By Melinda Rogers

Illustrations by Nick Ogonosky

As students from Vanderbilt Divinity School file through the metal detectors at Tennessee’s Riverbend Maximum Security Institution, they leave more than just their phones and laptops on the outside. They leave behind any notions of a traditional classroom experience as well.

Carrying only approved writing utensils and notepaper, they report to a classroom that’s a stark contrast to the bright, comfortable ones they’re accustomed to at Vanderbilt. The sparsely decorated walls are painted a drab shade of gray, and prison security guards stand at the ready, keeping watch at all times. Everything about the space feels confining.

Yet perhaps the biggest difference between the Divinity School courses offered on campus and those inside Riverbend—Assistant Professor Graham Reside’s Life on Death Row and Associate Professor Paul Lim’s Justice, Mercy, and Mass Incarceration—are the students’ classmates. Each week over the course of a semester, students explore the issue of incarceration from a theological perspective joined by 14 death row inmates, who at one time in their lives made the costly mistake of crimes for which juries ordered them to pay the price of execution. Vanderbilt has the distinction of being the only university in the country to offer such a course.

Together, the students and inmates discuss how race, class and gender surface in the corrections and punishment system. They explore the many facets of the prison industrial complex and the circumstances behind what some researchers suggest is a cradle-to-prison pipeline: funneling certain populations into the system from one generation to the next. The dynamic of allowing students to hear real talk about life choices and consequences from people publicly deemed some of the state’s most notorious criminals—some whose execution dates could be announced any day—is life-changing.

“How far do we forgive? What does forgiveness mean? When do mercy and justice collide?” asks Reside, who started teaching the class five years ago after developing the concept through his role as executive director of the Cal Turner Program for Moral Leadership in the Professions at the Divinity School.

“It’s easy to say we should forgive one another. But really? Do you want to?”

THE COMPLEXITY OF FORGIVENESS

The juxtaposition of grace and justice is at the heart of the challenging conversations the faculty lead at the prison, which is in the northwest corner of Nashville. Reside, an assistant professor of the practice of ethics, says by the time the semester winds down, most walk away with a sense of shared humanity and an altered view on some of life’s hardest questions. And that’s the point.

Some students walk through the prison doors with staunch views in favor of or against the death penalty. Others are undecided and use the course as a chance to learn more about criminal justice reforms and the policy debates guiding future potential changes. Most wrestle with the humbling realization that inmates painted as monsters by many share human characteristics not unlike their own. Empathy and compassion for survivors of the inmates’ crimes bring another layer of emotional complexity to the classroom equation.

“I tell my students we can learn from the men on death row because their lives are not unlike our own,” Reside says. “They’re struggling with problems of guilt and shame, and we all deal with problems of guilt and shame. They’re figuring out how to live life after they’ve done something wrong.”

It’s easy to say we should forgive one another. But really? Do you want to?

Often the inmates’ candor provides Vanderbilt students with a window into how life experiences shape choices. Most inmates say they regret their crimes, Reside says.

“It’s a weird experience to be sitting two feet away from someone who is awaiting their execution,” he adds. “What you are struck by is their humanity. You’ve got to square who they are in class every week with what they did. But they can’t lie anymore. They’ve been caught. And there’s a type of honesty there that’s refreshing.”

