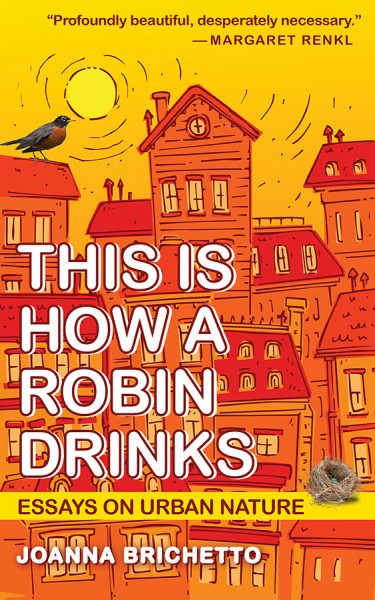

Reprinted courtesy of Trinity University Press. This excerpt appeared in the book This is How a Robin Drinks: Essays on Urban Nature, by Joanna Brichetto, MA’06 (JLBrichetto@gmail.com), published in September by Trinity University Press. For more information, please visit tupress.org.

Reprinted courtesy of Trinity University Press. This excerpt appeared in the book This is How a Robin Drinks: Essays on Urban Nature, by Joanna Brichetto, MA’06 (JLBrichetto@gmail.com), published in September by Trinity University Press. For more information, please visit tupress.org.

“Let’s go see the ice mushrooms,” Michael said. His tone implied the trip would be worth trading a warm house for a cold drive, but I didn’t expect much. I figured he meant frost heaves, like when frozen soil burps itself into needled buttes. Heaves happen in the lawn sometimes—they rise an inch or so tall—and then crrrrunch underfoot in the most satisfying way.

But no, he led us to a long meadow deep in Warner Park with hundreds and hundreds of what I can now call frost flowers: white ice formations abloom from the base of nearly every meadow stem—as wheels, arabesques, bottlebrushes, and especially, miraculously, as ribbons snaking through stubble, looping back on themselves in tight slaloms, pretzeling around dead leaves and brambles. The ice was corded, striated—not like grosgrain ribbon on the transverse, but parallel, like that fancy ribbon candy I’ve never seen anyone actually eat. The tallest stems—up to six feet—wore capes frozen in mid-billow, as formal as a Leonardo drapery study.

When morning sun hit them, they glowed.

These, we do not step on.

Clueless as to exact cause and certainly clueless as to the species of real flower they sprang from, we marveled, we knelt, we poked, and a few, we licked and bit.

Frost flowers.

Right now, these native “flowers” are blooming in Nashville—at least, until they melt, which is typically right after they form. Frost flowers are winter ephemerals. They happen when air temperature drops below freezing and warm groundwater rises to extrude itself through the conduit of a real flower stem, especially if that stem is a white crownbeard (Verbesina virginica). “Ice segregation” is the process at work. Water and vapor freeze on contact with air, and waves from within push older crystals forward and out. Crownbeard’s winged structure aids the process. Other species can produce frost flowers, but white crownbeard is such a common enabler that the plant’s most common common name is frostweed.

The taller the plant, the taller the ice sculptures. The short stalks I found today had been mown by the city, and illustrate another good reason to put off mowing till spring. Spent flowers left standing can feed seed-eating birds, house overwintering pollinators, give cover for wildlife, and make spectacular ice art.

This year, I missed the first crop at Warner, which was the November morning after first frost. I missed the next crop in early December because I was home with a sick kid. I was bummed.

And then yesterday, washing dishes and feeling sorry for myself, I remembered my friend Gail had given me a baby white crownbeard last summer. A native aster had piggybacked in the same pot, and in my ratty garden had grown so much taller and bushier than the crownbeard I’d forgotten about the shorter gift. I ran coatless to the backyard and there it was: my own private frost flower, spinning a curtain between two dried stalks.

I hope my little plant likes my garden. I hope it can seed itself into a flurry, a snow shower, a snowstorm, a blizzard.

Not that white crownbeard is only valuable in winter. It’s the larval host plant for several butterflies, and from July to October is a good source of nectar. The true blossoms are small but lovely: rays and discs as white as the stem’s winter wings.

I almost missed the mown versions today. On an urgent whim that struck with only an hour till school pickup, I drove to the park in search of leftover ice. There was no time to make it to the long meadow, and besides, sun would have soaked those into the soil by noon. A weedy north-facing lee was my last hope till next winter.

I found them where honey locust pods drop on the road near the Cane Connector trail, at the line where the two Warner parks divide. I stopped the car and reversed, but what I thought were frost flowers was trash: a white Walmart bag, a pair of men’s briefs, an empty juice bottle milky white against green-brown grass. They all look like ice sculptures from a moving car.

But there—at the same height as the wads of toilet paper and sandwich foil—curved dozens of stubby frost flowers, still frozen at two o’clock in the afternoon thanks to the shade of a sugar maple and a berm of privet. The contrast of treasure and trash (and trash shrubs) made me happy, and I was glad that despite the city’s effort to tame the roadside, the ice had enough wild to work with. It made do.

These, however, I do not lick.

I did find one honey locust pod that didn’t rattle when I shook it. It was rusty brown, nearly as long as my forearm, and sure enough, inside between seeds was still goopy and sweet. The taste is sort of like dates or fig, and with a smoky note best savored on a slow exhale, mouth shut. I was in a hurry now, and I sucked the torn end on the way to school, driving fast past drifts of frost flower—four feet tall—that I had not seen on the way in, along the shadowed side of the highway.

Follow Joanna Brichetto on Instagram @jo_brichetto or at SidewalkNature.com