By Ray Waddle, MA’81

In fourth grade, James Lawson had a bloody fight with a white kid who called him a racial slur. Later that night, his mother quietly said, “Jimmy, what good did that do? There has to be a better way.” Those words guided him ever after.

By the time Lawson arrived at Vanderbilt Divinity School in 1958, he was a 30-year-old Christian pacifist who had been in prison for opposing war. As a Methodist minister, he marshaled the ideas of Gandhi, Henry David Thoreau and Jesus against midcentury segregationism. He believed love is the only social force to ensure the full status of everyone’s humanity. “We must live by love, not fear,” he often said. “It’s the only way for human aspirations to be fulfilled.”

When Lawson chose Vanderbilt, he chose Nashville too. Off campus he taught nonviolent strategy to student activists committed to dismantling the region’s Jim Crow traditions.

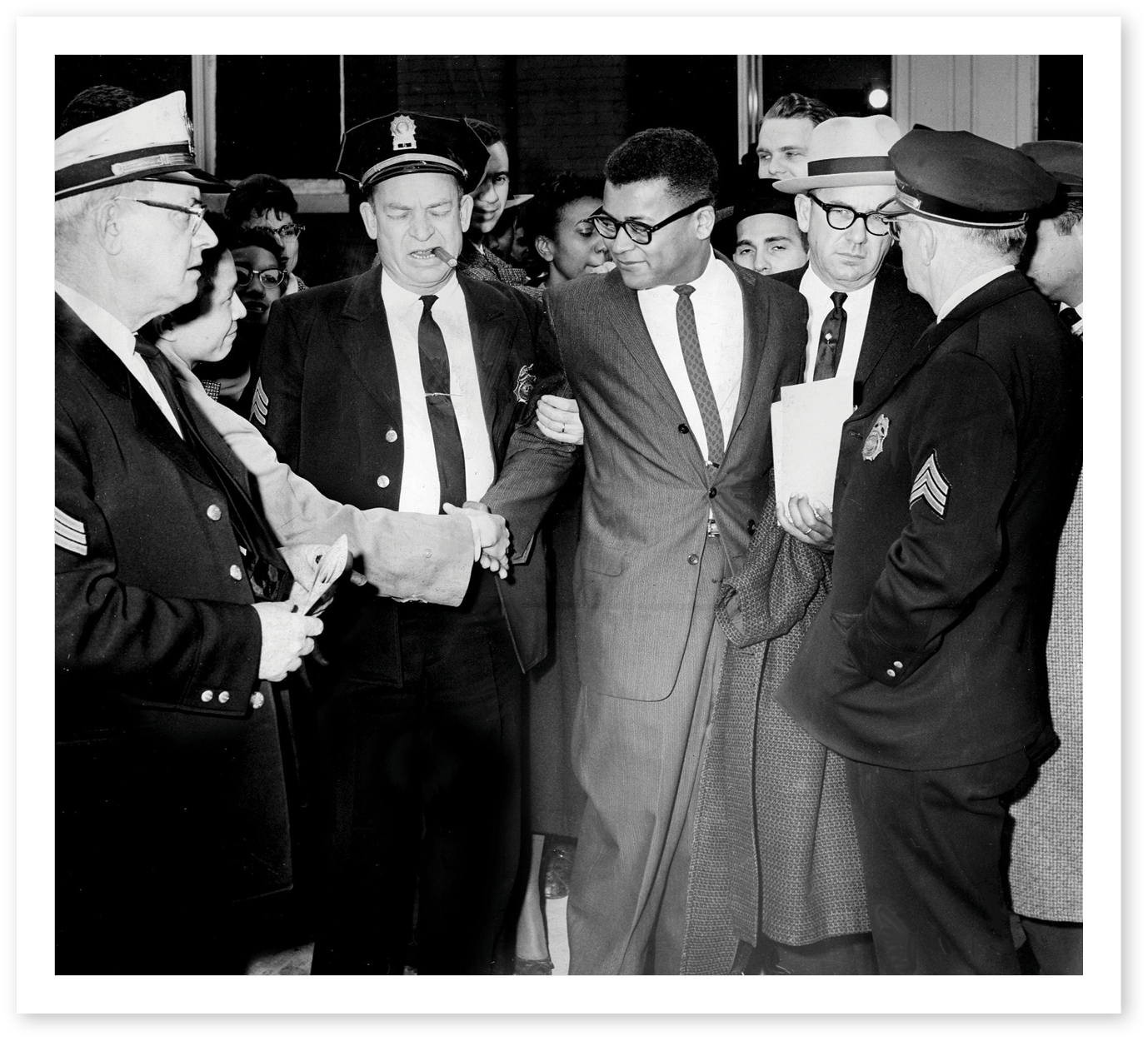

At the time, Vanderbilt and Chancellor Harvie Branscomb were on a gradualist path to racial integration. The pace was slow—and on a collision course with a postwar liberationist spirit. By March 1960, Lawson was overseeing some very public anti-segregation sit-ins. This became a problem for Vanderbilt: A university student was leading a movement that disregarded local laws. Though Lawson’s graduation was mere weeks away, he was expelled.

