Photos by Harrison McClary; Text by Bonnie Arant Ertelt

Reading accounts of events through the years is not the only way to learn history. Sometimes history can be held in the palm of your hand.

At Vanderbilt’s Jean and Alexander Heard Libraries, the three-dimensional history of the university is collected and lovingly maintained by the staff of Special Collections and University Archives. Their mission is to “preserve the historical memory of the university”—memory that is found in the objects that, by their survival, attest to a timeline grounded in the space between West End Avenue and 21st Avenue South.

In the 1960s, the Board of Trust mandated that all important records held by university offices were to be saved, so if someone needs to know something like when Peabody began their popular major in human and organizational development, University Archives will have the official documents that codified such changes. Those documents take up 14,000 linear feet in off-campus storage. If that number doesn’t conjure a mental image, University Archivist Kathleen Smith puts it this way: “We like to think of it as that last image in Raiders of the Lost Ark, when you see the Ark of the Covenant being pushed on a cart in a giant warehouse.”

As the popularity of programs like PBS’s Antiques Roadshow demonstrates, objects, when viewed from the distance of time, can serve to start a discussion—not just about nostalgia for what we may remember as a “simpler time,” but about the actual complexity undergirding our history, and how the complexity reflected in the items that surround us may tell a very different story from what we remember. Official documents make a dent in that understanding, but what the staff would love to have more of are artifacts from students, faculty and staff.

“We are always on the lookout for student memories—their letters home, photographs, memorabilia they collected while at Vandy,” Smith says. “Their artifacts—student-produced publications, student organization photos, scrapbooks and minutes. Experiences of the students as they lived their lives on campus are what we need to tell the whole story of Vanderbilt. Vanderbilt’s history is made up of the folks who live it every day.”

Visit vu.edu/special-collections to learn more about items in Special Collections and University Archives and keep reading to find out about some specific items of interest there.

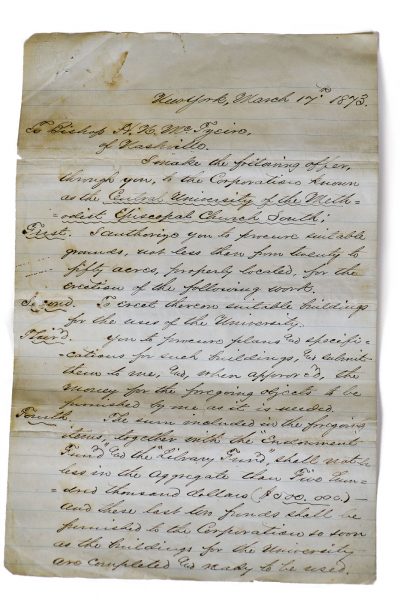

The letter dated March 17, 1873, written by Cornelius Vanderbilt to Bishop Holland McTyeire details one of the two $500,000 gifts made by the Commodore to create a “university to be located at or near Nashville, Tennessee.” The $1 million that Vanderbilt gave to endow and build the university was his only major philanthropy before his death in 1877. Lined paper at that time was primarily used in business correspondence.

The letter dated March 17, 1873, written by Cornelius Vanderbilt to Bishop Holland McTyeire details one of the two $500,000 gifts made by the Commodore to create a “university to be located at or near Nashville, Tennessee.” The $1 million that Vanderbilt gave to endow and build the university was his only major philanthropy before his death in 1877. Lined paper at that time was primarily used in business correspondence.

A doorknob in cast brass possibly was given by the Vanderbilts to Bishop Holland McTyeire in 1875 for use in his home. According to Archivist Kathleen Smith, the Commodore greatly respected McTyeire and wanted to ensure that he had comfortable, even luxurious, living conditions.

A doorknob in cast brass possibly was given by the Vanderbilts to Bishop Holland McTyeire in 1875 for use in his home. According to Archivist Kathleen Smith, the Commodore greatly respected McTyeire and wanted to ensure that he had comfortable, even luxurious, living conditions.

