While he was cooking dinner, phone in hand, Alexandre Tiriac noticed an email from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. The organization—a grantmaking institution founded in 1934 by industrialist Alfred P. Sloan Jr.—had written to tell him he’d been selected for one of its prestigious research fellowships. “Yes, I am too connected to my phone,” Tiriac said, laughing.

Awarded annually since 1955, the fellowships honor extraordinary U.S. and Canadian researchers who stand out as the next generation of leaders for their creativity, innovation and research accomplishments. Tiriac, an assistant professor of biological sciences and Hooley Family Dean’s Faculty Fellow in Biological Sciences at Vanderbilt, is part of the 2025 class.

“The prestigious Sloan fellowship is a well-deserved acknowledgement of Alexandre’s pioneering research on the development of neural circuits,” said Timothy P. McNamara, Searcy Family Dean of the College of Arts and Science. “Alexandre is helping to uncover intriguing mysteries about the nervous system, such as how neural activity affects the development of the ability to see. We are proud to have him as part of the thriving Vanderbilt scholarly community.”

BRAIN MATTER

Born in France, Tiriac moved to California when he was 13; he found a passion for developmental neuroscience research during his undergraduate studies at UC Davis. His Ph.D. track took him to the lab of Mark Blumberg at the University of Iowa, where he studied how REM sleep twitches during development trigger feedback throughout the sensory and motor system.

But it was after pursuing his postdoctoral studies in Marla Feller’s lab at UC Berkeley— where he studied how spontaneous activity in the retina shapes the development of visual circuits—that Tiriac realized he valued mentoring just as much as researching.

FUSING MENTORSHIP AND RESEARCH

That realization brought him to Vanderbilt in 2020, where he leads the Tiriac Lab, a systems and developmental neuroscience laboratory that supports several projects that are working to understand the role of spontaneous movement in sensory circuits. They focus on the process during development.

“I am fascinated by brain plasticity, which is a feature that allows our brains to adapt to sudden changes. The brain is never more plastic than it is during development—it’s part of the reason why kids can learn skills at such an accelerated pace compared to adults,” Tiriac said. “However, a plastic brain is also more amenable to being negatively altered by its environment. Thus, in addition to being fascinated by the basic science behind brain plasticity, I hope to gain a mechanistic understanding of neurodevelopment disorders and harness the powers of plasticity to enhance human health.”

