By Andrew Maraniss, BA’92

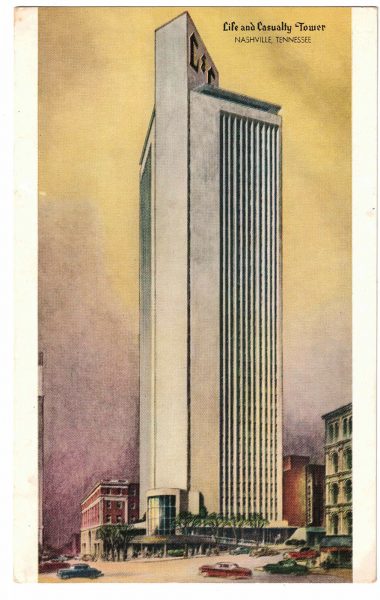

As Nashville has grown dramatically over the past decade, its skyline has become almost unrecognizable to many longtime residents. Yet there stands, alongside the gleaming new skyscrapers, a prominent reminder of the city’s proud past, clad in stately limestone. Though no longer the tallest commercial building in the Southeast, as it was hailed upon its completion in 1957, the L&C Tower—Nashville’s first true skyscraper—remains a striking symbol of the forward-thinking vision the city set for itself generations ago.

It also is a testament to the enduring influence of Edwin Keeble, the designing architect.

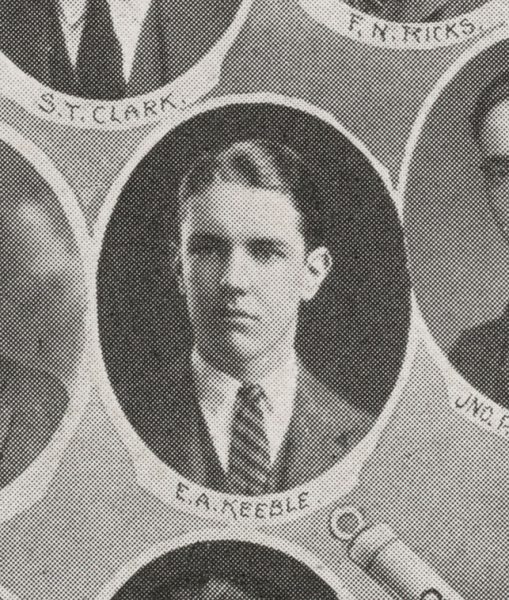

Keeble, who enrolled at Vanderbilt at age 16 and graduated with a bachelor’s in engineering in 1924, was an eclectic and versatile architect—and certainly one of the most prolific in Nashville history. Among his many lasting architectural contributions to the city are Memorial Gymnasium on Vanderbilt’s campus and Hillsboro High School in Green Hills, as well as a number of noteworthy churches, including Westminster Presbyterian, Vine Street Christian and Woodmont Christian—the latter two known affectionately as “Keeble’s needles” because of their soaring steeples. He also designed scores of private homes, which Nashville architect Kem Hinton describes as “miniature masterpieces.”

Keeble became such a well-known and admired figure in Nashville that his work often was treated as front-page news. The April 22, 1959, issue of the Nashville Banner, for example, devoted a bold, eight-column headline to one of his projects. “KEEBLE TO PLAN VA HOSPITAL,” the paper announced.

Before he achieved such stature and cemented his legacy as one of Nashville’s foremost architects, young Keeble found himself at a crossroads. He either could stay within the comfortable confines of the city he’d grown up in or venture to other parts of the globe and widen his worldview. His decision ultimately would have far-reaching consequences—not just for his career and its impact on Nashville, but for something perhaps even more profound in the eyes of every Commodore basketball fan: the curious origins of Memorial Magic.

EDUCATION AND INSPIRATION

Growing up next door to the old governor’s mansion on West End Avenue, Keeble enjoyed a privileged childhood. He attended Montgomery Bell Academy before enrolling at Vanderbilt, where his father, John Bell Keeble, was dean of the Law School.

Early on, Keeble carried a sizable Southern chip on his shoulder as he drove around town in his Jaguar convertible, challenging the notion that the only good American architects—and only worthy projects—could be found on the East Coast.

“There are two kinds of Southerners,” he once said. “The Reconstructed type who thinks everything good comes from out of the East, and those who feel you don’t have to go to New York to get a job done.”

Still, as a young man Keeble came to understand that to gain the best architectural education, he would need to leave his beloved South. After Vanderbilt, he decided to study at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia under Paul Cret, architect of Cincinnati’s Union Terminal, before heading overseas to train at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris.

