Acid mine drainage. Digitally printed legal documents. Drone photographs. Core samples. Appalachian bituminous coal. The artists represented in Extraction/Interaction—the Curb Center’s fall exhibition—use these and other materials to create bodies of work that galvanize responses and resistance to the climate crisis. Featuring the work of Will Wilson, Eliza Evans and John Sabraw, Extraction/Interaction considers how climate grief can transform artistic practice into a mechanism for positive environmental impact.

Extraction is the conceptual thread that unites the work of Evans, Sabraw and Wilson. Eliza Evans’ project All the Way to Hell is an artist and landowner’s attempt to use the power of collective action to thwart fracking interests with eyes on her patch of Oklahoma. When Evans learned she had inherited three acres of property in Oklahoma from a family member, she came face-to-face with the bureaucratic intricacies surrounding mineral rights on private property. Even if she refused to sign over the mineral rights to her Creek County property in an effort to prevent fracking, she could still be forced to sell under a “forced pooling order” if enough neighboring property owners agreed to sell to frackers. These rights, as the title references, extend “ad infernos,” or “to hell.” As Evans notes on the project’s website, “In all states, mineral rights supersede surface rights, and mineral ownership may be the most powerful, racialized and inequitable form of property ownership in the U.S.”

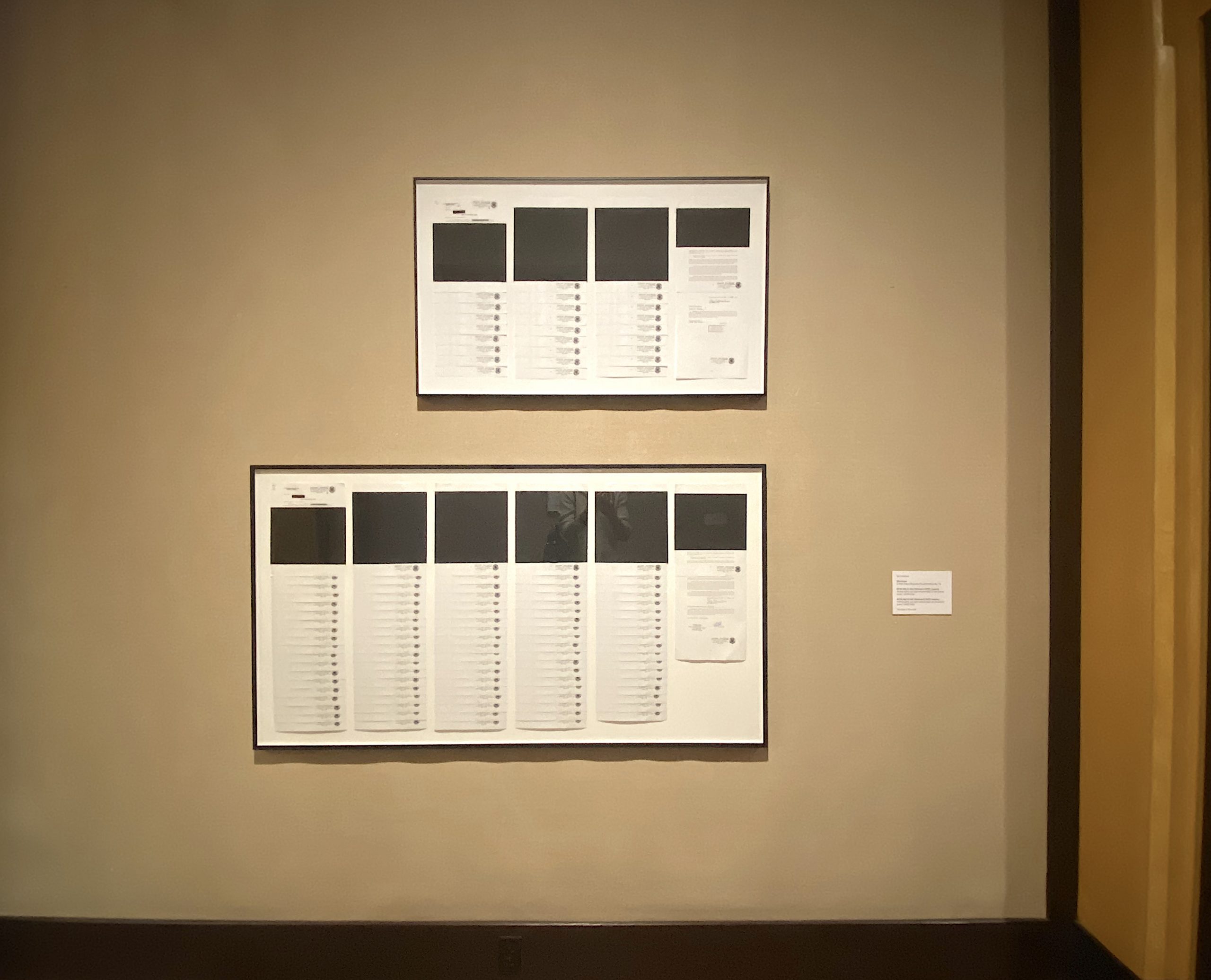

All the Way to Hell is a plan to resist these odds through bureaucratic burdening. By splitting the mineral rights between thousands of participants, Evans could force fracking companies to spend resources and staff-hours contacting each individual owner. Even if a pooling order takes place and all owners are forced to sell, the company would then be left with the administrative burden of paying royalties every quarter to the now more than 8,000 mineral rights owners. Samples of these contracts are displayed at the Curb Center, along with mineral core samples from the Permian Basin, the oil

fields near Midland, Texas. These core samples are often taken by oil and gas companies to plan their extraction of resources—but here, these samples show what is owned and protected by the collective.

John Sabraw’s work also stems from resource extraction, but instead of preventing future extraction, his work begins in our extractive past. Before regulatory bodies existed in the United States, we were already building mines. Many of these were shuttered long before we understood how to safely close them down. Heavy rains can sweep harmful chemicals from these untended sites into our water systems, killing wildlife. One such pollutant is iron oxide, a common ingredient in pigments. When Sabraw visited a tainted river in Ohio—a state with around 6,000 abandoned mines—he wondered, “Can I paint with this?”

The work Sabraw contributed to Extraction/Interaction all began as harmful chemicals. Iron oxide and bituminous coal create abstract images that bring to mind forests, deltas and riverways. Sabraw also plans to make these pigments available to other artists in the future, some at no cost for those with a sustainable artistic practice.

