Moments after Vanderbilt defeated Alabama to reach the final of the 2021 SEC Men’s Golf Championship at Sea Island Golf Club in Georgia, Scott Limbaugh served up a seemingly innocuous answer to a question posed in a television interview.

“We liked our matchups a lot,” Vanderbilt’s head coach told the SEC Network reporter. “Felt good about them.”

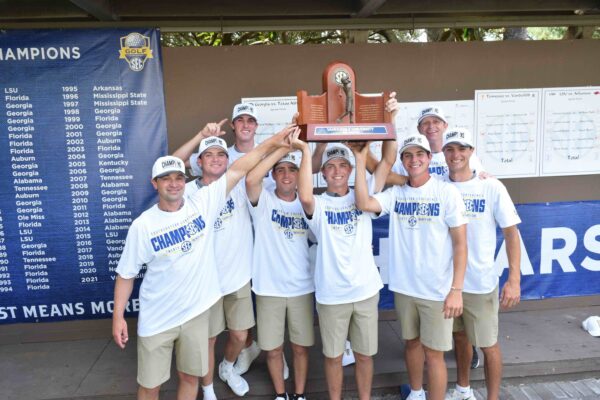

What sounded like boilerplate post-match platitudes had unusual roots. Beating Alabama, and then hours later beating Arkansas for the SEC title, came down to five student-athletes in one-on-one match play format. They hit shots, made putts and handled pressure. They won it.

Limbaugh’s challenge had been to put them in an optimal position to shine. So the golf lifer had turned to a novice to help answer a critical question: Could game theory give the Commodores an advantage in match play lineups?

The Vanderbilt family is teeming with researchers who are well-equipped to help answer Limbaugh’s question, including Eugene Vorobeychik, adjoint associate professor of computer science and computer engineering.

Vorobeychik couldn’t help Limbaugh’s student-athletes read putts or pick the right clubs. But the computational game theorist knew all about optimal matchups.

The Theorist and the Technician

It was an ideal collaboration—two bright minds reaching across professional divides to share ideas. They are also unlikely casting choices for that story.

“I’m just an old country boy from Alabama, and he’s teaching game theory to Vanderbilt students.” Limbaugh laughed. “If I don’t understand something, I just ask old Eugene.”

Growing up in tiny Childersburg, Alabama, at a time when statisticians like Bill James sowed the seeds for the subsequent analytics boom across sports, Limbaugh wasn’t sure what to make of all the numbers. He learned sports from his dad, an old school baseball fan who believed in conventional wisdom like putting down a sacrifice bunt to move a runner into scoring position. The new math turned many such axioms on their ear, arguing, for example, that it is foolish to essentially give away an out with a sacrifice bunt in most situations. Strategy evolved.

Vorobeychik, by contrast, grew up immersed in the new math. He’s also a baseball fan, but the sport’s fertile analytical ground appeals to him as much as cheering for his hometown White Sox. He recently submitted a paper for a conference that examines how pitchers can best sequence pitches during an at-bat, a puzzle he pondered for years while watching games.

What the two have in common, no matter how much Limbaugh plays it off with folksy charm, is relentless inquisitiveness. For people like them, an answer is just an excuse to ask the next question. As Limbaugh rose through the coaching ranks, arriving at Vanderbilt before the 2012 season and quickly assembling golf teams that featured 20 All-Americans, any hesitancy about analytics faded away. He was open to anything that helped his golfers reach their full potential.

He’ll offer a distinctly old school–sounding phrase like “get our expectations down and our discipline up” but back it up by showing student-athletes reams of data on where professional players hit their shots—emphasizing that not even they are as perfect as it seems from afar.

“We’re in a world where data matters,” Limbaugh said. “I’m very aware of that. Any data I can receive, really on anything, I want to be able to get as much data as I can.”

Looking for an Edge

After losing to Stanford in the semifinals of the 2019 NCAA Men’s Golf Championships, Limbaugh believed he could have done more to put student-athletes in positions to succeed in the best-of-five match play format. He just wasn’t sure what that was. Then came a chance conversation that summer with Cardinal coach Conrad Ray, in which his counterpart mentioned seeking advice from Stanford professors whose fields of expertise extended well beyond golf.

With the help of Vanderbilt Associate Athletic Director Alan George, Limbaugh connected with Vorobeychik, whose work applying game theory principles to topics like election security and crime prevention had received national attention. As his baseball fandom attests, Vorobeychik is no stranger to applying his specialty to sports. A high school tennis player, his experience also isn’t entirely theoretical. But as an activity and as research material, golf was new ground for him.

“He has no emotional ties to anything we’re doing, and it’s very hard to find people that don’t have some type of emotional tie to your program.” Limbaugh chuckled. “Any time there’s an emotional tie, they may or may not give you the complete truth. That’s what I love about Eugene. He wasn’t emotionally tied to telling me what he thought I wanted to hear.

“He was just telling me the truth based on science and reasoning.”

Their conversations focused on match play. Familiar to even casual golf fans from high-profile team events like the Ryder Cup and Solheim Cup, match play isn’t complicated. Golfers compete head-to-head. The person who records the best score on a hole “wins” the hole. The match winner is the person who wins the most out of 18 holes (with additional holes if tied).

