Edited by Seth Robertson

Illustrations by Chris Wormell

In March 1873, Cornelius Vanderbilt and his wife, Frank Armstrong Crawford Vanderbilt, gave a charitable gift that was groundbreaking in every sense of the word. The gift, which officially founded the university that would one day bear their name, enabled Bishop Holland McTyeire to begin laying the foundations for it—literally—by the fall of that year. But the Vanderbilts’ gift was also groundbreaking in that it was visionary.

A “Central University” had long been planned for Nashville by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, but when the Civil War intervened, an entirely new aspiration for the institution emerged. By founding a university in Nashville, a city that recently had experienced the severity of the war firsthand, the Vanderbilts hoped the institution would “contribute to strengthening the ties which should exist between all sections of our common country,” as the Commodore put it—a novel concept in American higher education at the time.

Over the ensuing 150 years, the university has stayed true to its roots by breaking new ground in other ways, whether in its capacity to be a more welcoming and inclusive community, or in its pursuit of discoveries that help answer humanity’s most pressing questions. Here we present an illustrated guide to just a few of the many pioneering figures who have helped Vanderbilt dare to grow throughout its history.

1870s

Cornelius Vanderbilt and Bishop Holland McTyeire

Railroad and shipping magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt and his wife, Frank, gave $1 million to found an “institution of learning of the highest order,” as envisioned by Bishop Holland McTyeire and other leaders in the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. The gift was the Commodore’s only major philanthropy before his death in 1877.

McTyeire, who served as the first chairman of the university’s Board of Trust, chose the site for the campus, supervised the construction of its buildings, personally planted many of the trees that form today’s arboretum and eventually was laid to rest in a small cemetery in an area of campus known as Bishops Common.

At the outset, the university consisted of the Main Building (pictured), an astronomical observatory and residences for professors. The Main Building, which housed all the university’s classrooms and laboratories, as well as a library, museum and chapel, was destroyed in a fire in 1905. It was rebuilt and renamed Kirkland Hall in honor of Chancellor James H. Kirkland.

