Research from Associate Professor of Medical and Linguistic Anthropology T.S. Harvey demonstrates how a disease’s name can have a significant impact on the public’s perception, attitude and behavior toward the disease. Disease names should be chosen with careful consideration of the impacts of miscommunication, disinformation and the “infodemic” on public health, he said.

In research recently published in a special issue of Pathogens, Harvey investigates the name COVID-19. The disease was named by the World Health Organization: CO refers to “corona,” VI refers to virus, D refers to disease, and 19 is the detection year.

Naming

Medical communication research shows that when technical terms are used, the public tends to view ailments as more serious. However, the downside of using technical terms—jargon—in public health is that they can be harder to understand. Harvey’s research demonstrates that the disease name COVID-19 constitutes jargon. While it was clear among experts in virology, medicine and public health, it was not fully understood by the public—particularly in early stages of the pandemic. Harvey suggests that the WHO’s official name for the virus, “severe acute respiratory syndrome” (SARS coronavirus 2), as a phrase in its unabbreviated form, does a better job at communicating the public health risk of the disease than the descriptor “COVID-19.”

“As a public health message, the … name ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome’ labels the disease while communicating its virulence (‘severe’ and ‘acute’), warning and alerting the public about the potential symptoms and bodily systems affected (‘respiratory syndrome’),” Harvey writes.

Other disease names in their unabbreviated form perform a similar function, including sexually transmitted disease (STD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), urinary tract infection (UTI), restless leg syndrome (RLS), erectile dysfunction (ED) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“Disease names should be conceived and designed to be comprehensible, intelligible and interpretable to the wider public. Beyond labeling, disease names can perform the critically important function of framing public health messages,” Harvey writes.

Framing

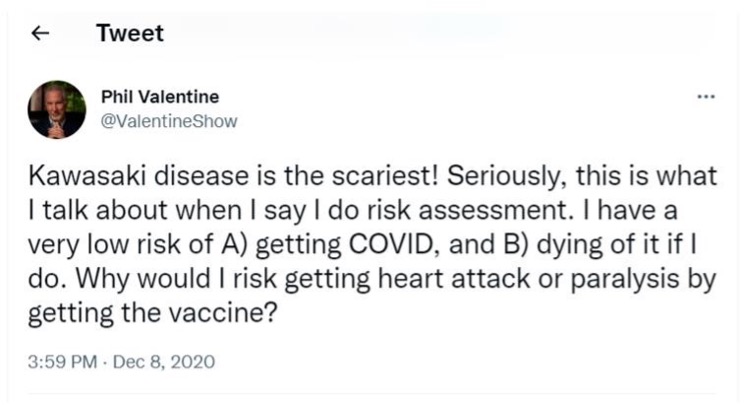

Harvey cites a December 2020 tweet from the nationally syndicated conservative talk radio host Phil Valentine as a cultural example of COVID-19’s “metaphorical framing.” The tweet presents information to influence public perception of risk by conflating the characteristics of Kawasaki disease and COVID-19.

“The resulting juxtaposition of the ‘scariness’ of the exotic-sounding ‘Kawasaki’ disease, mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome, with the implied ‘ordinariness’ of COVID-19 is not only an example of misinformation and xenophobia but ‘communicability,’” Harvey writes.

“[Valentine’s] tweet displays what this study identified as a common skeptical framing of COVID-19, the expression of an outsized (amplified) concern with the health impacts of taking the vaccine and a minimized (attenuated) concern for the potential impacts of contracting the disease and/or following public health guidelines,” Harvey writes. In July 2021, Valentine did contract COVID-19; he died the next month. Near the end of his life, Valentine reversed his position and encouraged listeners to get vaccinated.

Public health and perception

“While the statement ‘COVID is a cold virus’ was misleading and raised serious concerns about the dangers of [lessening] the public’s perception of the risk of COVID-19, based on the CDC’s de facto comparison offered in ‘the basics,’ the claim was not altogether false,” Harvey writes. “More egregious, however, were the kinds of overtly biopolitical interpretations of the COVID-19 acronym circulating within the U.S. during the early days of the pandemic. For example, [there were] public claims that COVID stood for the ‘Certificate of Vaccination Identification’ by Artificial Intelligence or even more problematic and xenophobic, the ‘Chinese Originated Viral Infectious Disease.’”

Outside of acronyms, Harvey cites how using proper nouns to name diseases often has prejudicial undertones. Diseases including the Spanish Flu of 1918 (U.S.), Hong Kong Flu (China), West Nile Virus (Uganda), MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever (named after a river in the Democratic Republic of Congo), Mexican Swine Flu, Avian Flu, and Zika Virus (named after a forest in Uganda) all represent names that legitimize association of “the so-called Third World, its peoples, cultures and places with disease and uncleanliness.”

To address how names influence perception, the WHO issued guidance for naming new diseases in 2015. The guidance aims to mitigate the negative influence of disease names on regional, cultural and ethnic groups. Its effectiveness is up for debate. As the pandemic grew in 2020, the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism found that anti-Asian hate crimes in large U.S. cities increased by 149 percent.

“This is a great example of impactful scholarship because it ties together the local and global. T.S.’ analytical attention to how this virus was framed and named provides an important warning to how we handle future public health concerns. Further, the local-global connections are seen in his examples on what was happening here in our region regarding vaccine misinformation and resistance, as well as global patterns of anti-Asian sentiment that emerged more forcefully during the pandemic,” said Tiffiny Tung, vice provost for undergraduate education and Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Professor of Social and Natural Sciences and professor of anthropology.

Go deeper

The open access article, “COVID-19, Framing and Naming a Pandemic: How What Is Not in a Disease Name May Be More Important than What Is,” was published in a special issue of the journal Pathogens titled “The Ethnographic Study of Infectious Disease Epidemics” in February 2023.

Research was funded in part by a Ford Foundation Senior Fellowship grant.