On a Saturday morning in late October, local community members gathered for a remembrance ceremony in Nashville’s Fort Negley Park to read aloud the names of individuals who had once called the area home. Today only vestiges remain of the Bass Street neighborhood, which was founded by formerly enslaved people who had constructed the fort during the Civil War. But time hasn’t diminished its lasting significance as Nashville’s first post-Emancipation free Black community, nor has it erased important clues about the people who once lived there.

Students and professors from Middle Tennessee State and Vanderbilt universities are working together to uncover archaeological details about the once vibrant neighborhood. Currently, the site is being excavated by undergraduate students in a course taught by Andrew R. Wyatt, associate professor of anthropology at MTSU, with support from Vanderbilt faculty.

“It’s an incredibly meaningful site,” says Angela Sutton, MA’09, PhD’14, director of the Fort Negley Descendants Project. “We have been working with descendants and are honored to see them at this dig to hear more remembrances and stories about their ancestors that have been passed down through generations.

“Laws prohibiting the enslaved from reading and writing, alongside historical injustices in document generation and preservation, mean that we now don’t have sufficient written information about this community. The archeological remains of this neighborhood and oral histories of its descendants allow us to get at a fuller and more nuanced story of the ways in which Black people were forced to reconstruct themselves after slavery. This helps us better understand this fraught time period in U.S. history, as well as its modern ramifications.”

The Bass Street neighborhood was settled by formerly enslaved people who had been forcibly collected by the Union Army to build Fort Negley on a hill overlooking Nashville. After defending the fort and surviving the hardships of the Civil War, they remained and built a community at the foot of the hill. However, during the 1950s and ’60s, the historic African American neighborhood was razed for construction of Interstate 65.

“The entire history of Nashville’s African American community is not being told in our city,” said Jeneene Blackman, CEO of the African American Cultural Alliance. “The artifacts discovered are valued treasures for teaching the history of the Bass Street community to future generations. The past belongs to everyone, so these artifacts should be available for public viewing for all to see, to learn, to remember.”