1890s

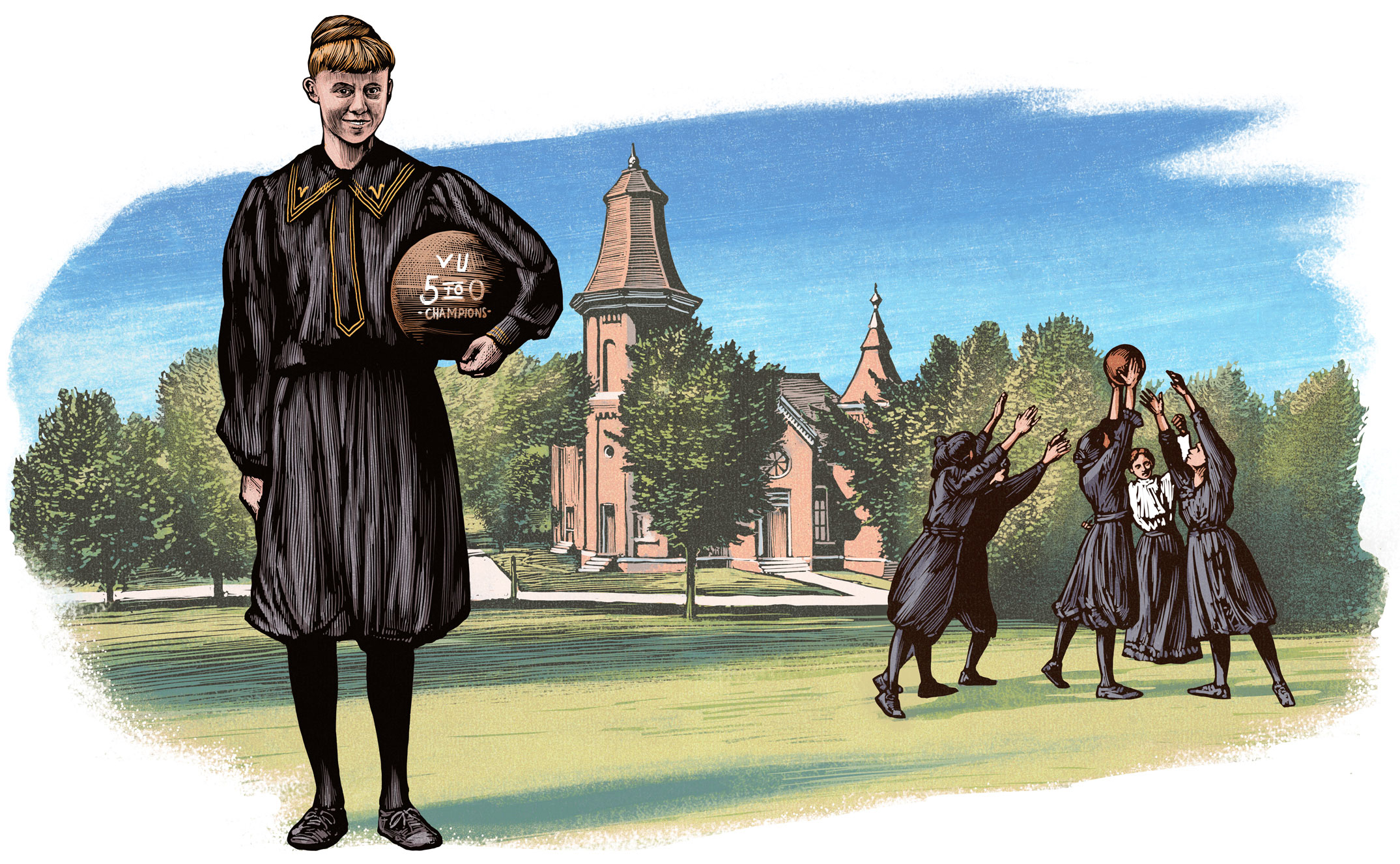

Stella Vaughn, BA 1896

Stella Vaughn, a pioneer in women’s sports at Vanderbilt, had the rare opportunity to grow up on campus thanks to her father, William, who earned an appointment as a professor of mathematics and astronomy. Living in what is now known as the Vaughn Home (pictured below), she entered the university as one of 10 female students in the Academic Department in 1892 and remained on campus after her graduation to teach women’s physical education.

Vaughn formed the university’s first women’s basketball team and served as the coach and captain in 1897 as they played their first game in the Old Gym (pictured), which now houses part of the Office of Undergraduate Admissions. Later she also took on the unofficial role of dean of women students.

“The girls at Vanderbilt have worked against the odds,” Vaughn said, “but they are a ‘plucky bunch’ and not easily discouraged. They have slowly but surely won a place for themselves by their perseverance.”

1920s

Robert Penn Warren, BA’25

After enrolling at Vanderbilt in 1921, Robert Penn Warren became the youngest member of a group of poets at the university known as the Fugitives. Their influential literary magazine, The Fugitive, which was published from 1922 to 1925, helped launch the careers of several prominent writers, including Warren, the only person ever to win Pulitzer Prizes in poetry (twice) and in fiction.

The Fugitives and particularly their offshoot, the Agrarians, of which Warren was also a member, left a complicated legacy, including racist ideas that were prevalent during that era in the South. Later in life, having repudiated those ideas, Warren pivoted toward writing about the injustices of segregation and the rise of the Civil Rights Movement.

“History cannot give us a program for the future,” wrote Warren, the namesake for the university’s Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities located in the Vaughn Home (pictured), “but it can give us a fuller understanding of ourselves, and of our common humanity, so that we can better face the future.”

