When Chris Webb graduated from Vanderbilt University in 1990, he was not sure how he would use his electrical engineering degree. But after a friend’s accident, the School of Engineering alum found his purpose through the creation of cutting-edge technology that is helping visually impaired people get around independently.

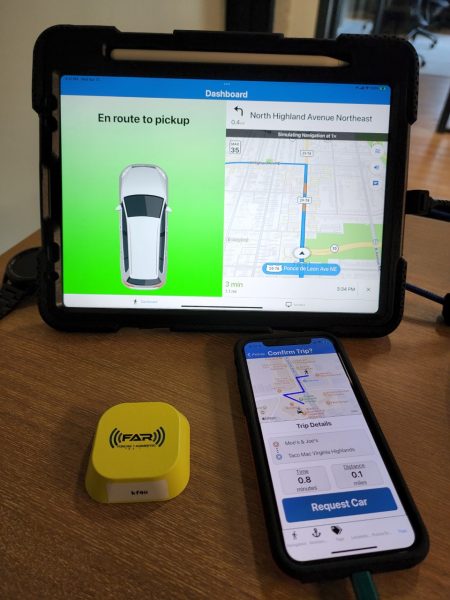

Webb is the CEO/co-founder of Foresight Augmented Reality (FAR) based in Atlanta, Georgia. His system utilizes ultra-wideband technology and audio messages to assist visually impaired individuals with everyday activities such as locating a car, hailing or getting into a rideshare vehicle or arriving at an exact location, like a particular gate at a stadium.

“Too many technologies are developed and then, as an afterthought, they are made accessible to people with disabilities,” says Webb, whose UWB technology was a recent semifinalist in the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Inclusive Design Challenge.

“Things need to be accessible to people with disabilities from the start. That was the point of the challenge.”

After graduating from Vanderbilt, Webb got a job at a company that made pagers and surveillance equipment for the government. He went on to start his own telecommunications company, which he sold in 2001. A couple of years later, he started another telecommunications business, eventually selling his equity in that company as well. But he says it was an accident involving his close friend David Furukawa that led him to what he does now: developing technology that helps people.

Webb says Furukawa suffers from an eye disease called retinitis pigmentosa, which has caused him to completely lose his sight over the years. When Furukawa and his service dog were walking his son to school one day, someone ran a stop sign and struck Furukawa. The service dog managed to push Furukawa’s son out of the path of the car, Webb says, but the dog was hit and eventually died. Furukawa survived with some broken bones.

“I was sitting in the hospital with Dave, and I said to him, ‘We’ve got to do something to help you understand your environment,’” Webb recalls. “So, that’s how we got started.”

Furukawa now is Webb’s business partner at FAR, which has also developed Bluetooth beacons that can be placed in buildings or other locations, like bus stops, to direct visually impaired individuals using audio that’s accessible through a smartphone app.

“We’re giving orientation to where somebody is when they can’t see it themselves,” Webb says. “Once they find that bus stop, they can hear what the next upcoming bus is. If you’re blind, and the bus pulls up, you want to make sure it’s your bus.”

FAR continues to look for ways to help the visually impaired and blind, aging, and cognitively challenged communities by creating technology that’s uniform and easily accessible. Its Foresight Autonomous Vehicle Interface (FAVI) app can control any brand of autonomous vehicle that is linked with FAR’s system, providing a consistent interface whether the rider is summoning their own car or hailing a rideshare.

The FAVI app is also capable of getting someone to a location that does not have a street address or name. For instance, the person goes to a football game at Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta and needs to be dropped off at gate 2. FAR has integrated “what3words” into the app, which allows the user to enter a three-word address that identifies a 3-meter by 3-meter square of planet Earth.

“It will take you right to where you want to be,” Webb says. “Facilities around the world are starting to publish their ‘what3words’ addresses for different entrances.”

Scott Cruce met Webb at an event for the blind and has become a user and tester of FAR’s technology. The 46-year-old says the FAVI app, in particular, is life-changing.

“The fact that you can open that app and use that in conjunction with other GPS software to get right up to where you’re going, this is the best it’s ever been as far as travel for the blind is concerned,” Cruce says.

—Lucas Johnson

To see an example of FAR’s technology, visit FAR UWB Demo – YouTube.