By Andrew Maraniss, BA’92

For Perry Wallace, it was never about him.

Every time the spotlight shone on the sports and civil rights pioneer, he used the platform to advocate for others.

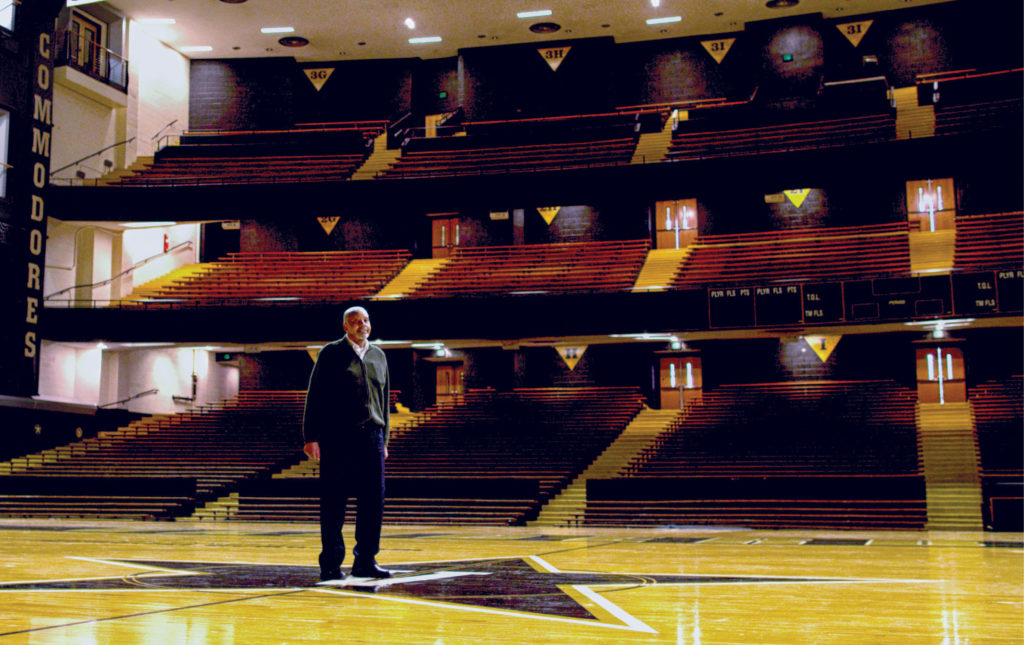

A law professor at American University who was the first African American varsity basketball player in the SEC, Wallace died Dec. 1, 2017, in Rockville, Maryland. Two weeks earlier, Vanderbilt Vice Chancellor and Athletics Director David Williams II, Deputy Athletics Director Candice Lee, BS’00, MEd’02, EdD’12, and I flew up from Nashville to visit him one last time.

Although his bedridden 6-foot-5 frame seemed smaller, his hair was gone, and his skin was pale, in other respects Wallace was the same as ever. He still raised his index finger to make a point. He still had his deadpan sense of humor. He still made everyone else feel at ease. And he issued a challenge to us to work on behalf of others.

Wallace, who was 69, spoke about the influence of his mother, Hattie, a brilliant woman who, because of racism and poverty, attended school only through the eighth grade in rural Tennessee. Wallace told us about one of his favorite photographs, one in which his mother sat in a windowsill, reading a book by the light of the sun. She may not have had as much formal schooling as she desired, but Hattie Wallace was a lifelong learner, and she took enormous pride in the achievements of her children. On her income as a cleaning lady and that of her husband, Perry Sr., as a brick cleaner, the couple sent their four daughters to college at Tennessee State and Fisk universities. Brother James joined the Air Force, and Perry enrolled at hometown Vanderbilt in the fall of 1966, a member of just the third class of black undergraduates at the school.

As he looked Williams, Lee and me in the eye and invoked the limitations imposed on his mother, Wallace asked that in his memory, and hers, we seek to create greater opportunities for women. Everyone must have the chance to make their contribution to society, he said through tears.

Wallace advocated on behalf of other vulnerable citizens throughout his life. As an attorney he wrote about the forgotten victims of environmental racism. He traveled to Nigeria with a team of international lawyers to represent a young, unwed woman sentenced to death for the “crime” of having been impregnated by an abuser. He saw children as a reminder of the promise of humanity, even when adults around him so often showed its worst aspects.

