By Michael Blanding

Illustrations by Gary Bates

From the Civil War to the battle over civil rights, the United States has seen levels of conflict in the past that have threatened to tear the country apart. But watching the violent attack on the Capitol building on Jan. 6, 2021, Professor of Political Science John Geer felt like he was witnessing a different kind of political fracturing. The two political parties weren’t disagreeing on matters of policy, but rather disputing the basic facts of whether Joe Biden had won the presidency.

“You can have disagreements, but now we’re disagreeing on what is reality,” says Geer, who is also the Ginny and Conner Searcy Dean of the College of Arts and Science. “The core problem facing the country today isn’t polarization per se. It’s that we are ignoring evidence and making decisions purely based on ideology.”

That realization led to the development of a new undergraduate course at Vanderbilt, co-taught by Geer, historian Jon Meacham and international mediator Samar Ali, BS’03, JD’06. The course, Unity and American Democracy, generated excitement among students ahead of its launch this fall, as hundreds looked to enroll, drawn not just by the reputation of the faculty or the possibility of well-known guest speakers but by the high stakes facing all American citizens. The class asks whether common ground is even possible amid the toxic discourse on both sides of the political spectrum—and what that ultimately means for the future of our democracy.

“We’re living in an hour of great peril for American democracy, and history tells us that we do best as a country when just enough of the citizenry are driven by respect of free speech, for the rule of law, for the position that all are created equal,” says Meacham, who holds the Carolyn T. and Robert M. Rogers Chair in American Presidency. “Unity isn’t about unanimity but about a common acceptance of a social contract that enables the United States to move toward the ‘more perfect Union’ envisioned at the founding of the republic."

DISRUPTING THE CYCLE

Geer and Meacham first began co-teaching six years ago with a course examining the future of the Republican party in the wake of Barack Obama’s reelection. They followed that up with courses on equally hot topics, including the 2016 and 2020 elections. For this year’s class, they recruited Ali, a lawyer and former White House fellow, who co-founded the nonprofit Millions of Conversations to help foster meaningful dialogue among Americans about shared beliefs.

“Americans may be experiencing this level of polarization for the first time in modern history, but the rest of the world is not,” says Ali, who joined Vanderbilt’s faculty as a research professor in political science and law in 2021. “For international relations experts, these aren’t new concepts. What is new is applying them to the American context."