1950s–60s

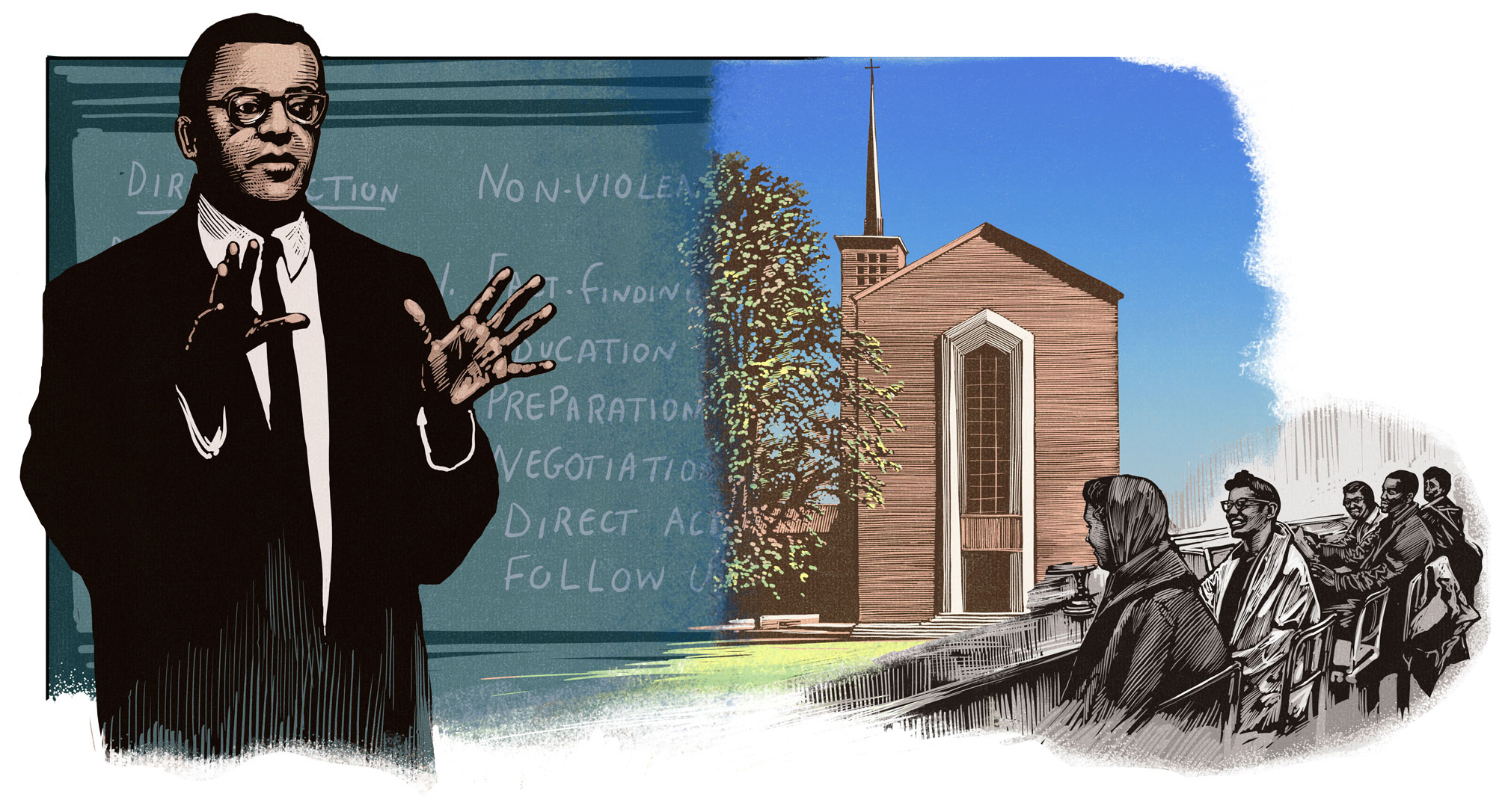

The Rev. James Lawson

A key figure in the Civil Rights Movement, the Rev. James Lawson entered the Divinity School (pictured) as a transfer student in 1958 and soon began leading workshops to teach local college students about strategies for nonviolent resistance.

Out of these workshops arose the Nashville Student Movement, which organized sit-ins at segregated downtown lunch counters in the city and helped lay the groundwork for Freedom Rides throughout the South. Upon learning of his leadership role in organizing the sit-ins, the Board of Trust voted to expel Lawson in 1960. Eventually, he reconciled with Vanderbilt, and the university has since recognized him in multiple ways.

“Hatred can be replaced with love, and violence can be replaced with truth, with beauty, the spirit. I happen to think that can happen,” Lawson said. “We can beat our swords into plowshares, our spears into pruning hooks. Nashville for me is a wonderful illustration of where this happened before and must continue to happen.”

1960s–90s

K.C. Potter, JD’64, and Margaret Cuninggim

K.C. Potter, dean of residential and judicial affairs, emeritus, held several positions during his 30-plus-year career at Vanderbilt, but the common thread throughout was his close work with students. Most notably, he strived to make campus a safe and more welcoming space for all students, including those in the LGBTQI community.

“I treat students just as I would treat any adult,” Potter said upon retiring in 1998. “They are very young, which means their judgment is not so good, but they are people, and they should be treated carefully and respectfully.”

Potter’s friend and colleague Margaret Cuninggim served as Vanderbilt’s fourth dean of women from 1966 to 1973 and dean of student services from 1973 to 1976. With her support, women made significant strides in their efforts for equality at the university. “She made the difference,” Potter said of Cuninggim’s impact. “She became more and more influential, and the men in the administration a little less so.”

In 1988, the Margaret Cuninggim Women’s Center, which occupies the Franklin House (pictured on the left) on West Side Row, was named in her honor. Twenty years later, the cottage next to it, Euclid House, became the K.C. Potter Center, which today houses the Office of LGBTQI Life.

2020s

Candice Storey Lee, BS’00, MEd’02, EdD’12

When Vanderbilt named Candice Storey Lee vice chancellor for athletics and university affairs and athletic director in 2020, she became not only the first woman to hold that role at the university but also the first Black woman to head a Southeastern Conference athletics program. In the three years since, more career milestones have followed.

In 2021, under Lee’s leadership, the university launched the Vandy United Fund, an unprecedented investment of $300 million in Vanderbilt’s athletics programs. Lee also helped broker the university’s first football stadium naming rights and campus collaboration agreement in 2022, which officially changed the name of Vanderbilt Stadium to FirstBank Stadium (pictured).

Across all these initiatives, support for the student-athlete experience has remained paramount for Lee, who is a former captain of the women’s basketball team. “As someone who can personally appreciate the value of Vanderbilt’s unique student-athlete experience,” she said, “I can say without reservation that we are building on a storied legacy of excellence and achievement—in athletics and in academics.”