The issue of abandoned mines also has a direct human cost (though, how separate is humanity from our ecosystems?) as Will Wilson explores in photographs from his series Connecting the Dots for a Just Transition. In the 1950s, the Atomic Energy Commission began mining uranium on Navajo land. During this time, many townspeople worked in the mines or lived nearby. This led to lifelong health issues and a total disruption of the ecosystems that was exacerbated by a lack of safety information from the American government. As these mines were abandoned, some irradiated materials were used to build homes and other structures, and Navajo people continued to hunt and fish animal populations that were affected by the abandoned mines.

More than 500 abandoned uranium mines remain on Navajo land today, posing a serious threat to the ecosystem and nearby populations. These wounds on the landscapes are presented in Wilson’s series as physical representations of a past some might prefer to forget, allowing viewers to both confront and grieve the true cost of extraction. Wilson’s photographs not only bear witness to these sites and the harm they still pose, but also serve as photographic documentation, which, paired with location data, comprise Reframing Indigenous Remediation—a “platform for voices of resilience, Indigenous knowledge and restorative systems of remediation” on Navajo lands.

The exhibition is a component of the Vanderbilt Eco-Grief Initiative, a multidisciplinary inquiry into the emotions surrounding climate change using the arts as an investigative tool. Along with the exhibition, the initiative will culminate this fall with four newly written short plays commissioned by the Department of Theatre, the Curb Center and the Science Communication Media Collaborative Grand Challenge Initiative. The plays will be produced at Vanderbilt and performed at Neely Auditorium by student actors using sustainable materials and methods. “Each of the plays confronts the issue of eco-grief from a remarkably distinct perspective, demonstrating that grief is not limited only to sadness and despair, but also encompasses nostalgia, joy, curiosity, care and love,” said Leah Lowe, director of the Curb Center and professor of theatre, who will be directing three of the four plays. “With the exhibition, we wanted to highlight what creative inquiry and action might look like when an artist engages with the range of their own climate emotions. The artworks in Extraction/Interaction are beautiful, if somewhat haunting, manifestations of this process.”

Extraction/Interaction will open to the public on Sept. 9 and will remain in place until Dec. 5. The exhibition will be open to the public Monday–Thursday, 10 a.m.–4 p.m. and by appointment, except during Thanksgiving week. Vanderbilt students are invited to visit the exhibition between 3 and 5 p.m. on Sept. 9 for an open house. The plays commissioned as part of the Eco-Grief Performance Project will be performed Sept. 26 through 29 and Oct. 17 through 20. Ticketing information for these performances is forthcoming on the VU Theatre website.