to demonstrate the characteristics of the plane to me. The next period I went up alone and with a feeling of accomplishment—I was happy. My radio went fluckey, so I had to go on without it.

But you have me beat. Your future is promising, and I know how proud the folks are of you. I think Momma wanted me to be a doctor, but I haven’t the temperament for it. I have made up my mind—when the war is over, I’m going back to school and take up law.

We have a radio in the room now and are listening to the All Time Hit Parade now. It’s amazing what music can do to a person, especially one away from home.

…

I’m no sentimentalist or dreamer—the Lord knows I am rarely in the state of thought—but I was just thinking how swell our folks are. Pop would give you anything he had, and Momma has always taken care of us. I only hope I can make them proud of me. I know you have lived up to all their hopes. It takes a lot of study to learn all those bones and organs of the body. If you have any good cases of [obstetrics] (or something like that)—DO YOUR BEST! Egad, to think you can bring kids into this world!

Your Brother,

Johnny

Aug. 12, 1944

Wildwood, New Jersey

Dear Daddy,

I leave for Norfolk tomorrow to join Bombing Squadron 80, which will leave the continental limits in about three weeks. The ship is the USS Ticonderoga new Essex-class carrier, and first stop will be Pearl Harbor. We will probably stay there a few weeks, then into a task force and a little action. Most squadrons come back after six months in the S. Pacific, so I will probably return sometime in March or April ’45.

…

It might have been a crazy idea to volunteer for such a mission, but I have my own reasons for wanting action.

…

Please don’t condemn me for volunteering, but try to understand how anxious I am to see the place I have heard so much about.

I’m in the big time now—two N.Y. debs gave Dugan and me a going away party last night. The one that escorted me (or rather stayed with me) was No. 1 deb in N.Y. in ’44. Or maybe they just felt sorry for us.

More later,

Your son John

Oct. 1, 1944

South Pacific

Dear Uncle Harry,

I was very glad to hear from you as we get mail very seldom, and when we do I seldom get any anyway.

…

You know, Uncle Henry, even though I am seeing places you never heard of and flying a dive bomber in the toughest competitions possible, I still feel like a kid. And if I ever hear you say that you and Dad are puny again, I’ll wallop the hell out of you. All the excitement may be pretty glamorous, but it’s you fellers that have the brains. And if I can be half the success you are—I will be entirely satisfied.

I’m getting hardened. All the night flying and scares have taken my youth away. We live from day to day, and hopes of getting to the States again are never voiced. I hear Bud Manchester got the Distinguished Flying Cross for bringing his damaged plane and wounded crew back safely. I can’t promise that much, but I will sure as shooting drop some TNT on the Japanese Navy, and soon.

Well, I don’t feel like writing tonight, and anything that I put in here would probably be cut out by the censor—so I’ll close here—

I’m sleepy.

My love to all the family,

John

Nov. 7, 1944

South Pacific

Dear Mother,

We received mail for the first time in three weeks this morning. I got seven letters from you and the others, including the news of Grandpa’s passing. Of course I don’t know how hard everybody took it, but I haven’t too much time to cry. I think Grandpa was one of the most-liked men in Nashville, and much of my manner and speech is his. I grieve at our loss and extend whatever comfort I can to all the family. To Grandmother, my everlasting love and affection and hope that she might find strength in the near future. I will be home soon to take care of everybody.

…

If you don’t hear from me for great lengths of time—never fear. I will come back after I have finished my job. This time here, the following, the near past, are the most momentous of my life. Believe me when I say that those around me and I, we are shaping the future. It is terrific.

Love to you mother,

Your second son, John S.

Nov. 8, 1944

South Pacific

Dear Grandma,

I received word yesterday of our great loss in Grandpa’s death. I am far away and can’t be with you at this sad time, but know in your heart that my sympathies are with you.

I am counting on you, Grandma, to take it easy and come through with spirit. You can start anew and with your limitless strength carry on in happiness. I want to stay with you when I return home and live as we need to, all one big happy family.

The sea is rough today, and our own great ship heaves and tosses in its fury. Huge waves pound its hull, and we stumble around trying to stand up. Rain pours in torrents, and the wind howls through the portholes.

But tomorrow will be sunny, and the sea gulls and flying fish shall fly around in the cool breeze. I shall fly tomorrow and soar into the heavens in search of enemy craft.

Let it be the same with you. Trust in the future and never give up hope. God will look out for us. Both peace and love shall be with us soon.

I shall be home next spring, and we will all go out to LaVergne and have chicken and biscuits. I am very proud of my brother and little sister; they are great successes.

I retain my middle name, Speier, and with it I can never go wrong. Soon I will have finished my job and shall be home with you. I am expecting to see you younger and stronger when I arrive.

Don’t let me down.

Love from,

John Speier Manchester

Nov. 10, 1944

South Pacific

Dear Mother,

It’s time you heard from me. With the violent shock of Grandpa’s death and winter coming along, I think you need some warmth for

your heart.

My plane is now officially known as “Speier’s Flyer.” The skipper asked me why I chose such a name, and all I could say was, “It’s an old family name, sir.” Let us say that I am the first real aviator in the Speier family and that I should rightly be called the Speier Flyer. I seem to embody quite a few firsts. First Navy man, first pilot, first to go West and, most of all, the first son to leave you.

…

Censorship forbids mention of places and action, but—well, I’ll tell you about it when I return.

Keep the fireplace warm and plenty of stuff in the refrigerator for me. I have enough medals now to warrant a real bouquet. Everybody gets them out here.

Keep strong,

John

Nov. 18, 1944

South Pacific

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Manchester,

This is a letter which I had hoped would never have to be written. It has now been six days since the action took place in which John has been reported missing. It all seems unreal yet, as if he has just gone on a short trip. By the time this letter arrives, you will have received the Navy notice which reports John as missing. I shall try and tell you everything I know of the circumstances.

Due to military secrecy I cannot tell you the location of the target. We made two strikes against it on the 12th, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. I was on the first strike, but not the second. It was on the second strike that John was lost. The anti-aircraft fire was exceedingly intense, and John’s plane was observed by Ensign Raby to have been hit at 9,000 feet as he had just entered his dive. The plane burst into flames and fell off into a spin. No parachutes were seen to emerge from the burning plane.

Judging from the nature of the explosion, the loss of control, and the fact that no parachute emerged from the plane when there was sufficient time to escape, it is a certainty that both men were killed instantly by the exploding shell.

…

In the past two months, we two had become very close, and I now can’t seem to bring myself to the reality of the loss. He is in my daily prayers and thoughts and is remembered each day by Father O’Brien at daily mass.

Once again and always,

my sympathy and prayers,

Dugan Doyle