By Graham Hays

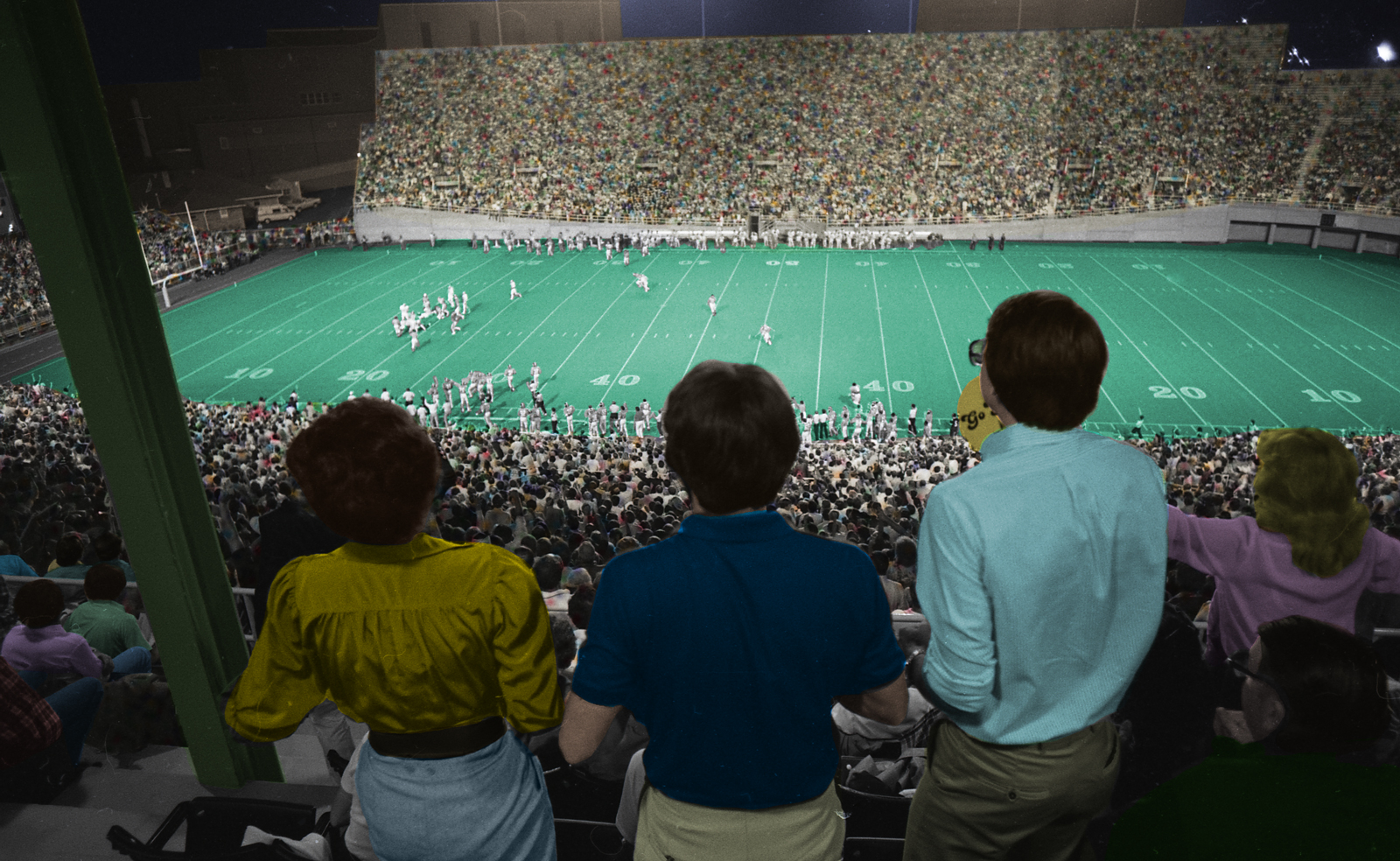

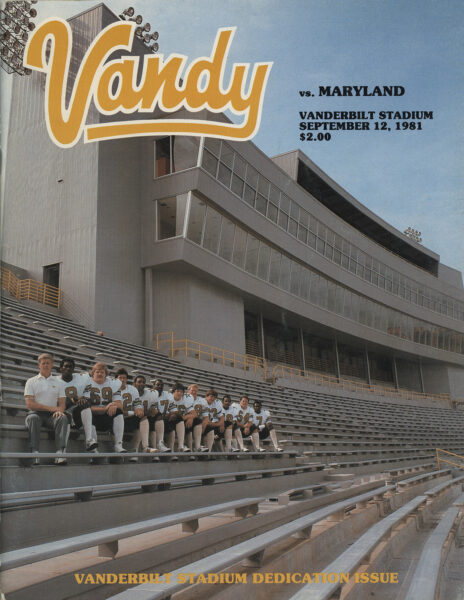

Vanderbilt Stadium roared like never before when Whit Taylor’s touchdown pass to Phil Roach gave the Commodores a lead in the fourth quarter of the opening game of the 1981 football season. A record crowd of nearly 40,000 people in attendance for that first game sent up that raucous cheer, perhaps one of the loudest following a major renovation and expansion of the venue.

