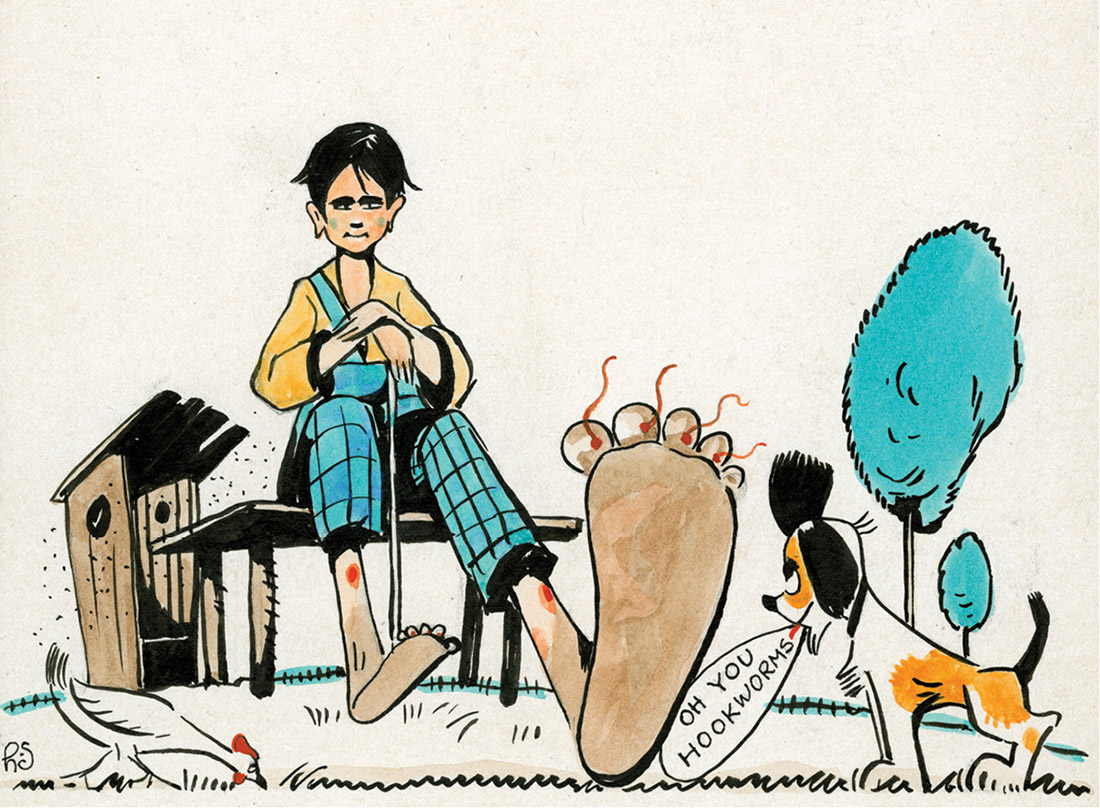

In the fall of 1902, Dr. Charles Wardell Stiles, a zoologist with the U.S. Public Health Service, got a hunch that parasites were causing large swaths of the South’s rural poor to suffer an array of debilitating symptoms: stunted growth, anemia, bloated stomachs, even a disconcerting habit of eating dirt. Hoping to prove his theory, Dr. Stiles embarked on a tour of the region, collecting stool samples everywhere he went (gross, I know). As he suspected, hookworms were rampant. Fortunately, those infected could be cured with a cheap combination of thymol and Epsom salts.

When Stiles shared his findings—and easy solution—with the East Coast medical establishment, he wasn’t lauded as a hero, but derided as a fool. Hookworms aren’t causing widespread lethargy throughout the South, the thinking went. Hillbillies are just naturally stupid and lazy!

It wasn’t until 1908, when Stiles casually mentioned his hookworm findings to a colleague who worked closely with the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, that he got a sympathetic hearing. Soon after that conversation, he was summoned to New York to present his case.

By 1910 the Rockefeller philanthropy committed $1 million (about $25 million today) to eradicate hookworm from the American South. Wickliffe Rose, a professor and former dean of Peabody College, organized and led the effort as executive secretary of the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease. It quickly became apparent that the hookworm problem was even more widespread than previously thought, with about 7.5 million people affected, including 40 percent of all school-aged children. Deploying mobile dispensaries and launching an intensive education campaign, hookworm was mostly eliminated from the region by the end of 1914. Rose would go on to become the first director of the International Health Board and receive the Public Welfare Medal in 1931.

Today the effort to eradicate hookworm is still being celebrated as a breakthrough in both public health policy and philanthropy.

I am reminded of this story because it highlights three important themes in this issue of Vanderbilt Magazine. First is the transformative power of philanthropy. Unlike a traditional business, which expects a direct return on investment, philanthropy is akin to planting seeds and hoping that wonderful things grow. Vanderbilt Board of Trust member Dr. Robert Schiff Jr., BS’77, talks about his recent $10 million gift to fund scholarships for Opportunity Vanderbilt, and why giving back has always been important in his family.

Second is the multilayered approach to public health the anti-hookworm effort represented. It wasn’t enough to simply identify and cure those who were infected. Education was also critical to prevent future outbreaks. A century later Vanderbilt continues to strengthen its role in health policy under the leadership of Melinda Buntin, former deputy assistant director for health at the Congressional Budget Office.

Third, and perhaps most important, is simply the reminder to challenge stereotypes. In a similar way that poor residents in the South were laughed off by medical experts of the era, women and minorities traditionally have been left behind in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) education. But Vanderbilt postdoctoral researcher Jedidah Isler, one of the earliest students in the Fisk–Vanderbilt Bridge program and the first black woman to receive a doctorate from Yale’s astronomy department, is working hard to change that, all while hitting the TED lecture circuit and breaking new ground in her own research.

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the horrific tragedies that hit the Vanderbilt community in March. Taylor Force, a West Point graduate and first-year MBA student, was killed by a terrorist while on a school trip to Israel exploring global entrepreneurship. Unfathomably, two weeks later, a bomb ripped through the Brussels airport, claiming the lives of Justin Shults, BA’08, MAcc’09, and his wife, Stephanie, MAcc’09. To echo the sentiments of Chancellor Nicholas S. Zeppos, our hearts simply ache for these members of the Vanderbilt family that we lost.