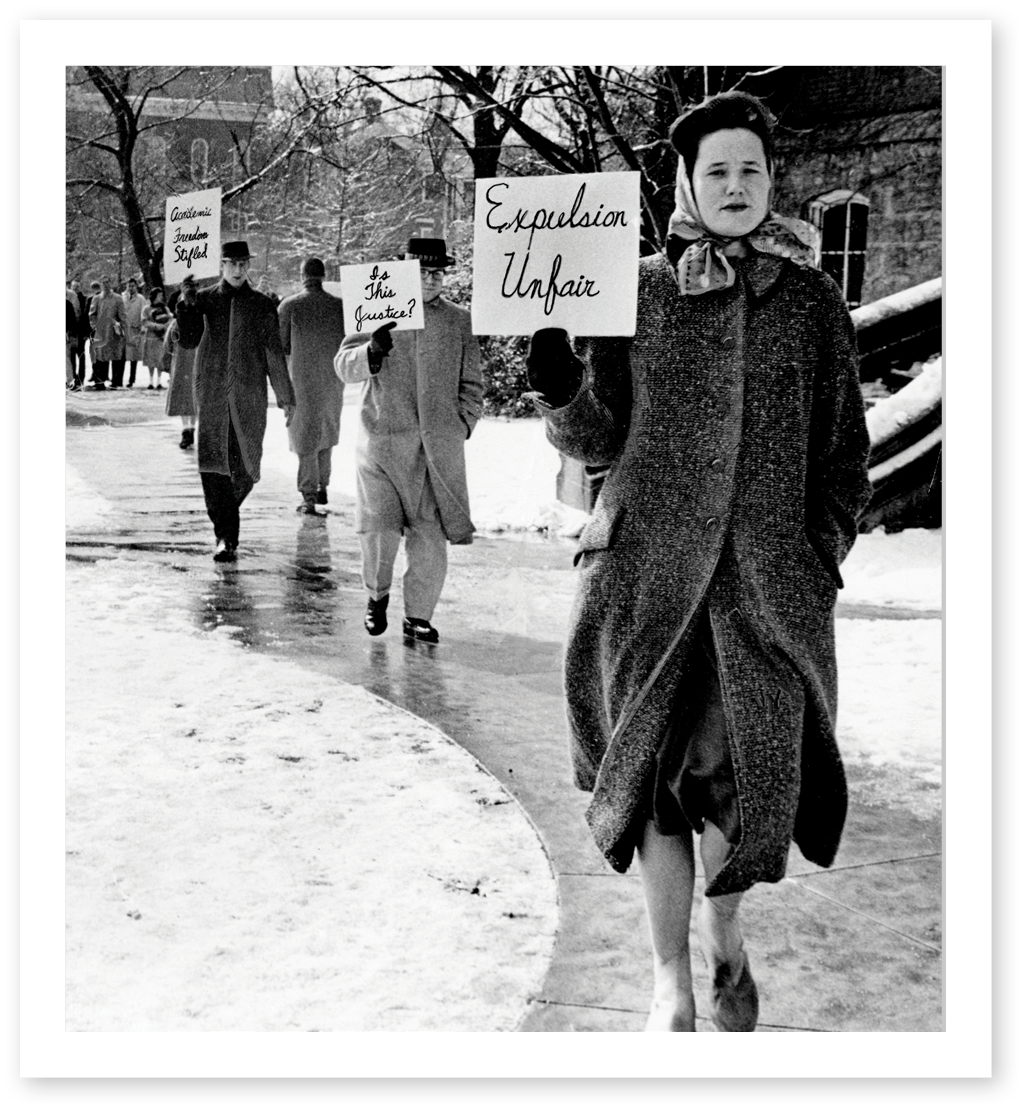

The expulsion triggered a campus crisis. Many professors took steps to resign, especially at the Divinity School, which now faced existential turmoil. National press followed the saga daily. The publicity was excruciating to VU leaders. A last-minute arrangement allowed Lawson to take his degree, and faculty withdrew their resignations. Meanwhile, Lawson had transferred to Boston University and soon graduated.

The Lawson ordeal eventually took a constructive turn. By 1962, Vanderbilt decreed that prospective students for all its schools would be considered regardless of race. Faculty exerted more administrative power. Student disciplinary procedure was reformed. The Divinity School would make new faculty hires, renewing its mission and prestige.

Lawson soon returned to Tennessee as a Memphis minister. He reconnected with Vanderbilt, pursuing a doctor of ministry degree in 1970. His human rights advocacy expanded to fair wages, earth care, and gender and sexual equality. Even after he moved to Los Angeles to lead a church there in 1974, Vanderbilt denizens sought his counsel.

His witness deepened the Divinity School’s justice-minded identity. By the 1990s he was a cherished VDS elder. In 1996, he received the school’s first Distinguished Alumni/ae Award. He was a visiting professor in 2006. Metropolitan Nashville bestowed its own affection, opening the James Lawson High School in Bellevue in 2023.

The commitment and grace Lawson exhibited during the 1960 firestorm looked all the more extraordinary in a new century of intensified rancor and violence. University honors culminated in 2022 with the launch of the James Lawson Institute for the Research and Study of Nonviolent Movements. The institute website declares: “Your life speaks even now and asks: How shall we change the world?”

“Violence has no practical results toward building a strengthened community or solving the problems of human prejudice, bias and injustice.”