The cheers drowned out a sigh of relief from high above the field. Watching from the new three-story press box as a guest of then-athletic director Roy Kramer, Ronald Crutcher, BE’67, was happy that Vanderbilt beat Maryland. But as project manager for the renovations that led to rechristening the former Dudley Field, he was mostly relieved that the stadium was ready.

At least until the lead engineer, a usually stoic figure, turned to him amid the celebratory din.

“All the people were standing up, jumping up and down, and the stadium was really alive,” Crutcher recalls. “He looked at me, straight-faced, and said, ‘You know, I didn’t design this place to carry this much jumping and turmoil.’

“I must have turned white.”

The stadium survived the joke and the celebration. It fulfilled its purpose, as had Dudley Field since another group of Vanderbilt alumni helped build the original venue in 1922. Even now, as Vandy United’s $300 million athletics investment campaign upgrades the stadium and enhances the fan experience, the goal is the same as it was a century ago. From concerts to commencements to presidential speeches, and to football games that still define autumn, the stadium remains a place for the Vanderbilt community to come together and celebrate.

Vanderbilt football was born out of a challenge. The university—as new as the nascent sport itself in 1890—didn’t have a football team when the University of Nashville (later Peabody Normal College) challenged its counterpart to a game. As author Andrew McIlwaine Bell recounts in The Origins of Southern College Football, Vanderbilt students met, agreed to accept the challenge and selected Elliott Jones as their captain and de facto coach, in part because he owned a book about football and had once seen it played in Massachusetts.

With the backing of William Dudley, a chemistry professor and president of the Vanderbilt Athletic Association, the Commodores nevertheless routed their local rivals 40-0 in a game played at Sulphur Dell baseball park.

Having committed to competing in the sport, Vanderbilt sought to excel. Soon its teams played home games where the law school now stands, its field also named in honor of Dudley. In 1910, when news reached campus that Vanderbilt played defending national champion Yale to a 0-0 tie in New Haven, Connecticut, students gathered amid the field’s wood bleachers for an impromptu bonfire—after they marched through Nashville in the middle of the night.

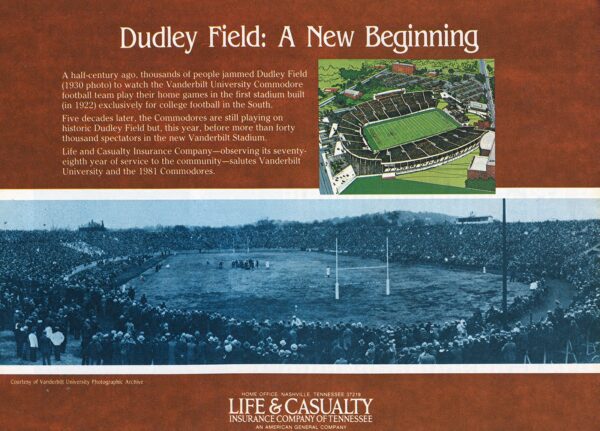

By 1922, in an early example of cultivating the conditions for further success, Vanderbilt committed to building a new stadium on vacant land west of the main campus (purchased by the university more than a decade earlier). Reports at the time estimated the cost of the stadium at around $200,000, shared between Vanderbilt and gifts from donors. More recently in Vanderbilt Football: Tales of Commodores Gridiron History, Bill Traughber estimated the figure at $300,000—the equivalent of several million dollars today.

An article in the 1923 yearbook explains that the new venue retained the name Dudley Field because it was deemed “less pretentious and more modest” than Dudley Stadium—aligning with famous venues of the era such as the University of Pennsylvania’s Franklin Field and Harvard University’s Soldiers Field. The team’s former home was then rechristened Curry Field, in honor of former football standout Irby “Rabbit” Curry, a pilot who died in World War I.

The new Dudley Field opened on Oct. 14, 1922, when Vanderbilt tied Michigan in front of a crowd that included Cornelius Vanderbilt IV, great-great grandson of the university namesake. It accommodated 20,000 fans in its horseshoe-shaped bowl, which did not include any seating on the north end. While it featured a smaller capacity than a handful of stadiums in the Northeast, where the sport was most popular, it was the South’s first football-specific stadium.

By 1960, further expansion of the east side of the stadium added several thousand seats. When President John F. Kennedy visited in 1963 in conjunction with Vanderbilt’s 90th anniversary, more than 30,000 fans filled Dudley Field to hear him speak. Unfortunately, despite a 1974 Peach Bowl appearance that coincided with a young assistant named Bill Parcells joining head coach Steve Sloan’s staff, results didn’t always help fill the seats during football season.

While previous efforts had mostly added to the structure built in 1922, the 1981 renovation marked a complete transformation. In just 212 days, between the final home game of the 1980 season and the 1981 home opener against Maryland, workers replaced all the original concrete, raised the existing steel framework 10 feet in a particularly challenging maneuver and constructed the three-story press box on the stadium’s west side.

As Vanderbilt marks the 100th anniversary of Dudley Field this year, construction related to Vandy United will begin to reimagine the north and south end zones of Vanderbilt Stadium. A new century of football will have a new look, far from the first in the stadium’s evolution.