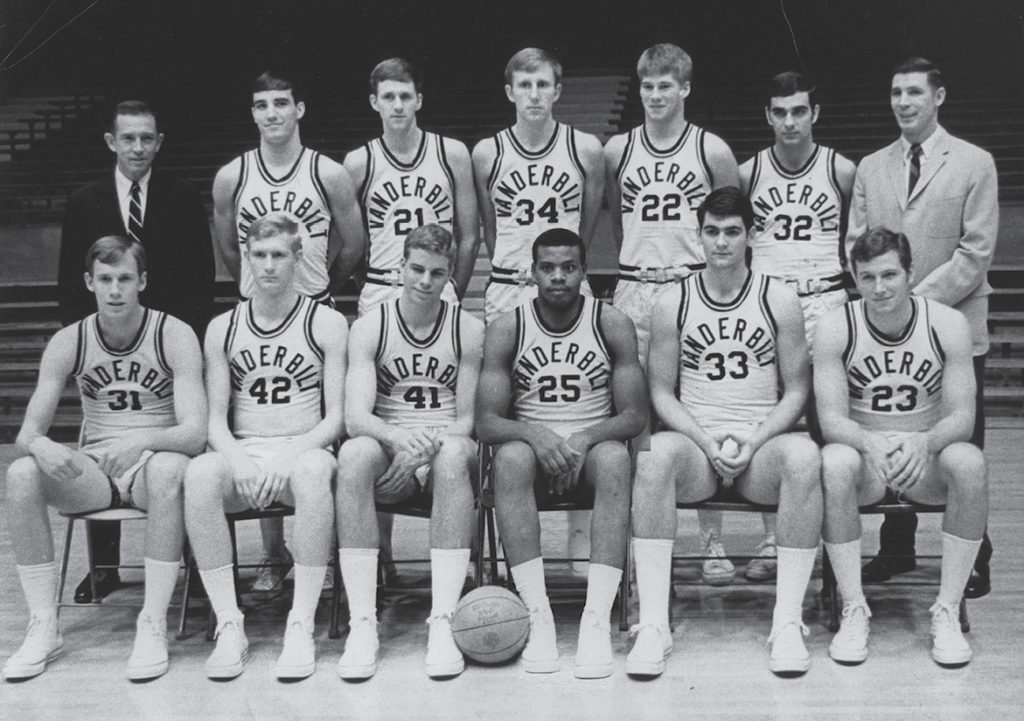

When word got out in Nashville in the mid-’60s that Vanderbilt was recruiting him, some fans sent petitions to Coach Roy Skinner, MA’58, in protest; others sent death threats to Wallace’s home. In the late fall of 1966, when the University of Mississippi realized the Vanderbilt freshman team had two black players, it canceled both of its upcoming games against the Commodores. The following year, when Wallace traveled to Oxford as a member of the Vanderbilt varsity team, Ole Miss fans stood and cheered when he was bloodied by an intentional elbow to the face.

Before road trips to the small Southern college towns of the SEC, Wallace would imagine the worst thing that could happen; in his mind, he could be shot and killed, either on the court or around town before or after a game. After he gave an honest interview to The Tennessean in Nashville the day after his final game in 1970, describing the loneliness and isolation he felt on his own campus, Wallace was essentially driven out of town by angry fans who canceled their subscriptions to the paper, calling him “ungrateful.”

When Wallace encountered vicious catcalls and threats on his first road trip to Starkville, Mississippi, as a freshman, his sister Jessie begged their father to take him out of Vanderbilt. Perry Sr. resisted, saying his son had set his hands to the plow and could not turn back; someday, he said, children would benefit from the trail Perry had blazed.

This turned out to be true, and not only in the ways one might expect. Last October, I moderated a conversation at Lipscomb Academy Middle School in Nashville. Jessie, her sister Annie, and Perry’s former middle-school math teacher were the panelists.

There was special meaning to the fact that Lipscomb had selected the Young Readers edition of Strong Inside (the biography of Wallace) as its all-school read. The school is affiliated with the churches of Christ. In 1966, Wallace was ejected from a white church of Christ adjacent to the Vanderbilt campus simply for being black. The children in the audience were the figurative and, perhaps in some cases, literal descendants of the men who had booted Wallace. The moment was not lost on Jessie as she addressed the students that day.