—Rev. James Lawson

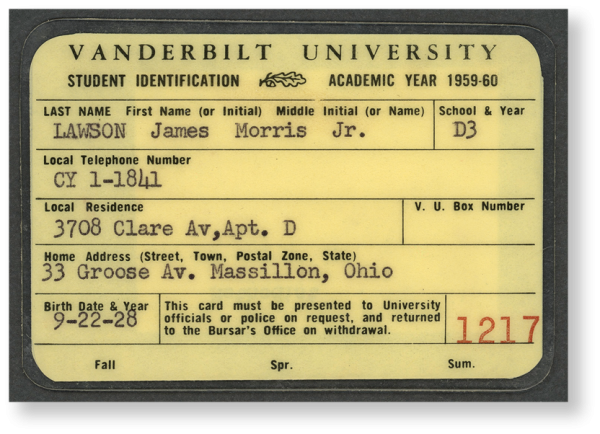

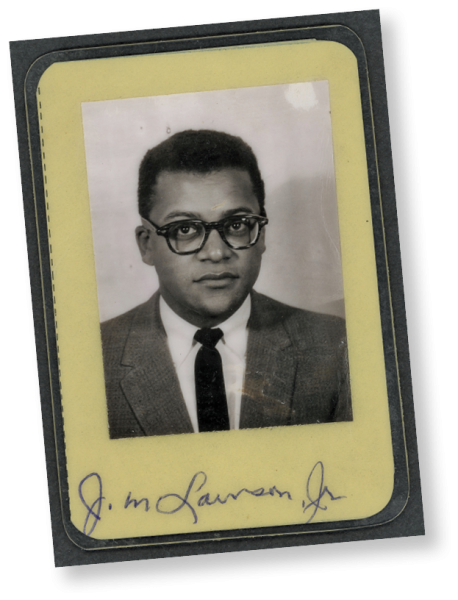

At left and below is Rev. James Lawson’s 1959 Vanderbilt identification card from when he was a Divinity School student. A Pennsylvania native who grew up in Ohio, he arrived at Vanderbilt as a third-year transfer student from Oberlin College School of Theology in Ohio. That same year, 1959, he married Dorothy Wood, a TSU graduate who would work alongside him through the decades as a civil rights advocate and teacher. (James Lawson Collection/VU Special Collections and University Archives)

At left and below is Rev. James Lawson’s 1959 Vanderbilt identification card from when he was a Divinity School student. A Pennsylvania native who grew up in Ohio, he arrived at Vanderbilt as a third-year transfer student from Oberlin College School of Theology in Ohio. That same year, 1959, he married Dorothy Wood, a TSU graduate who would work alongside him through the decades as a civil rights advocate and teacher. (James Lawson Collection/VU Special Collections and University Archives)