All kinds of ephemera are collected in the University Archives, from buttons, ribbons and cardboard fans (pictured below) to event posters and T-shirts, trophies, mugs and other items most people keep for a short time, then throw out. The library has digitized yearbooks, The Hustler and will soon make available digitized back issues of Vanderbilt Alumnus and Vanderbilt Magazine. Smith says in the next year or so, they hope to have course catalogs for all the colleges digitized, as well as student publications like Versus, Spectrum and many older ones “that reveal what students were thinking at the time.”

This silver pitcher and goblets were used by Martin Luther King Jr. when he spoke in April 1967—less than one year before his death—as part of Vanderbilt’s Impact Symposium. Then in its fourth year, the symposium featured King, poet Allen Ginsberg, civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael and segregationist U.S. Sen. Strom Thurmond, all of whom spoke in Memorial Gymnasium within a 24-hour period.

Commencement now is not all that different from what it was during the university’s early days. Founder’s Medals were given. This one, made by the Nashville jewelry firm of Gates & Pohlman, was awarded to J.C. Reynolds in 1882. Chancellor, deans and faculty wore academic regalia then as now. A mortarboard belonging to Vanderbilt’s second chancellor, James H. Kirkland, who led the university from 1893 to 1937, is included in the University Archives. Today, Black students often wear a stole made of African Kente cloth, like this one from 2012, a tradition that dates back to the mid-1990s, according to AVBA president Myria Carpenter, BS’97.

John Fulton worked at Vanderbilt from 1885 to 1914 as a servant to the famous IV Club—four bachelor professors who lived in Wesley Hall. They were William L. Dudley, Austin H. Merrill, J.T. McGill and W.T. Magruder. James H. Kirkland, who became chancellor in 1893, later joined the group. Before coming to Vanderbilt, Fulton was an enslaved person at Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage. This guitar belonged to Fulton, who often played it for students in his basement room in Wesley Hall.

John Fulton worked at Vanderbilt from 1885 to 1914 as a servant to the famous IV Club—four bachelor professors who lived in Wesley Hall. They were William L. Dudley, Austin H. Merrill, J.T. McGill and W.T. Magruder. James H. Kirkland, who became chancellor in 1893, later joined the group. Before coming to Vanderbilt, Fulton was an enslaved person at Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage. This guitar belonged to Fulton, who often played it for students in his basement room in Wesley Hall.

The Lady of the Bracelet was first awarded in 1928, a tradition that continued until the mid-1970s. According to the 1930 Commodore yearbook, “the choice is based upon scholarship, participation in school activities, personality and general popularity.” The bracelet was passed from one year’s winner to the next and came to Special Collections after the tradition was discontinued.

The Lady of the Bracelet was first awarded in 1928, a tradition that continued until the mid-1970s. According to the 1930 Commodore yearbook, “the choice is based upon scholarship, participation in school activities, personality and general popularity.” The bracelet was passed from one year’s winner to the next and came to Special Collections after the tradition was discontinued.

This gargoyle-shaped downspout was once part of Kirkland Hall, which was rebuilt after the 1905 fire that demolished Old Main.

This gargoyle-shaped downspout was once part of Kirkland Hall, which was rebuilt after the 1905 fire that demolished Old Main.

We don’t know which dormitory this phone was in, but we know that the phone itself wound up in the care of alumnus Clyde Thomas Hines, BA’57, who had a long career with BellSouth Telephone.

We don’t know which dormitory this phone was in, but we know that the phone itself wound up in the care of alumnus Clyde Thomas Hines, BA’57, who had a long career with BellSouth Telephone.

Mr. Hines, now 97, graciously donated the phone to Special Collections. If you recognize it as the phone that used to be in your dorm lobby or hallway, please let us know at vanderbiltmagazine@vanderbilt.edu.

Learn more about Vanderbilt’s first 150 years at vu.edu/150