“I’m so delighted to be with you,” she said, “because you are a symbol of what my father prophesied in 1966. He said boys and girls in the future will learn about Perry’s struggles, and they will have a deeper appreciation for all of God’s creatures. He said love will always win over hate.”

When Jessie finished speaking, the diverse group of students erupted in a spontaneous standing ovation. Then they lined up, one by one, to give her hugs. This was a beautiful sight and, thankfully for Wallace and his family, was one of many that took place throughout the past decade. A gradual reconciliation began during the last years of his life, beginning in earnest when Wallace’s Vanderbilt jersey number was retired in 2004 and when he was inducted into the inaugural class of the Vanderbilt Athletic Hall of Fame four years later.

Wallace brought tremendous grace to these acts of reconciliation, offering forgiveness and inspiration. He often said that “reconciliation without the truth is just acting,” and in his case, because the truth was out in the open, the healing was real. Many of Wallace’s former classmates began to express deep regret that they had not done anything to support him when he needed them most. He always listened patiently, always forgave.

Younger generations gravitated to him. Each of the two most recent incoming first-year classes at Vanderbilt has been required to read his biography. They learned that Wallace was an extraordinary person, from his birth in 1948 until his death 69 years later. As a kid he taught Sunday school and practiced playing his trumpet four hours a day. He walked to the neighborhood library just to read on weekends, and he could dunk a basketball by the age of 12. He was valedictorian of his high school and the most popular student.

He was the slam-dunking captain of a team that won three straight state championships, including the first integrated state tournament in Tennessee history, when his Pearl High team capped off an undefeated season with a championship victory against a white school from Memphis. It came on the same night the all-black starting five at Texas Western made history at the collegiate level, beating Adolph Rupp’s all-white Kentucky Wildcats.

At Vanderbilt, Wallace earned an engineering degree and was influenced by civil rights figures including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Stokely Carmichael, Fannie Lou Hamer and Robert F. Kennedy, all of whom he met and spoke with when they visited campus. He was drafted by the Philadelphia 76ers and played one year of minor-league basketball, but understanding that his “legs might last five more years but [his] brain forever,” he quit basketball to pursue a legal career. Jack Ramsay, the 76ers’ coach, wrote one of his letters of recommendation to the law school at Columbia, where Wallace earned his degree before becoming an attorney for the U.S. Department of Justice. For more than 20 years before his death, Wallace was a beloved professor of law at American University.

With all he had accomplished, he often said he was proudest to be a husband and father.

After a campus lecture last year, Vanderbilt students lined up to meet the man they had only read about. One by one, they shook Wallace’s hand, asked him to pose for selfies, thanked him for his courage. Perry Wallace was beaming. He always said his experience was worth it if others learned from it. He was proud to see a Vanderbilt that looks far different today than the one where he felt only exclusion: This year’s first-year class is the most diverse (45 percent minority) and accomplished (90 percent in the top 10 percent of their high school classes) in the school’s history.

Wallace told students they were on his mind, even before they were born. Even in those pioneering days, it was never about him. He remembered the words of his father. Someday young people would live in a better world, have more opportunities, because of what he endured.

He lived to see it.

Andrew Maraniss, BA’92, is a writer-in-residence at Vanderbilt University and the author of Strong Inside, a New York Times best-selling biography of Perry Wallace. A Young Readers adaptation of Strong Inside was named among the top 10 biographies for youth in 2017 by the American Library Association. Follow Maraniss on Twitter @trublu24. This essay originally appeared on the website TheAthletic.com.

Wallace Named 2017 Distinguished Alumnus

The Vanderbilt University Alumni Association Board of Directors has selected Perry Wallace, BE’70, as recipient of Vanderbilt’s 2017 Distinguished Alumni Award, the highest honor bestowed on a member of the university’s alumni community. In December, Gail Carr Williams, David Williams II and their children made an inaugural contribution to fund the Perry E. Wallace Jr. Basketball Scholarship to provide support for student-athletes. To make a contribution to the fund, go to vu.edu/wallacescholarship.