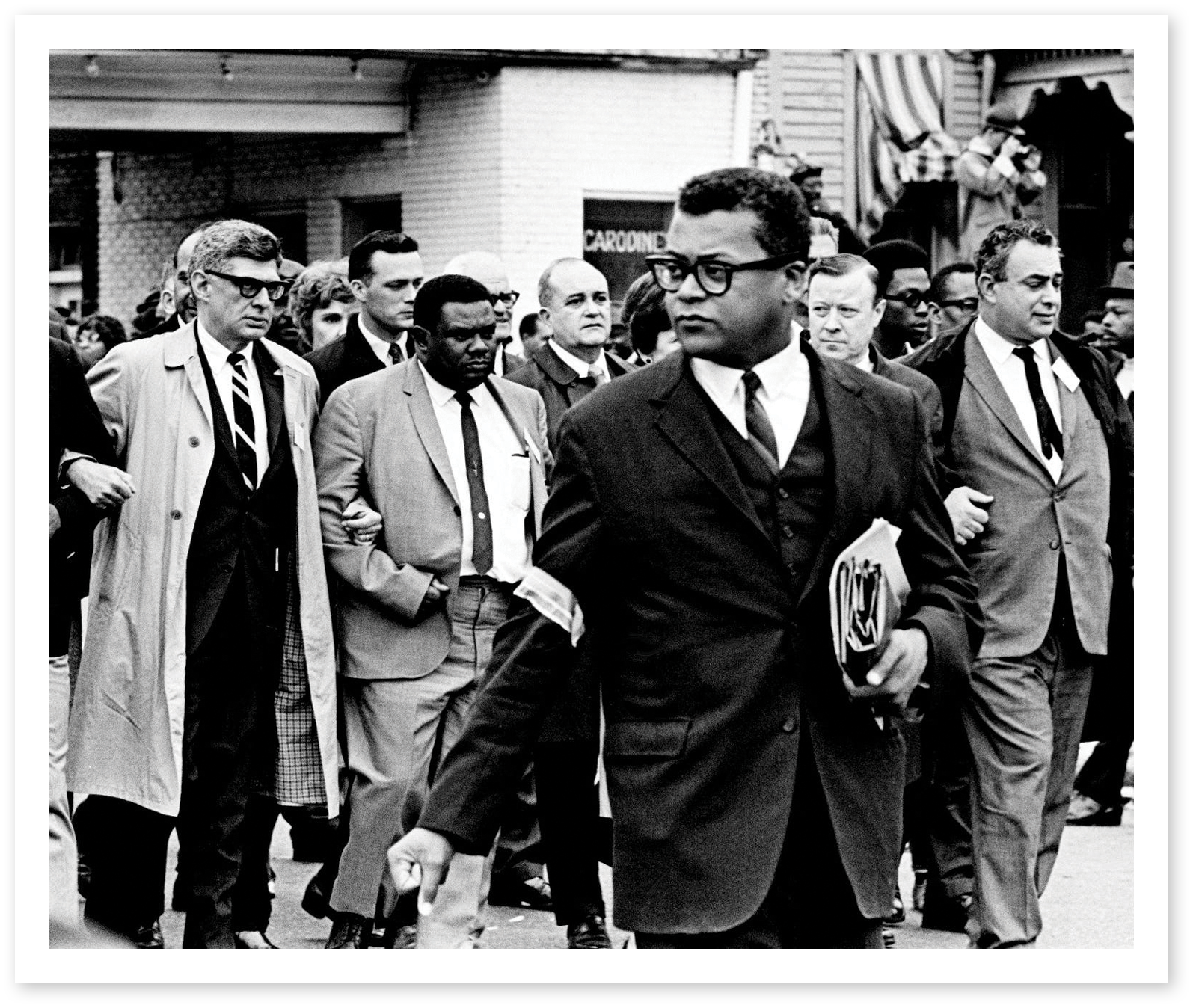

Below, Rev. James Lawson, in Memphis on April 8, 1968, joins 25,000 others on a silent march to honor the late Martin Luther King Jr., who was killed four days earlier. Lawson had moved to Memphis as a minister in 1962, involving himself in local justice causes throughout the decade. This included the 1968 sanitation workers’ strike for better wages. Lawson had invited his friend Dr. King to Memphis that spring to galvanize the protests. (Bill Preston/The Tennessean)

Rev. James Lawson protests racial apartheid on March 15, 1978, in front of Rand Dining Center at Vanderbilt. By now he was a minister at Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles, but he periodically returned to campus. The 1978 “speak out” event against the Davis Cup tennis matches at Vanderbilt, which included a team from South Africa, drew more than 100 faculty members from seven Nashville colleges and universities. (Nancy Warnecke/The Tennessean)