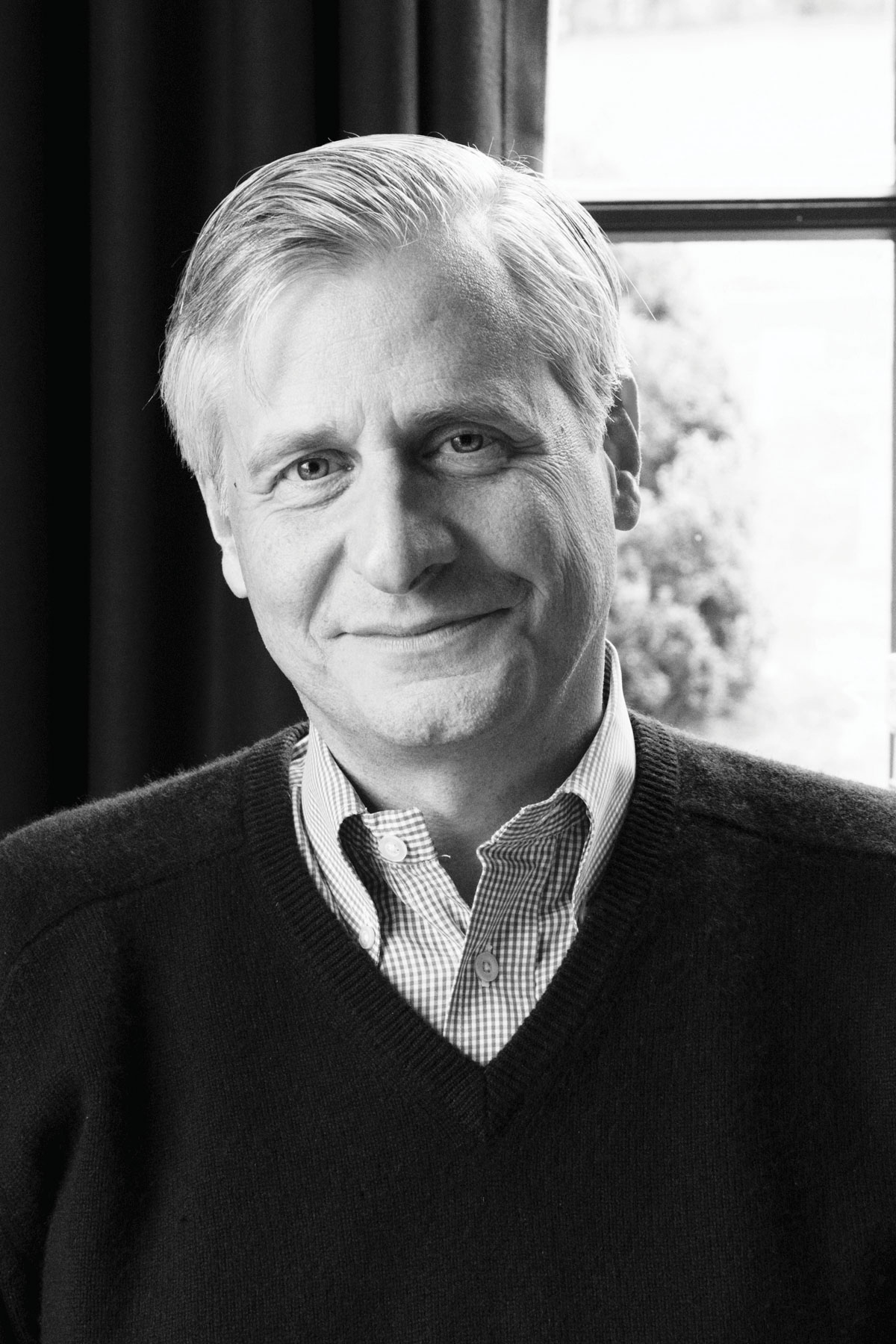

The three different perspectives of the instructors make for a unique collaboration. A Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer, Meacham often employs historical case studies in which leaders such as Abraham Lincoln and Ronald Reagan had to deal with instances of division and crisis. Geer, meanwhile, brings a perspective on how issues such as gerrymandering, money in politics, and the media can affect the political climate.

“I try and give them a theoretical framework by which they can think about under what conditions polarization takes place, and how you might get things to depolarize,” Geer says.

Ali draws on her experience helping mediate international conflict in Syria, South Africa and other world hotspots. Born in Tennessee to Palestinian and Syrian parents, she brings in examples from world conflicts to show how countries fracture along similar lines, starting with animosity on specific issues, which creates fear, which then leads to hate and violence.

“We have to disrupt that cycle,” Ali says. “And how we do it is initially listening to each other, which leads to humanizing each other, and then that leads to empathy and exploration of common values.” While never easy, Ali notes that positive examples of reversing that cycle exist—for example, in Rwanda, which implemented a successful truth and reconciliation commission after a violent civil war. “Rwanda is one of the most peaceful societies in the world today,” Ali says.

Our DNA as a university is very much about unity

UNITY IN VANDERBILT’S DNA

The course is part of a broader initiative called the Vanderbilt Project on Unity and American Democracy, which launched in January 2021. Co-chaired by Meacham, Ali and former Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam, and managed by Geer, the project holds events, conducts research, and publishes articles from an array of thinkers in an effort to cut through political rhetoric with facts and evidence.

Vanderbilt is uniquely suited to hold those conversations, Geer says. Not only did the Commodore found Vanderbilt after the Civil War to heal the wounds between North and South, but also the school’s location as “a blue bubble in the red sea of Tennessee” puts it symbolically in the middle of the country’s divides. “Our DNA as a university is very much about unity,” he says.

In addition to the three professors, the course has added more star power with guest speakers, including New York Times political reporter Jonathan Martin, Harvard history professor Jill Lepore, and authors Annette Gordon-Reed (On Juneteenth) and Sasha Issenberg (The Engagement: America’s Quarter-Century Struggle Over Gay Marriage). The multiplicity of perspectives bearing on such weighty issues has contributed to the course’s popularity with students, say the instructors.

“These students are not interested in narrow disciplinary topics, they want problems to solve,” Geer says, “so when you offer these kinds of ‘big theme’ classes, students react because they care about it.”

By taking such a deep dive into these fractious issues, the instructors hope that students will gain a greater appreciation not only for democracy, but also for the beliefs of those with whom they might disagree. “Our hope is that our great students encounter important and challenging ideas in the class,” Meacham says, “and that they continue to become the kind of engaged and enlightened citizens who see each other not as adversaries, but as neighbors.”