IN THE LAB

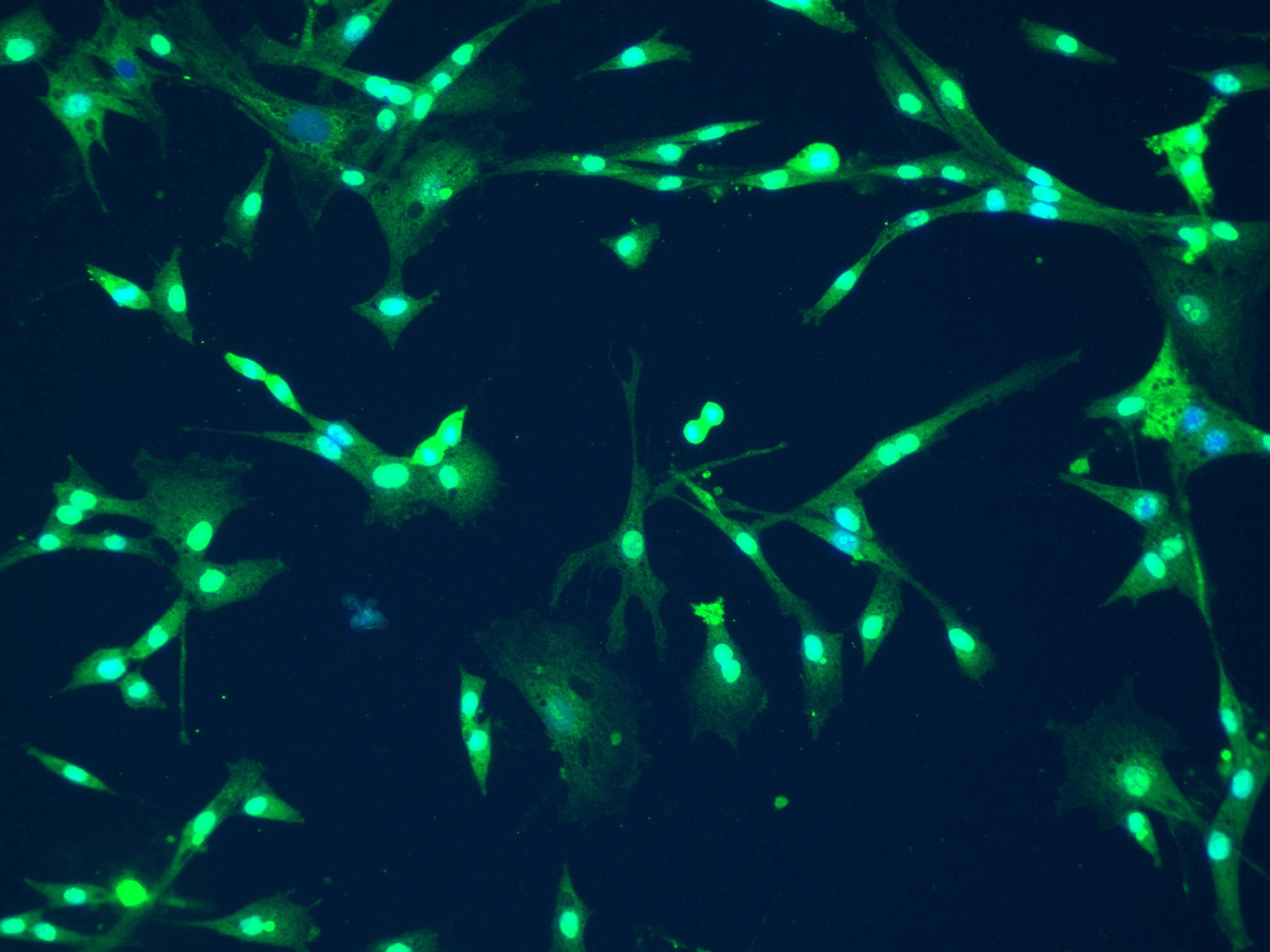

Research at the Tiriac Lab is focused on understanding brain development during early life, when neural connections are rapidly formed and refined. This refinement process relies on neural activity that is produced spontaneously in the brain. The spontaneous activity is not random, it has patterns that are thought to simulate future sensory experiences.

“The goals of our research are to understand the mechanisms underlying the generation of patterned spontaneous activity and to use this information to study its role in development and disease,” Tiriac said.

One of the areas of study for the lab is the visual system. The team studies retinal waves, or bouts of spontaneous activity that start in retinal neurons and drive neural activity in the entire visual brain. Their aim is to uncover circuits that are responsible for generating retinal waves, which may not only help to better understand visual development, but also reveal potential therapeutic avenues.

The team also works on a research program aimed at studying spontaneous activity in the proprioceptive and somatosensory system. In those systems, there are bouts of spontaneous activity that trigger discrete muscle twitches specifically during REM sleep. Much like retinal waves, these twitches cause the entire sensory brain that encodes the body to be activated. The lab’s researchers work to understand if that neural activity has a developmental function. The hope is that their work will help answer the perennial question of why we sleep so much when we are young.

A MARK OF EXCELLENCE

Each year, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation disburses approximately $80 million in grants in four broad areas: direct support of research in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and economics; initiatives to increase the quality and diversity of scientific institutions and the science workforce; projects to develop or leverage technology to empower research; and efforts to enhance and deepen public engagement with science and scientists.

Fellowship winners receive a two-year, $75,000 fellowship that can be used flexibly to advance the fellow’s research. Tiriac says he will use the funds to pay personnel who are hard at work toward the lab’s research goals.

Winning a fellowship is notable; just 126 were awarded this year. Fifty-nine former Sloan Research Fellows have won Nobel Prizes, and 17 have won the Fields Medal in mathematics. Since the first Sloan Research Fellowships were awarded in 1955, 23 faculty from Vanderbilt University have received a Sloan Research Fellowship.

“It is such an immense honor to receive this award and have our lab’s work and mission be recognized,” Tiriac said. “More than that, I am enormously thankful for the outstanding mentors and colleagues that have enabled my career and research.”

Vanderbilt’s submissions for awards like the Sloan fellowships are supported by Research Development and Support (RDS), which offers proposal development assistance for both private (foundations) and federally funded opportunities. Services include searches for new sponsors, coordination and team building for proposals of any size, content development, and draft review. RDS further supports faculty by building relationships with external sponsors, hosting workshops, and providing guides and language for common proposal requirements. RDS is in the Office of the Vice Provost for Research and Innovation. To learn more about RDS or request services, contact us at rds@vanderbilt.edu.