Rev. James Lawson protests racial apartheid on March 15, 1978, in front of Rand Dining Center at Vanderbilt. By now he was a minister at Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles, but he periodically returned to campus. The 1978 “speak out” event against the Davis Cup tennis matches at Vanderbilt, which included a team from South Africa, drew more than 100 faculty members from seven Nashville colleges and universities. (Nancy Warnecke/The Tennessean)

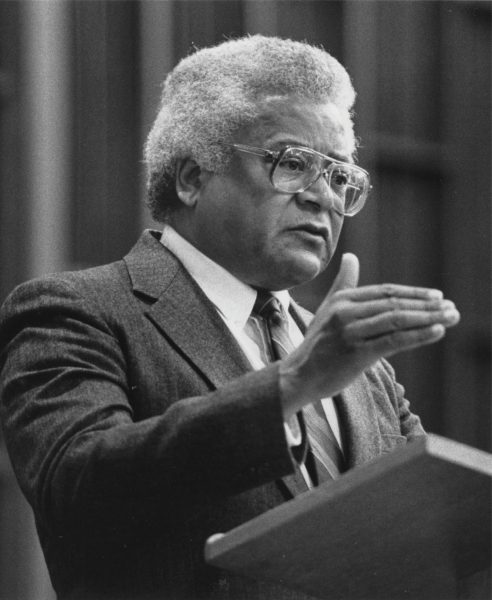

Left, Rev. James Lawson speaking at Benton Chapel in 1987 (James Lawson Collection/VU Special Collections and Photo Archives)

Left, Rev. James Lawson speaking at Benton Chapel in 1987 (James Lawson Collection/VU Special Collections and Photo Archives)

Right, Rev. James Lawson gave the keynote address for the 2016 MLK Lecture Series held in Langford Auditorium on Jan. 18. Here he speaks with students backstage at the auditorium. (John Russell/Vanderbilt University)