By Cindy Thomsen

James Patterson, MA’70, breathes rare air.

His books line the walls in airport shops. They’re tucked into beach bags amid the towels and sunscreen. They’re on sidewalk kiosks and bedside tables around the world.

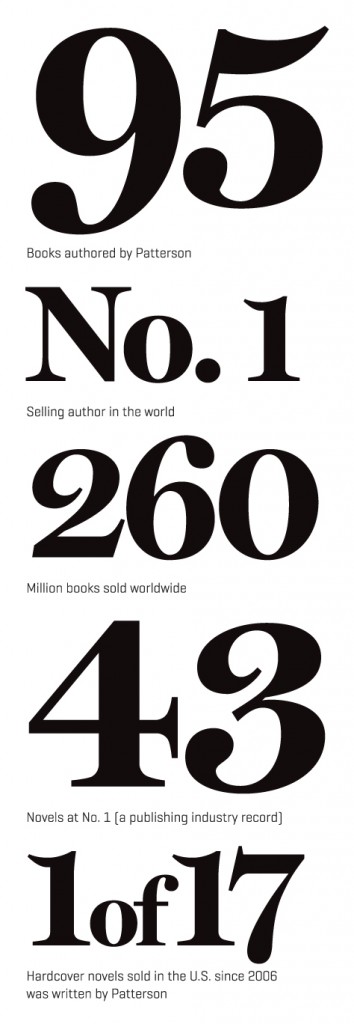

In 2010 he sold more books than John Grisham, Stephen King and Danielle Steele combined. Those sales, $84 million worth, came from a combination of books written for adults, teens and preteens. In all, he had 20 titles on the year-end best-seller lists.

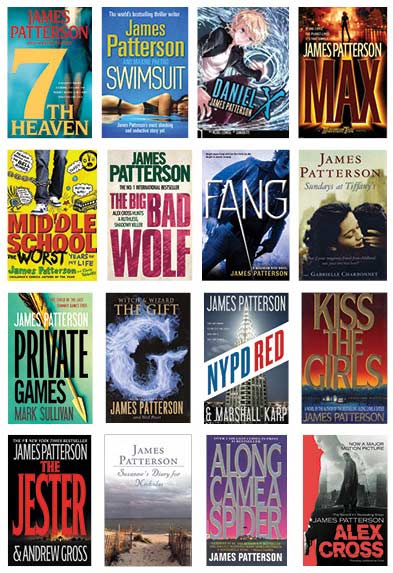

Patterson’s mega-success came with the creation of Alex Cross, a Washington, D.C., detective and psychologist who has been featured in more than 15 novels, including three—Kiss the Girls, Along Came a Spider and Alex Cross—that were made into major motion pictures.

Today, however, Patterson is more thrilled to be writing about the lives and times of middle-school students rather than murderers, kidnappers and terrorists. Those books include the award-winning Maximum Ride, Daniel X and Witch & Wizard series for young adults.

“The kids’ books I’m writing today are actually the best that I’ve done and the most interesting,” he says. “It’s good to keep adults reading and enjoying it, but it’s crucial to make readers out of kids.” In 2011, Patterson wrote a CNN.com editorial titled “How to Get Your Kid to Be a Fanatic Reader.” The average CNN.com editorial receives 500 to 600 recommends. Patterson’s garnered more than 73,000. He paid to have it run in USA Today, and it proved so popular there that the paper ran it two additional times at no charge.

“It’s a very good piece,” Patterson says. “It’s a piece that strikes a chord with parents and teachers and librarians. When kids aren’t reading, adults feel guilty and want any kind of help they can get. This piece is useful and helps them get their kids reading.”

CHECK THE ATTITUDE

As the father of a middle-school-aged son, Patterson knows that many boys are reluctant readers. The key, as he points out in the editorial, is to be concerned less about what they’re reading.

“Teachers and school administrators might want to consider this,” he wrote. “In many schools there’s a tendency not to reward boys for reading books like Guinness World Records or Sports Illustrated Almanac or The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll. Too often, boy-appealing books are disproportionately overlooked on recommended reading lists.

“Big mistake. Tragic mistake. Avoidable mistake. It’s all about attitude. If your kids’ school library isn’t a boy magnet, the school probably needs to check its attitude.”

“My mother was a teacher and I’m sure she encouraged me to read, but I wasn’t a huge reader until after high school,” says Patterson. “What discouraged me were the things I was asked to read. I was a very good student, but I wasn’t a big reader.”

In fact, Patterson claims he didn’t become a serious reader until he started working at a mental hospital. The hospital had some well-known patients during his time there, including James Taylor and Ray Charles.

“I worked the night shift and just started reading like crazy,” he says. “I was reading four or five books a week and it was all serious stuff, not the kind of junk I write.”

His wish, though, is for children not to wait as long as he did to discover the joys of reading—and he sees middle school as the best time to hook a young reader. In fact, he believes those middle-school years are so crucial that he’s written two children’s books about that time: Middle School, the Worst Years of My Life (2011) and Middle School: Get Me Out of Here! (2012). He predicts the second one will be his top seller of all time. While Patterson is best known for his thrillers, he has no difficulty relating to children.