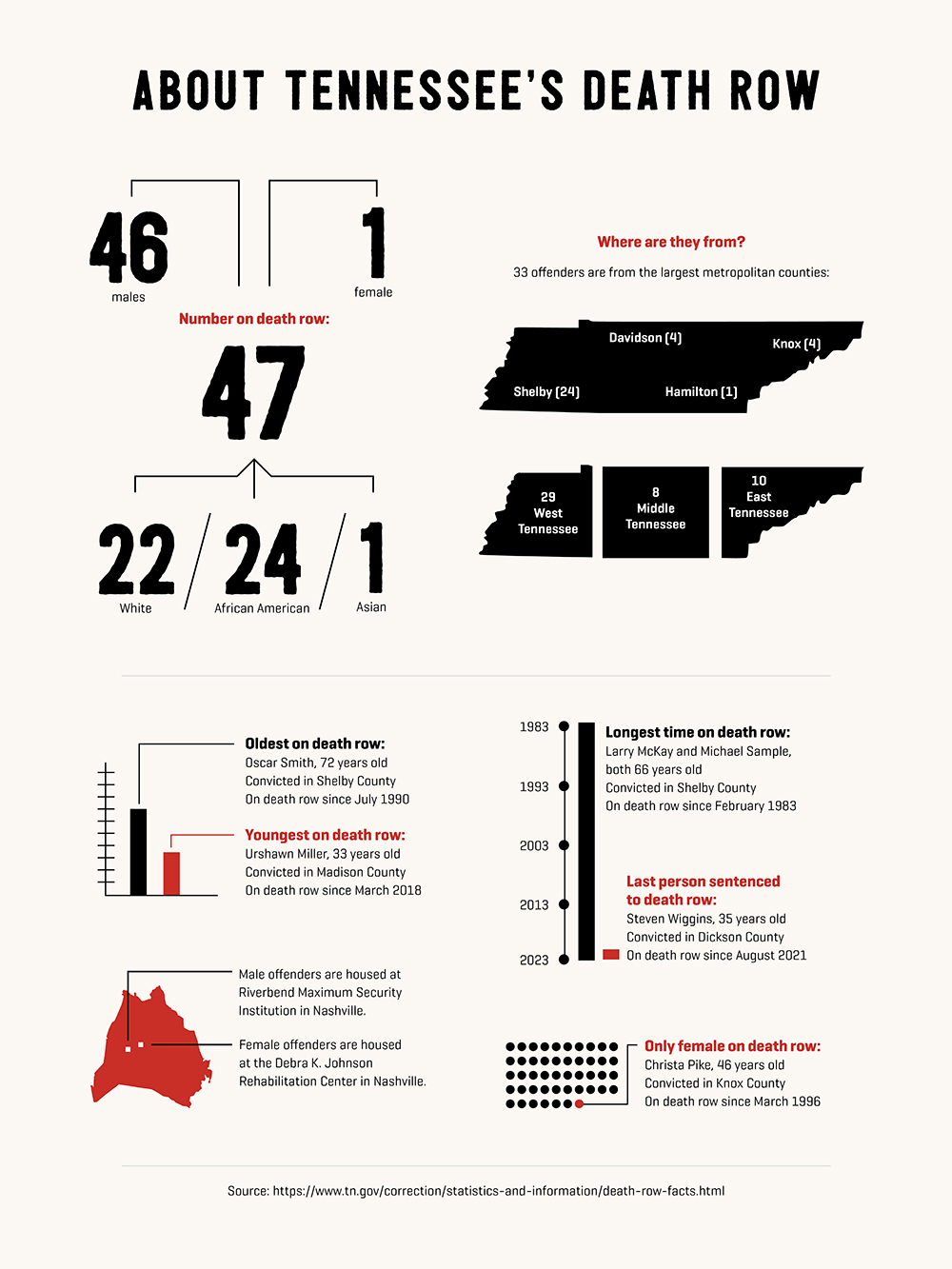

Inmates allowed to participate in the class have qualified for the opportunity after achieving certain security clearances through behavior evaluations. Of the 47 people currently on death row, about 14 usually qualify to engage in the class. Most are “old-timers” who’ve spent years awaiting execution. Engaging with Vanderbilt students about their personal experiences, for some, is part of their own code of restitution for past mistakes, Reside says.

A sociologist and ethicist by training, Reside is mindful that religion doesn’t dominate the conversation. Academic theories around systems that lead to crime and punishment take center stage. Ideas for social change on how to break the cycle are examined.

“They’ve been convicted of egregious crimes,” he says. “We’re not interested in changing them. We are interested in changing the world so more people don’t end up like them.”

Reside is using his teaching experiences as research for a book about forgiveness. The book will explore the topic from all angles, including some who see granting forgiveness as violating justice for those who’ve committed unspeakable atrocities. He knows not everyone sees death row inmates as deserving of mercy, and that’s OK, he says. The hard question of the extent to which forgiveness should apply is something all should think about, he says.

“Human beings hurt each other,” Reside says. “How are we going to respond to hurt, and what are the mechanisms for doing that?

SWEPT UP IN THE SYSTEM

Vanderbilt student Royal Todd grew up in Louisville, Kentucky. Part of his upbringing included time spent visiting family members in prison. Those experiences shaped his career ambitions. After completing an undergraduate degree at the University of Kentucky, he felt called to pursue a master of divinity in Nashville, with hopes to one day work in faith communities.

Reside’s course and the chance to visit death row intrigued him.

He’d read The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Vanderbilt alumna Michelle Alexander, BA’89, as well as John Eason’s Big House on the Prairie: Rise of the Rural Ghetto and Prison Proliferation, before arriving at Riverbend. The chance to apply an academic foundation to real-world situations with inmates pushed Todd to a greater understanding about the outcomes of crime and

punishment.

The sounds and smells of Riverbend also brought him back to childhood prison visits and a realization of troubling racial disparities among those incarcerated across the country.

“The feeling of the first time I went to Riverbend for class was eerily faint and familiar. I’ve had individuals whom I had to go see behind bars,” Todd says. “The fact that statistics show a Black male in the United States has a one in three chance of being a part of this ongoing narrative within the prison industrial complex was never lost on me.

“There are scores of individuals who are swept up in the system and never make it out,” he adds. “Something that never lost its poignancy during the semester is that for every security clearance, as you enter one door, the other door behind you must shut. And so you realize that you are encapsulated as you progress through the security clearance.”

That feeling of isolation gave Todd pause throughout the semester as he interacted with inmates, some whose life stories had shades of his own family history but with a more extreme ending.

Viewing the prison’s execution chamber also left an impression on Todd. Walking out of the prison after class reminded Todd that the inmates who had helped further his study of forgiveness and morality would one day die steps from where those conversations took place.

“What kept me anchored as I went through the course and had these rich conversations was the fact that I could leave,” he says. “The inmates would stay, and I would pass the execution chamber on the way out.”

