Waiting to Exhale

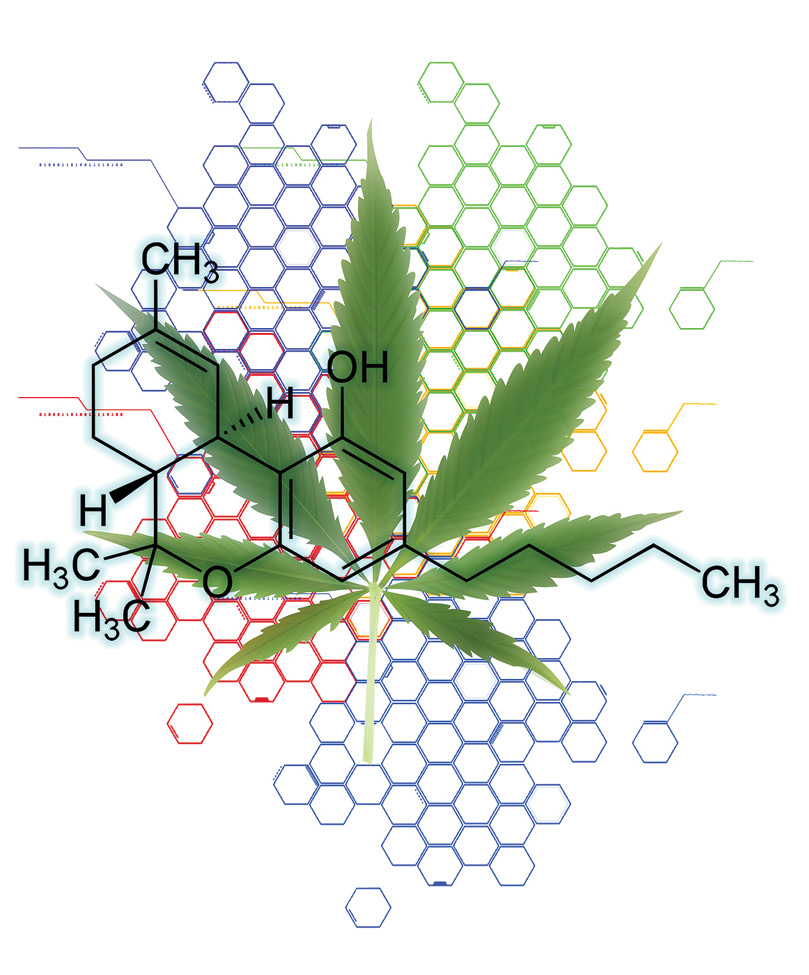

An international group led by Vanderbilt researchers has found cannabinoid receptors, through which marijuana exerts its effects, in a key emotional hub in the brain involved in regulating anxiety and the fight-or-flight response.

This is the first time cannabinoid receptors have been identified in the central nucleus of the amygdala in a mouse model, they report in the March issue of the journal Neuron. The discovery may help explain why marijuana users say they take the drug mainly to reduce anxiety, says Dr. Sachin Patel, the paper’s senior author and an assistant professor of psychiatry, molecular physiology and biophysics.

Led by first author Teniel Ramikie, a graduate student in Patel’s lab, researchers showed for the first time how nerve cells in this part of the brain make and release their own natural “endocannabinoids.” They used high-affinity antibodies to “label” cannabinoid receptors so they could be seen using various microscopy techniques, including electron microscopy, which allows very detailed visualization at individual synapses, or gaps between nerve cells.

“We know where the receptors are, we know their function, we know how these neurons make their own cannabinoids,” says Patel. “Now can we see how that system is affected by … stress and chronic [marijuana] use? It might fundamentally change our understanding of cellular communication in the amygdala.”

The research team included scientists from Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest, and Indiana University in Bloomington.

Income Inequality Is Making Americans Sick

Income inequality and other economic and social factors are making Americans sick, according to a groundbreaking article by Dr. Jonathan Metzl and Dr. Helena Hansen. Traditionally, U.S. physicians are trained to diagnose patients’ illnesses through attention to biological systems. But Metzl, the Frederick B. Rentschler II Professor of Sociology and Medicine, Health and Society, and Hansen, a professor of psychiatry and anthropology at New York University, contend that training in biology alone leaves doctors woefully unprepared for understanding how people’s health is determined as much by their ZIP codes as their genetic codes.

Writing in the February issue of Social Science and Medicine, Metzl and Hansen introduce a five-step way of training physicians based on a method called “structural competency.” Structural competency teaches doctors to better recognize how medical issues like hypertension, depression and obesity sometimes represent the downstream effects of societal decisions about such factors as food distribution networks, transit systems, or urban or rural infrastructure. And it promotes societal engagement “beyond the walls of the clinic” by the medical profession. They contend that doctors should be trained to better recognize the ways in which social and economic forces produce illness, and that helping people “medically” must sometimes also involve improving their lives economically and socially.

Metzl coined the term “structural competency” in his book The Protest Psychosis as an expansion of the “cultural competency” concept that caregivers have struggled with for decades. Structural competency has since become the theme of several conferences at medical centers throughout the United States.

Cancer, Microbes and Evolutionary Mismatch

Why do people of mostly Amerindian ancestry in the Andes have a gastric cancer rate 25 times higher than that of fellow Colombians of mostly African descent only 124 miles away on the coast? The answer is disruption of co-evolution of the humans and Helicobacter pylori, the bacterium that infects their stomach lining and is the leading cause of gastric cancer throughout the world.

In a report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Barbara Schneider, research professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, and colleagues conclude that the interaction between host and pathogen ancestries completely accounts for the difference in the severity of gastric lesions in two regions of the same country. An evolutionary mismatch between human and microbe is the reason for this difference.

Understanding the role of co-evolutionary relationships in gastric disease may inform prevention efforts to eradicate H. pylori infection in those at greatest risk, the researchers conclude.

Lullabies for Preemies

Premature babies who receive an interventional therapy combining their mothers’ voices and a pacifier-activated music player learn to eat more efficiently and have their feeding tubes removed sooner than other preemies, according to a Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt study published online Feb. 17 in Pediatrics.

The randomized clinical trial performed in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Children’s Hospital tested 94 premature babies, pairing their mothers’ voices singing a lullaby with pacifier-activated music players. Participating babies received the intervention for 15 minutes a day for five days in a row. When they sucked correctly on the pacifier, a special device with sensors and speakers, they were rewarded by hearing their mothers singing a lullaby. If they stopped sucking, the music would stop.

“A mother’s voice is a powerful auditory cue,” says study author Dr. Nathalie Maitre, assistant professor of pediatrics, physical medicine and rehabilitation. “Babies know and love their mother’s voice. It has proven to be the perfect incentive to help motivate these babies.”

Watch a video about the study: