by Mallory McDuff, BS’88

For more than two decades, I’ve raised my daughters, now 22 and 16, in a 900-square-foot rental on the campus of Warren Wilson College, where I teach environmental education in the mountains of Western North Carolina. As a mother and teacher, I couldn’t have anticipated how much my father’s plans for a green burial would shape conversations with my children about life and death, while I was healthy and able to plan.

For more than two decades, I’ve raised my daughters, now 22 and 16, in a 900-square-foot rental on the campus of Warren Wilson College, where I teach environmental education in the mountains of Western North Carolina. As a mother and teacher, I couldn’t have anticipated how much my father’s plans for a green burial would shape conversations with my children about life and death, while I was healthy and able to plan.

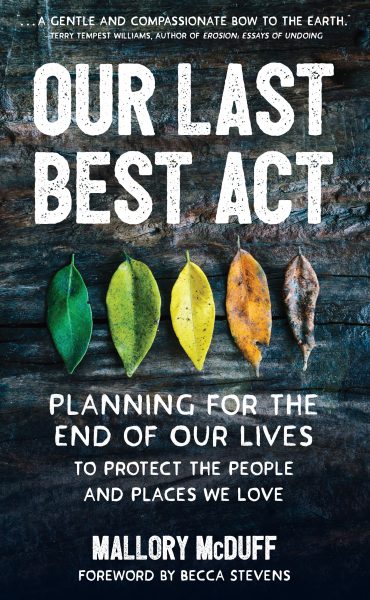

I recently published a book that chronicles my one-year journey to revise my final wishes with climate change and community in mind. The topic of burial is never easy, whether for ourselves or for loved ones. But in my case, this research stemmed from my parents’ sudden deaths—killed in separate cycling accidents two years apart by teen drivers. One month after my mom died at 58, my father shared two pages of directives, although he was in the best shape of his life, having hiked the Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail with my mother.

“I want a funeral that relies on family and friends,” he told us.

His instructions left no room for interpretation: a pine casket, my mother’s linens as a shroud, his bluegrass band at the gravesite and shovels so young and old could close the grave. In my childhood hometown of Fairhope, Alabama, the cemetery didn’t require concrete vaults, and no state requires embalming—two elements of conventional burial that turn cemeteries into landfills underground.

Two years after my mother’s death, the unspeakable happened: My father was killed while biking on the median of the road to the farm where he volunteered in exchange for organic vegetables. To my utter shock—indeed, I screamed the F-word until a student came to check on me—the time had come to use his plan.

My dad wanted what we now call a green or natural burial—without embalming or a vault and with biodegradable materials like a pine casket. In the moment, his words both grounded and propelled me to do the next right thing.

For my own final wishes, I’d chosen flame cremation due to its affordability and convenience, like more than 50 percent of the U.S. population. But as I began to learn about more sustainable choices, I wanted to align my values in life and death, as my father had done.

One year, I volunteered at Carolina Memorial Sanctuary, a conservation burial ground where the land is protected from development through a local land trust. At nearby Western Carolina University, I spent time at a body farm, where I could donate my body for the study of decomposition. Research at this regional university contributed to the science behind human composting, which transforms a body into amended soil. The process is legal in Washington, Oregon, Colorado and Vermont and is likely to expand to other states.

In addition, I interviewed funeral directors about aquamation, a form of cremation using water and lye, available in 20 states, that doesn’t use the fossil fuels needed for flame cremation to burn the body for several hours at 1,600 degrees Fahrenheit. My take-home lesson from this research was that we have more sustainable options for our bodies than we realize and the power to advocate for those choices, even during a pandemic.

Becca Stevens, MDiv’90, co-founder of Larkspur Conservation burial ground located in Westmoreland, Tennessee, writes in the forward to my book: “All justice work is connected. If it is not healing to our bodies, it is not healing to our spirits. If it is not healing to the earth, it is not good for us. This is true in our lives as well as our deaths.”

The end of one individual life won’t shift the climate crisis, but how we care for our bodies after we die can have a collective impact on the climate and our relationship with death itself.

Tending to these matters of life, death and earth may help us carry the people and places we love forever. This was true for me and my parents, and I hope for my daughters and me. These commonalities bind us, as we all become each other’s stories someday.

Mallory McDuff teaches environmental education at Warren Wilson College outside Asheville, North Carolina. She is the author of four books, including Natural Saints: How People of Faith Are Working to Save God’s Earth. Her most recent book is Our Last Best Act: Planning for the End of Our Lives to Protect the People and Places We Love (Broadleaf Books, 2021).