His wish, though, is for children not to wait as long as he did to discover the joys of reading—and he sees middle school as the best time to hook a young reader. In fact, he believes those middle-school years are so crucial that he’s written two children’s books about that time: Middle School, the Worst Years of My Life (2011) and Middle School: Get Me Out of Here! (2012). He predicts the second one will be his top seller of all time. While Patterson is best known for his thrillers, he has no difficulty relating to children.

“I write a lot of different kinds of books. I’ve written love stories, one historical novel, and a couple of nonfiction,” he says. “If I feel an emotional connection to that kind of book, I can write it. I’m very comfortable with kid stuff—I know what it’s like to be 13.”

Patterson’s writing obviously resonates with children. In 2010 he won the Children’s Book Council’s Author of the Year Award, which is voted on by children.

“I was nominated for the award, and my son, Jack, said, ‘Don’t get me wrong, Dad, I really like your books, but Rick Riordan’s going to win,’” remembers Patterson, who lives with his family in Florida. “I took him and my wife to New York City, and I won! I held up the statue and said, ‘This is for you, Jack.’ It’s nice that he’ll always have that memory.”

Patterson does believe some fundamental differences exist between yesterday’s children and today’s.

“I think we have to earn children’s respect more today—that you don’t automatically have it because you’re a teacher or a parent,” he says. “They expect more, too. They think it’s their birthright to have an iPod or iPad. They just assume it’s part of the deal of being a kid.”

In an effort to further facilitate childhood reading, Patterson created ReadKiddoRead.com. The site offers detailed reading lists for children, lesson plans for teachers, and even a community page where members can post.

“Books are the only place where you really can have a wide experience and learn different points of view about life,” Patterson says. “You can find out what people are really like and learn what they’re really thinking. You learn compassion, and that’s not available on television.”

There’s also the possibility that childhood reading could germinate the seeds of a career. Patterson points out that many of today’s scientists first became interested in the field by reading science fiction. Science fiction, he says, opens minds to what could be possible.

“I think that in every state we should have a place where kids who are really interested in science can go and there’s no ceiling,” Patterson says. “We could have something right here at Vanderbilt where kids could come in twice a week and just get their minds blown.”

BUILDING BETTER READERS

Naturally, an author needs readers to be successful. Building better readers is a mission in which Patterson is wholeheartedly involved.

“I do a lot of things to try and get kids reading,” Patterson says. “Obviously, I think that turning out better teachers is one of those. That’s why my family has scholarships at Vanderbilt and at other places.”Patterson researches schools of education across the country and establishes scholarships at the best ones. The Patterson Scholars program was established at Vanderbilt’s Peabody College of education and human development in 2009. Preference is given to students majoring in elementary or secondary education, and specific preference is reserved for students participating in educational community service. Nine students are currently in the program. Patterson also funds scholarships at Wisconsin, Tulane, Michigan State, Appalachian State, and at his undergraduate school, Manhattan College. He will add more schools in the near future.

“By supporting future teachers I’m dealing with the possible,” Patterson says. “When I talk to people involved in education, I find out what we can do to move the ball forward. We don’t have to score a touchdown—we just have to move the ball forward.”

While reading improvement is his primary goal, Patterson hopes that schools see the bigger picture and start teaching children to think on a deeper level.

“When you get into the habit of thinking deeper, you don’t just blurt out a quick response to a question or problem,” he says. “That’s one of the big problems with kids and adults both today. They hear one little thing on TV and the polls go crazy. I think that in European countries, people are trained not to stop at the first impression—they take another step and look a little deeper.”

CONFIDENCE IS KEY

A young author needs confidence, and one Vanderbilt professor, Walter Sullivan, gave Patterson just that. Sullivan was a Southern literature expert who published criticism, novels and short stories.

“Sullivan said to me, ‘You can write—you can do this if you want to,’” Patterson says. “That was extremely important to me because I thought it was presumptuous to think that I could write well and that I could even consider making a living doing it. It was a real turning point for me.”

Patterson believes today’s professors can similarly inspire their students.

“We need to come up with programs that are going to make the kids coming out of Vanderbilt more effective and help them be leaders,” he says. “A school can grow both the sense of community and individuality in its students. Schools like this need to be thinking about creating leaders—and not just leaders with big egos, but leaders with a sense of community.”

Young readers also need to gain confidence in their abilities.

“I’ll go into schools and start talking to kids about soccer,” he says. “I’ll say, ‘Are you better now than you were four years ago?’ and they’ll say, ‘Yay, we’re better now!’ I’ll say OK, it’s the same with reading. If you do more of it, even if it’s reading comic books, you’ll get better. It won’t be so much of a struggle.”

The bottom line for Patterson is that his children’s books are his most gratifying work because of the potential for making a real difference.

“We can’t solve the health care problem,” he says. “We can’t make Wall Street more moral or ethical. But we can, most of the time, affect reading in our homes and in our towns. We’re not going to solve every problem, but we can almost always make a 100 percent improvement.”