Currently there are 2 million people incarcerated in prisons and jails in the U.S., with about 2,500 men and women on federal or state death rows, according to the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center. The Sentencing Project, another nonprofit research and advocacy center, has found that Black Americans are incarcerated at nearly five times the rate of white Americans, while Latino Americans are imprisoned at 1.3 times the rate of white Americans. On Tennessee’s death row, nearly half of the current inmates—24 of the 47 total—are Black, and yet only 17 percent of the state’s overall population is African American.

Since the death penalty was reinstated in Tennessee in 1976, the state has executed 13 people. Seven of those executions took place from 2018 to 2020. After a hiatus due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the state announced executions will resume in 2022.

Todd says those he has met in prison will have a lasting impact. Listening to some speak about their darkest chapters and regret may bring hope and inspiration to others who are coming to terms with difficult histories, he says, noting his experiences on death row may weave their way into future ministry work.

“It’s easy to take a glance at death row from the comfort of one’s living room and look at a mug shot and say, ‘This is what they did, and now they are dead,’” Todd says. “But when you’re going to the prison and you’re talking to the person, and they own it and say this is a part of my past from 40 years ago, you mull over questions of to what degree and to what extent is a community satisfied with justice? And to what degree is the community responsible for integrating formerly incarcerated persons back into the communal bond?

“Are we just trying the best we can to dish out to them what we feel like they dished out to us? Or are we trying to better the society as a whole and talk about reconciliation, reintegration and rehabilitation?

A LEADER IN INNOVATIVE CURRICULUM

Paul Lim’s journey to teaching on death row started with his experiences as a child in South Korea. His father was incarcerated as a political prisoner, and he spent third through sixth grades being raised by a single mom, with two siblings, not knowing whether or when his father would be released.

In middle school, after his father’s release from prison, Lim arrived in the U.S. with his family. The transition was rough, and he struggled to belong after immigration to a new home where he didn’t speak the language or understand the culture. The unfairness of what he felt was a forced exit from his homeland stung. He channeled his frustration into a quest for knowledge and went on to graduate from Yale University, Princeton Seminary and the University of Cambridge before joining Vanderbilt’s faculty in 2006.

Now, as an award-winning historian of Reformation and post-Reformation Europe, Lim focuses on themes of freedom found in prison writings and an in-depth study of morality in a course titled Theodicy: God and Human Suffering in Historical Perspectives.

His drive to better understand injustices is rooted in memories. In the years when his father was in prison, the central question to Lim as a 9-year-old was: Why is this happening? It’s a simple question that evolves into more complex academic dissections with inmates and students on several themes related to crime and punishment today, he says.

“I think a lot of students, especially undergrads, have taken this class because they were interested in the subject matter and because of their personal journeys,” says Lim, associate professor of the history of Christianity. “Many of the students are Muslim, Christians or Jewish, and they are interested in the interrelationship between their deity, their own journeys and evil and suffering.

“I always remind the students that we’re going there to learn together,” he adds. “I’m not just there to teach. You’re not just here to learn. The insiders aren’t just there as sponges to soak in everything. We are all engaging in learning together because we’re creating a beautiful community. I think that’s why I continue to teach at the prison.”

Lim and his colleagues view the partnership between the Divinity School and the Tennessee Department of Correction as a mixture of community outreach mission, research collaboration and innovative curriculum experiment. The unusual “open” format of Tennessee’s death row, providing access to inmates who in other states would be separated in lockdown, allows Vanderbilt to offer its unique in-person immersive experience. Vanderbilt also is one of a handful of universities in the U.S. to offer a prison and carceral studies concentration at its divinity school.

The Rev. Emilie M. Townes, dean of the Vanderbilt Divinity School and Distinguished Professor of Womanist Ethics and Society, says the course offerings and experiences on death row show that theological education can—and should—take place beyond the walls of the school. The courses at Riverbend challenge and expand the notion of what constitutes a classroom and encourage a more expansive understanding of who and what a learning community can be, she says.

“The efforts of professors Reside, Lim and others are central to the Divinity School’s commitment to prepare our students for ministry and scholarship in a variety of settings,” Townes says. “Working with the death row community is one example of meeting the needs of our times by combining spiritual and intellectual growth with a sense of social justice and the formation of a new generation of scholars.”

We are all engaging in learning together because we’re creating a beautiful community.

The Rev. Joe Ingle, who has worked for decades to abolish the death penalty and as an advocate for prisoners’ civil rights, has been instrumental in helping Reside, Lim and partners develop their courses for Riverbend. The intensity of trying to find understanding in the difficult details of an inmate’s crime and life journey can be overwhelming at times, Ingle admits. But he says Vanderbilt’s efforts to bring students to prison, and death row in particular, align with a duty to push the younger generation to think hard about current public policy and how they might shape the fate of death row in decades to come.

“What Vanderbilt is doing is hugely important,” Ingle says. “The inmates are teaching us about righteousness and justice and humility. Just from who they are. And that’s a really powerful thing.”