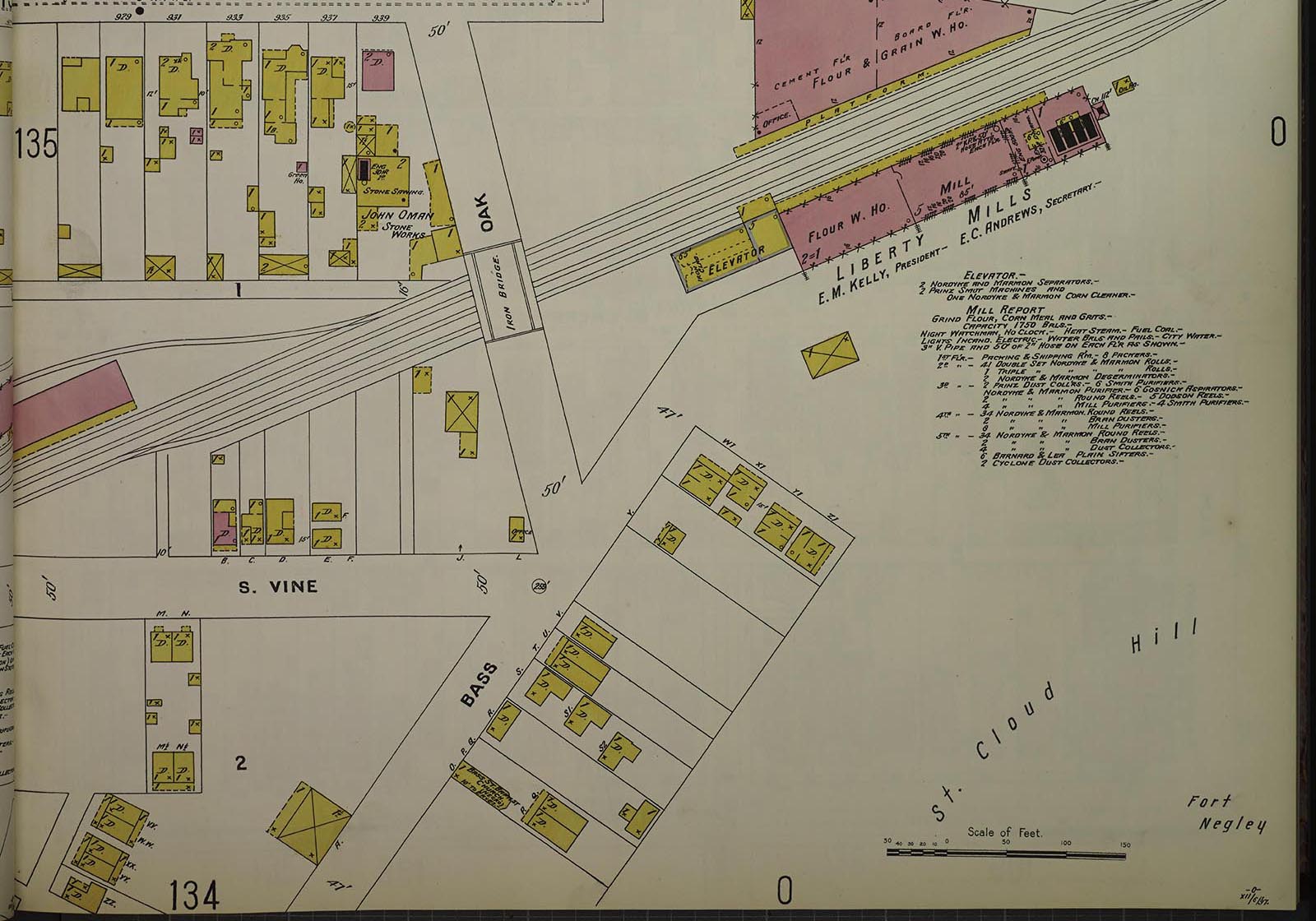

For many years, archaeologists thought that all evidence of the Bass Street community had been damaged or lost. However, recent community interest in the history of Fort Negley sparked attention by researchers at Vanderbilt, Tennessee State University and MTSU. Zada Law, director of the MTSU Geospatial Research Center, was the first to detect foundational evidence of dwellings and a church when she used laser and radar instruments to scan the sub-surface of the fort’s hill.

In 2017, Wyatt secured permission to dig some test pits with his students and invited Sutton to observe. The good news was that the site was not distressed as previously assumed, but almost perfectly preserved. Scans overlaid on maps from just after the Reconstruction era (1863-1877) indicate that the ruins of the original Bass Street Church, a cornerstone of that community, are located on that property.

“The Bass Street community is such an important part of Nashville’s history, and this collaboration between MTSU and Vanderbilt will help in uncovering a part of the past that has been overlooked,” Wyatt said.

Among the Vanderbilt faculty taking part in the dig are Sutton, assistant dean for graduate education and strategic initiatives in the College of Arts and Science; Steven Wernke, associate professor of anthropology and director of the Vanderbilt Initiative for Interdisciplinary Geospatial Research; and Jacob Sauer, PhD’12, senior lecturer of anthropology. Sauer will collaborate on an excavation with Wyatt for a Maymester course this spring with support from Wernke and Natalie Robbins, research analyst in the Spatial Analysis Research Lab.

Meanwhile, Jane Landers, Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Professor of History and a U.S. member of UNESCO’s Slave Route Project, has worked successfully to have Fort Negley designated as a Site of Memory. She was instrumental in helping stop the development of a hotel planned for the site.

“Vanderbilt’s role in early Reconstruction Nashville is fundamental,” Wernke said. “Our university was explicitly part of a larger project of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt to build ties between the North and the South, to begin institution-building in the South after the Civil War.

“The course I have been teaching for the past four years, Archaeological Excavation, focuses on the history of Vanderbilt. It also provides training in archaeological methods on campus, through excavations in front of the servant’s cottage that formerly stood behind the Vaughn Home. I am optimistic that we can use that course as a springboard for Vanderbilt students to work alongside MTSU students in excavations at Fort Negley for years to come.”

–ANN MARIE DEER OWENS