Library conversation Sept. 21 will feature Law School’s Daniel Sharfstein, National Trail of Tears Association’s Tory Wayne Poteete and Oklahoma Historical Society’s Charles Tate

An exhibit currently on display at Vanderbilt’s Central Library explores the lesser-known history of some of the university’s earliest students.

Cherokee and Chickasaw Students at Vanderbilt, 1885–1899 is the result of research led by Daniel Sharfstein, Dick and Martha Lansden Professor of Law, professor of history and co-director of the George Barrett Social Justice Program at Vanderbilt Law School. The exhibit, located in the fourth-floor lobby of Central Library, features archival images, letters, documents, news articles and more.

The project is supported by a Vanderbilt Sesquicentennial Grant, part of the university’s 150th anniversary celebration. Sesquicentennial Grants support activities and projects that engage with the university’s history, look ahead to its future, and explore what makes Vanderbilt distinctive and unique.

Sharfstein said he was inspired to explore this window into Vanderbilt’s past by his Law School colleague, Richelle Acker, associate director of admissions. When Sharfstein was teaching Federal Indian Law in the fall of 2018, Acker mentioned to him that her great-grandfather, Joe Goforth, graduated from the Law School in 1897 and became a Chickasaw judge. Further study of Goforth’s life led to the discovery of a dozen students—eight Chickasaw and four Cherokee—who attended Vanderbilt in the 1880s and 1890s.

“All of them had parents and grandparents who had experienced Indian Removal from the Southeast to Indian Territory, in what’s now Eastern Oklahoma. The loss of ancestral lands was within their living memory,” Sharfstein said.

“I had to wonder: What would it have been like to return to ancestral territory—to travel the Trail of Tears in reverse—to attend this new university? And how did their experiences at Vanderbilt shape their careers and their ability to serve their nations at a time when Congress was moving to destroy tribal self-government? Their story takes place at a formative moment in Vanderbilt’s history and at a crucial moment in the history of Native American sovereignty,” he said.

Raised in Indian Territory, these students graduated from academies established by their nations to educate future leaders. While the Cherokee students found their way to Vanderbilt individually, most of the Chickasaw students came to Nashville as a group, their enrollment funded by a legislative act.

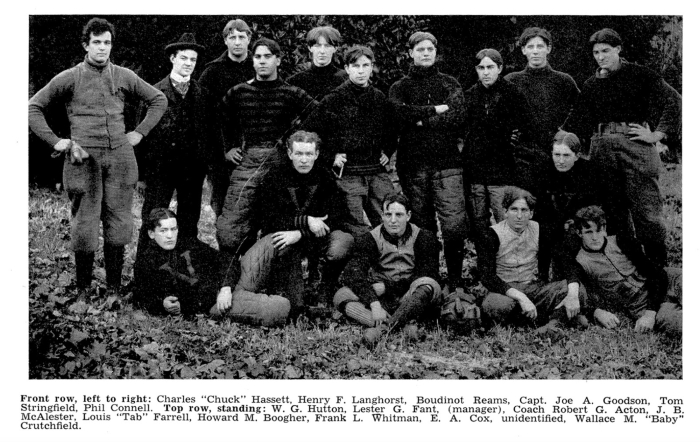

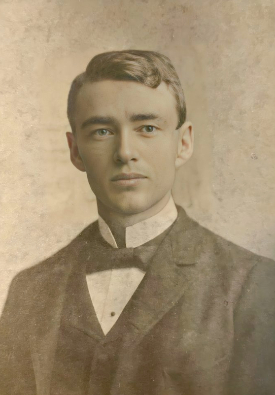

At Vanderbilt, the students immersed themselves in the university’s intellectual and social life, studying history, literature, classical languages, engineering, divinity and law. They lived on campus, served as class officers, were standout athletes on the football and track teams, joined literary societies, participated in Greek life, argued in moot courts and earned prizes for academic performance. When they left Vanderbilt, all returned to Indian Territory.

Back home, the men began distinguished careers in law, business, farming and ministry. Eight became lawyers and shaped tribal affairs from Indian Territory to Washington, D.C.

Sharfstein’s extensive research is drawn from written histories of Vanderbilt University and Law School; biographies of prominent residents of Indian Territory; oral histories left by the Vanderbilt students; press clippings; portions of the Congressional Record; archival materials from the Oklahoma Historical Society, University of Oklahoma and Vanderbilt’s Special Collections and University Archives; artifacts from descendants of the students; and the work of researchers and historians for the Chickasaw Nation.

J. Boudinot Ream, seated, third from left (Vanderbilt University Special Collections)

“As students, they were hardly anonymous and distinguished themselves in all kinds of ways, so Vanderbilt’s yearbooks and the Hustler are valuable sources and all are searchable online, as are Nashville newspapers that covered the university in the 1880s and 1890s,” Sharfstein said.

The research was a deeply collaborative effort, he said. “I had terrific undergraduate and law student research assistants, as well as wonderful partners in the Jean and Alexander Heard Libraries, especially Emily Pavuluri (research services librarian at the Alyne Queener Massey Law Library and lecturer in law) and Kathy Smith (associate director of Special Collections and University Archives),” Sharfstein said. “A law student working on this project, Toni Cross, JD’23, spent her spring break this past year working through archives in Norman and Oklahoma City.”

Sharfstein will discuss the exhibit and the research in two upcoming talks. The first will be on Thursday, Aug. 31, from 5:30 to 7 p.m. in the Central Library Community Room. The second, on Thursday, Sept. 21, is a conversation featuring Tory Wayne Poteete, executive director of the National Trail of Tears Association and former chief justice of the Cherokee Supreme Court, and Charles Tate, a lawyer and former Chickasaw judge who sits on the board of the Oklahoma Historical Society and whose historical research commissioned by the Chickasaw Nation helped create the nation’s archives. The Sept. 21 event will be from 5:30 to 7 p.m. in the Central Library Community Room.

As the Vanderbilt community reflects on its history during this Sesquicentennial year, the early Cherokee and Chickasaw students’ stories are well worth considering, Sharfstein said.

“Although Vanderbilt was built on land claimed by multiple indigenous nations and Nashville was built among Mississippian mounds and was a place where Cherokees passed through on the Trail of Tears, it has been easy to think that our university is a place without an indigenous history,” he said. “After all, Vanderbilt was a racially segregated institution into the 1950s. Yet in the 1880s and 1890s, it welcomed indigenous students who lived in the same dorms as everyone else, ate in the same dining halls, and fully participated in student government, athletics and extracurricular life.

“Vanderbilt was educating indigenous students when it was barely a decade old, and the students who came to Vanderbilt had enormous impact on their nations when they returned to Indian Territory,” he noted. “Vanderbilt was a small school drawing students from a local population, and it’s no exaggeration to say that of our early graduates, Vanderbilt’s indigenous students had some of the biggest impact on the world. Their stories teach us valuable lessons about race, nation and sovereignty.”

Cherokee and Chickasaw Students at Vanderbilt, 1885–1899 will be on display through Sept. 29.

To learn more about Vanderbilt’s yearlong Sesquicentennial celebration, visit vanderbilt.edu/150.