Working people have shaped much of what the United States is known for. Not only have they built America, they have supported the country through its most difficult times—as essential laborers during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated.

Labor Day in 2022 provides a chance to reflect on the past and the future of labor, while examining the economic inequalities that are still prevalent.

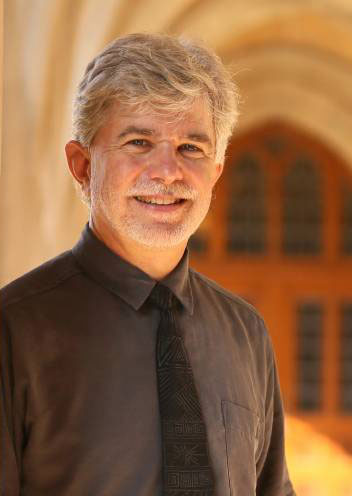

“None of us would be here if it were not for essential labor. And those who appreciate women’s protection at work, the end of child labor, eight-hour workdays, weekends off and benefits should thank working people, whose collective power helped establish these things about 100 years ago—together with faith communities, who used to be much more supportive of labor in the past than they are today,” said Joerg Rieger, Distinguished Professor of Theology, the Cal Turner Chancellor’s Chair of Wesleyan Studies and the founding director of the Wendland-Cook Program in Religion and Justice at Vanderbilt University.

“Perhaps the most important thing to realize is that the concerns of work and labor are not just about the welfare of the working majority. Most people know about that. But they’re also about valuing and appreciating the agency of working people. If essential workers, for instance, are really that essential, this should be reflected not only in wages and benefits, but it should also be reflected in the voice that people have at work.”

Rieger, whose research expertise includes themes related to economic justice, is a contributor to a new series out from the Wendland-Cook Program, Labor Day Reflections 2022: The Divine Urgency of Labor Solidarity. Also, in his recently published book Theology in the Capitalocene: Ecology, Identity, Class, and Solidarity, a chapter is dedicated to the topic of labor and religion and the final chapter deals with the topic of solidarity.

He spoke to MyVU about why economic justice should be a focus of Labor Day.

Q: How does your economic justice research connect to Labor Day?

A: Economic justice is a complex topic, and many people are surprised when they hear that a scholar of religion and theology is investigating it. I do so for two reasons. One is that the United States has the highest Gini coefficient—a number measuring economic inequality—of the world’s advanced economies. In 2022, the Gini coefficient is at 0.485, the highest it has been in half a century, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, meaning that inequality is rampant and on the rise. The other reason is that economic inequality affects not just matters of the economy but also of politics and, most important for my research, religion.

Q: How have faith communities been shaped by inequalities?

A: Faith communities are often shaped by economic inequalities, mostly without being aware of it—for instance, when decisions are determined by the flow of money, which closely parallels the flow of power. Moreover, even religious beliefs, images and symbols tend to be marked by economic inequality, such as when the divine is envisioned in terms of the dominant powers that be—which often happens by default. Workforce and labor issues reflect much of this growing economic inequality—labor relations in other developed countries being less unequal—but they are also the places from which the problem can be addressed. In other words, developing more equal relationships at work impacts not only matters of the economy and politics but also matters of faith and culture, among other things.

Q: Labor Day provides a chance to reflect on workers and the current state of affairs for the workforce. What are some issues we should focus on?

A: Economic inequalities, as they are reflected in current relations of labor and work, are not accidental, and they are certainly not God-given. They are part of economic models that assume that “a rising tide lifts all boats,” as President Kennedy put it in the 1960s. In other words, economies are supposed to benefit most when the largest corporations and stockholders are doing well. Some of these models are currently expanded to include the interest of what is called shareholders in addition to stockholders, especially customers. However, what is still rarely part of these economic models is the interest of workers and employees. In fact, some of these models seem to assume that concern for the interest of workers and employees is bad for business, which is why we are currently seeing tremendous pushback against efforts of workers and employees to organize according to their own interests. The situation at some of the most prominent U.S. corporations like Amazon and Starbucks speaks for itself; they are fighting back hard against workers organizing. Nevertheless, even European corporations such as VW and Mercedes tend to push back against workers organizing in the United States, although their workers are all organized in Europe, where the representatives of the labor unions even have seats and voice on corporate boards.

The study of religion and theology is linked to these questions in interesting ways that are not yet fully understood, and in some cases even actively ignored. If relationships are at the core of human life, fundamental relationships that include relationships at work shape who we are. In other words, unequal relationships anywhere can impact the quality of relationships everywhere. Put positively, if more equal relationships are desirable, for instance in a political democracy (most Americans would agree on this), it might be worth investigating whether more equal relationships should be desirable in other areas as well, including the economy and religion. The relationship between economic, political and religious democracy is one of my areas of interest and a topic we are investigating closely at the Wendland-Cook Program in Religion and Justice at Vanderbilt, which I direct.

Q: One of your books, Unified We Are a Force: How Faith and Labor Can Overcome America’s Inequalities, explores inequities in the workforce and how faith can play a role in solving them. What has changed since you published this work in 2016?

A: Economic inequality in the United States has continued rising for decades. The fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated the problem further—as the wealthiest members of society have benefited disproportionately, others have experienced substantial losses. The old adage that “the rich are getting richer, and the poor are getting poorer” has never been more true. At the same time, the working majority has begun making their voices heard in impressive numbers (after all, 99 percent of the population must work for a living). These voices include not only workers at large corporations but also teachers, nurses and doctors, university faculties, government employees and so on.

Moreover, labor organizing is no longer just a matter of business contracts but includes the welfare of communities and even ecology. When schoolteachers organized, for instance, they were not just looking out for themselves but also for their students and their families, who reciprocated by supporting the teachers in their campaigns. In addition to all of this, the workforce is typically the place of greatest diversity in our society, including people from all races, ethnicities, genders and sexualities. This means that addressing labor inequalities implies addressing and redressing other inequalities of society, as well, and improving relationships across the board. What we also found in the book was that these developments had positive effects on how religious communities operate, and that religious communities that function in more egalitarian ways had positive effects on reshaping relationships at work.