For Stephanie DeVane-Johnson, the decision to become a nurse was personal. When she was growing up, her mother had health issues, which meant DeVane-Johnson spent a lot of time by her side in the hospital. “I saw the care she received from the nursing staff and that really stuck with me,” she says. “Watching them take such great care of my mom, I knew that’s what I wanted to do.”

Her experience in the undergraduate nursing program at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte helped narrow her focus even more. “I had a professor who was also a nurse-midwife,” she says. “She was amazing and brilliant, and I wanted to be just like her. Her knowledge, skills and compassion for patients and students were like nothing I had ever seen or experienced before.”

DeVane-Johnson entered the Nurse-Midwifery Program at Vanderbilt School of Nursing in 1996 and became a member of the second graduating class. “It was a very new program, and a very small one,” she says.

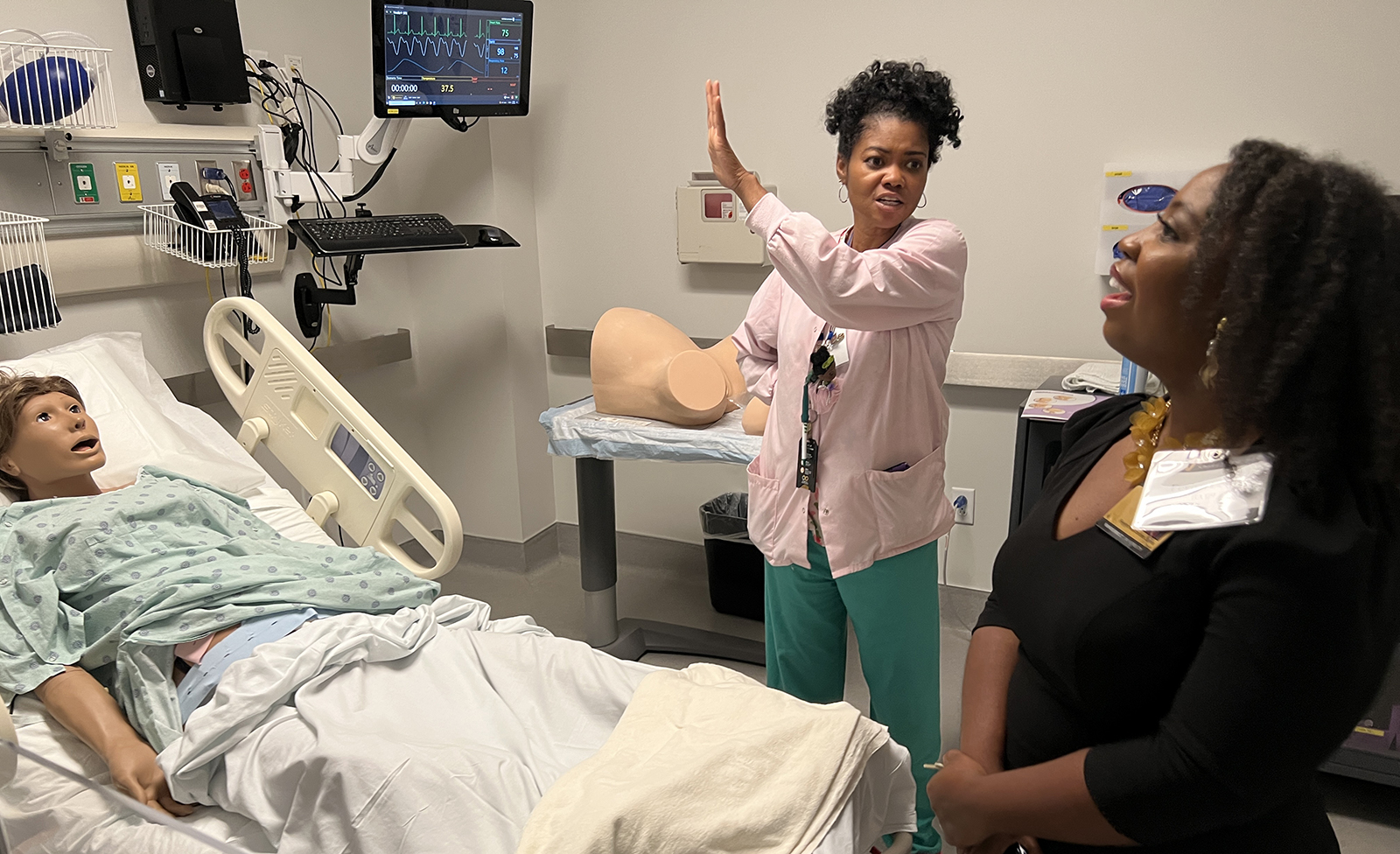

A lot has changed since then. For starters, the annual cohort has more than tripled in size, from eight when DeVane-Johnson was a student to the 30 students the program welcomes today. The faculty is different, too. Notably, it now includes DeVane-Johnson, who joined in 2019 as an associate professor.

“I really didn’t picture myself anywhere else,” she says. “It was truly like coming home. I love teaching at Vanderbilt and being a part of the community from which I was raised.”

As she teaches the next generation of nurse-midwives and serves as a mentor to students of color, she’s also a co-principal investigator on a multiyear community engagement project funded by Duke University, where she previously taught. The project aims to mitigate the Black maternal mortality rate in North Carolina by increasing the number of Black doulas, who provide emotional and physical support as a resource to women in pregnancy, during birth and throughout the postpartum period.

“We need more Black doulas to act as advocates for Black families,” she says. “We’ve created a training program that is comprehensive and culturally tailored, meaning our doula training addresses topics that are unique to the Black lived experience.”

Her doctoral thesis at UNC-Chapel Hill looked at the impact that cultural and socio-historical influences have on infant feeding decisions by Black mothers, a topic she has written about extensively in multiple peer-reviewed journals. “My research explored how the historical aspect of enslaved women serving as wet nurses for their owners’ children and the ‘Mammy’ caricature that emerged later has had a negative effect on the Black breastfeeding rate.”

The grant also addresses the financial barrier—both for doulas in training and the families who want to work with a doula, but cannot afford one. “Everyone benefits from the program,” DeVane-Johnson says. “It’s a win-win.”

The investigation’s findings are preliminary, but they’re promising enough that her goal is to create a similar project in Tennessee.

“Racially concordant care is important,” she says. “And that’s true whether you’re talking about doulas, lactation consultants, nurses, nurse-midwives or physicians. When health care providers look like their patients, have a similar lived experience as their patients, and don’t have cultural biases about their patients, health outcomes improve.”

—Lena Anthony, BS’03