The effects of racism and sexism lead to higher maternal mortality rates among Black women in the U.S. than previously realized, according to new research from Associate Professor of Sociology and Law Evelyn J. Patterson at Vanderbilt University. Even after controlling for age and women’s reproductive rights support, Patterson and her co-authors found that Black women’s maternal mortality rates were typically nearly double that of white women.

The study, “Gendered Racism on the Body: An Intersectional Approach to Maternal Mortality in the United States,” was published recently in the journal Population Research and Policy Review.

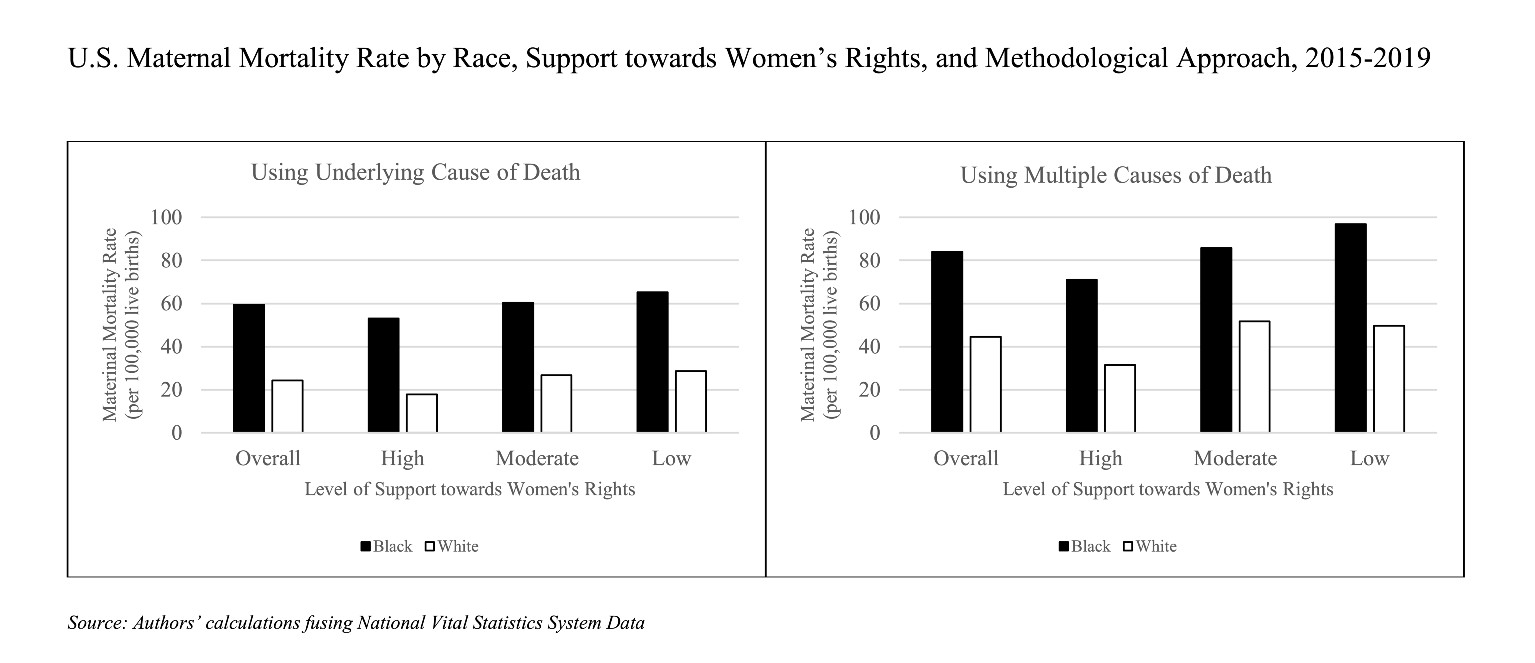

Using data from the National Vital Statistics System, Patterson and her colleagues examined the maternal mortality rates in the U.S. from 2015 to 2019. They measured the rates two ways—using maternal causes as an underlying cause of death and also as one of multiple causes of death. The data revealed a much greater disparity between women of color and white women than had been determined in other studies. Patterson and her team found that maternal mortality rates for Black women in their early 20s are consistent with those of white women in their mid-30s or older.

“Black feminists have done a great deal of work to bring visibility to women of color and the exacerbated burden they carry,” Patterson said. “This study illustrates the ways that some measures of health mask this burden, or rather death penalty, by demonstrating how racism and sexism work together to weaken the likelihood of motherhood not only via infant mortality, but also maternal mortality.”

The team’s research was guided by two overarching concepts: (1) intersectionality—that social categorizations, such as race and gender, create overlapping disadvantages—and (2) weathering—the premature biological aging and associated health risks caused by social adversity. Other research on maternal mortality has examined racial differences but ultimately failed to explain how historical contexts and lived experiences, such as gender and race, affect health outcomes. Patterson said the title of her study—“Gendered racism on the body”—captures the real health risks posed by structural inequality on women in marginalized populations.

“The disparities by race are large and speak to the structural racism and sexism systems in U.S. society,” Patterson said. “We hope to spur new studies considering the methodology and approach we took and believe it is essential to understand the social meanings attached to race and gender and how racialization and sexism negatively affect life outcomes.”