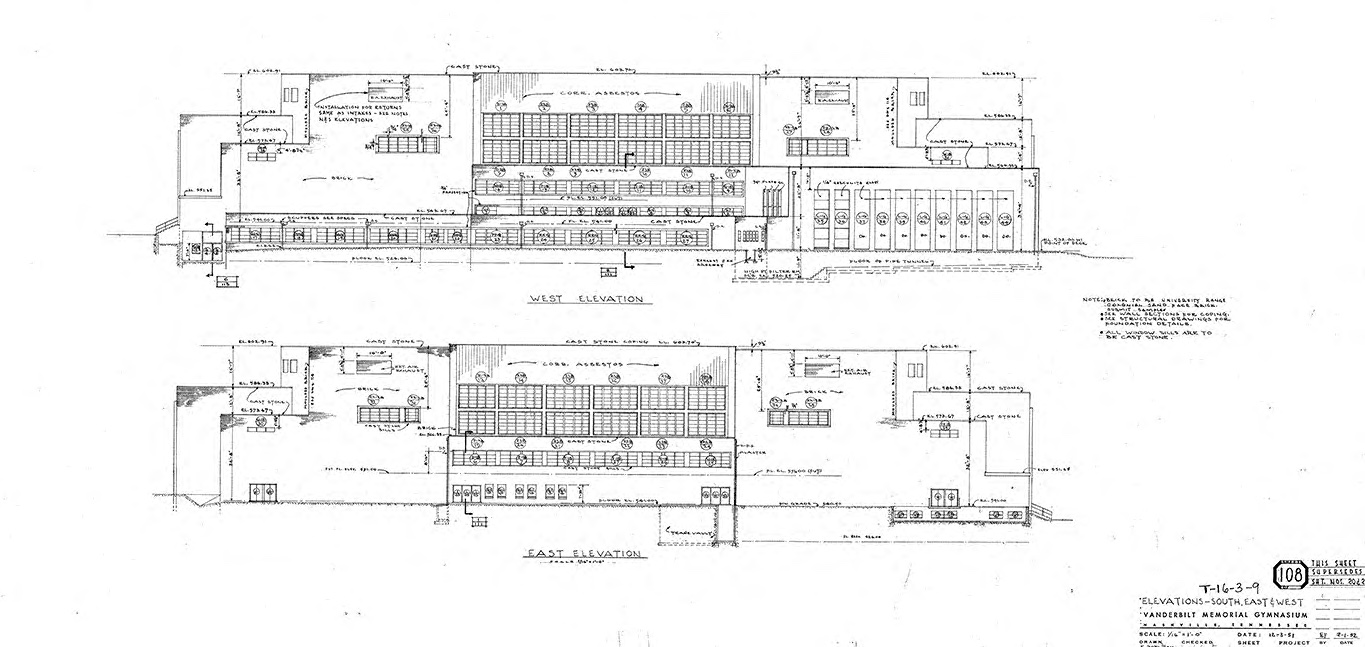

In Europe, Keeble found inspiration for what would become his signature project on Vanderbilt’s campus: Memorial Gym. Playing basketball in the basement of the Paris YMCA, he and others suffered countless bruises and injuries from accidentally running into the brick walls ringing the court.

“The reason we’ve got so much space around the floor in the Vanderbilt gym,” he once told Roy Neel, BA’72, “is that I had learned what it was like running into that wall in Paris.”

Keeble hadn’t set out to design the gym. After returning to Nashville from World War II, he heard Nashville was in the running for a new federal building. He called his old friend Jimmy Stahlman, BA 1919, publisher of the Nashville Banner and member of the Vanderbilt Board of Trust, for advice.

“Forget that one. I’ve got another one for you,” Stahlman told Keeble, according to Neel’s book Dynamite!: 75 Years of Vanderbilt Basketball (1975). “We want to build a fine new facility at Vanderbilt—a memorial to those alumni who died in the war—and I want you to design it.”

After Keeble won the Memorial Gym project, construction began in 1950. Originally designed to hold 6,583 spectators, the gym has since undergone multiple expansions and has more than doubled its seating capacity to 14,316. Despite the renovations, Keeble’s design elements, including a court that sits above portions of the crowd, remain central to the building’s identity, helping to create a unique home-court advantage for the men’s and women’s basketball teams known as Memorial Magic.

Upon the gym’s completion in 1952, Keeble soon embarked on the most ambitious project of his career, the L&C Tower. When opened, the $6.5 million, 495-foot-tall skyscraper was a powerful representation of the city’s confidence and optimism and a notable investment in downtown at a time of suburbanization.

The building was ahead of its time. Vertical fins running the length of the building offered shade from the sun in summer and welcomed its rays in winter—a passive solar design that brought huge savings in energy costs. Speedy modern elevators, detailed woodwork, art deco design elements, an observation deck and exterior lights that changed colors to signal changes in the weather further distinguished it from its contemporary competition. Still, given its Nashville location, the building never quite received its due.

“If it had been built in Chicago or New York,” prominent Nashville architect Earl Swensson once told the Nashville Banner, “it probably would have won all kinds of awards.”

HARMONY AND UNDERSTANDING

As Peter Keeble sat by his dying father’s bedside in September 1979, listening to the elder Keeble discuss architectural projects that he would never see completed, he was reminded of something Edwin had said years earlier.

When asked why he incorporated a particular feature into his church designs—tall windows behind the pulpit that brought nature into the sanctuary—Keeble replied that it was because “God’s out there.” The philosophy was at once a master architect’s display of humility and a testament to his genius.

Keeble saw architecture “as a spiritual thing,” his son recalled. He once traveled the world with his wife to visit divine sites, observing how people, nature and structures interacted in the most serene and hallowed locales.

Keeble also thought that architects had a responsibility not only to their clients but to society at large, whether they were designing a church, a home or an office building. “All buildings,” he said, “should be from pleasant to exciting. Even factories can be interesting and dramatic. Industry does not have to be hideous, nor commerce ugly.”

Humanity, beauty and function should never be sacrificed for supposed efficiency, artificial grandeur or ego, he believed. And he always strove for a balance between intellect and emotion, architecture and engineering, art and technique, religion and science in the work he did.

“Why is it necessary for these causes to reach their catastrophic extremes,” he once wrote, “before people realize that the only cause worth fighting for is harmony and understanding within the extremes; not a listless and impotent harmony, but one as glorious and brilliant many times over as any of the extremes could possibly be?”

Forty-four years after his death, Keeble undoubtedly would be pleased to see that so many of his designs have survived. While his name is no longer as familiar to Nashvillians as it once was, his influence endures all the same. His buildings still surprise, delight and inspire the people who use them, and the principles that defined his life’s work continue to point the way forward for the city he once called home.

Andrew Maraniss is special projects coordinator at Vanderbilt Athletics and a New York Times-bestselling author of five books for teens and adults on the intersection of sports and society, including Strong Inside, a biography of Perry Wallace.