Professional golf is still dominated by stroke play, in which every golfer competes against every other golfer for the best overall score. But college golf makes greater use of match play; both the SEC and NCAA men’s and women’s tournaments are settled by match-play segments. In last year’s SEC Men’s Championship, Vanderbilt defeated Tennessee in the quarterfinals, Alabama in the semifinals and Arkansas in the final.

To use the SEC final as an example, five Vanderbilt golfers competed against five Arkansas golfers in head-to-head matches. Vanderbilt won the title by winning three of the five matches.

The pairings for each match are determined by the head coaches in what amounts to a draft. The coach of the higher-seeded team selects a golfer from his or her team for the first match. The opposing coach then selects the opponent.

The coaches then reverse roles to determine each successive match. That way, each coach sometimes gets “first pick” for a match.

One variation is that the coach of the higher-seeded team has the option to defer at the start, like a football coach choosing to kick off instead of receive the ball after the coin toss. In this scenario, the opposing coach then selects the first golfer for the first match.

Either way, the format lends itself naturally to game theory and the concept of backward induction.

Within game theory—which is used in everything from business negotiations to international politics—backward induction starts by identifying an optimal result and working backward to achieve that outcome.

Translated into match play, it means Vanderbilt needs to win at least three of five matches.

“You roughly know how they would match up individually,” Vorobeychik said of 10 hypothetical golfers. “What is tricky is how do you maximize the likelihood you’re going to win in the overall matchup, the five-on-five that you’re going to eventually match up?”

Applying Theory on the Course

Vorobeychik acknowledged that detailed predictive analysis would be difficult with even the most pristine data. From weather and course conditions to knowing which five golfers the other team would put forward, there are too many variables to accurately predict exactly how much of a favorite Vanderbilt’s Reid Davenport, for example, might be against a particular Alabama golfer on a given day.

Nothing Vorobeychik and Limbaugh discussed guaranteed success. But both say the approach at least offered a systematic approach to try to tilt the odds in the team’s favor.

They would think through matchups generally, focusing less on individual golfers than on the decision-making process that goes into a lineup.

“The next best thing to data is people’s brains,” Vorobeychik said. “It’s really straightforward to think through this process if you know for sure who is going to win a particular matchup. But obviously you don’t know that. The coach had pretty good intuition about the relative likelihood of who is going to be better in any given match and how uncertain that outcome is.

“A lot of it came down to not just purely game theory or backwards induction, but to using a bunch of intuition that both of us had—me from game theory reasoning and him from the relative matchups.”

What does that look like? In a race to three points, it doesn’t matter if it’s a rout or a nail-biter. Each point is worth the same amount. Feeling confident about as many matches as possible, even if your maximum certainty about any one of them decreases, is a more likely route to three points.

“A lot of my old thinking was about taking the guarantee,” Limbaugh said, referring to the practice of matching a strong player against a much weaker one to guarantee victory. “That’s not really what Eugene thought.”

Similarly, Vorobeychik advised not putting much stock in order of play. That’s counterintuitive in most sports, where the idea of letting your best performer be the one to decide the result at the end is gospel. There is a reason the term “anchor leg” has cultural resonance beyond track and field or swimming. But again, if the objective is winning three out of five points, a point from the second match is just as valuable as a point from the final match.

“It doesn’t mean I won’t ever ask our players for some advice,” Limbaugh said. “But this last year in the SEC Championship, we had a really good sense of what we wanted to do.”

Weather delays forced the SEC to play the semifinals and finals of last April’s tournament on the same day. Vanderbilt had about an hour to prepare for the final match against Arkansas, the defending champion and a team Limbaugh said was full of golfers who thrived in match play conditions. But applying what they took from the discussions with Vorobeychik, Limbaugh and assistant coach Gator Todd had already prepared for every team they might face in the event—including listing two optimal opponents from every team for each Vanderbilt golfer.

When William Moll tapped in for par on the 18th hole, the sophomore playing the anchor leg in his first SEC Championship gave the Commodores their third point and second conference title in the past four tournaments.

‘Moneyball’ for Golf

Maybe game theory had everything to do with the outcome. Maybe it had nothing to do with it. Maybe there wasn’t anything more Limbaugh could have done to help his student-athletes against Stanford in 2019. But innovation rarely happens without experimentation.

“I think it’s really, really cool,” said Vanderbilt women’s golf coach Greg Allen. “That’s all Scott Limbaugh right there, bringing Eugene on board. That’s Scott thinking outside the box and learning from past experiences.”

Limbaugh made sure Allen was included in the early discussions with Vorobeychik. Still, Allen admitted, while he understands the premise and the statistical logic, it is sometimes difficult for him to let go of the emotion that tells coaches to trust their instincts. Limbaugh’s gift may be in marrying the two, old and new school.

Limbaugh’s next opportunity for practical application comes in the inaugural SEC Match Play Championship, beginning this weekend in Birmingham, Alabama. The single-elimination event features all 14 conference teams, with Vanderbilt and Texas A&M the co-No. 1 seeds as reigning division champions. And come next spring, when the SEC Championships and NCAA Tournament roll around, you can bet Limbaugh will call Vorobeychik. He is even hoping they might be able to dig deeper into things like the value of deferring or using the first selection.

Collaboration worked out well once. And the sample size only gets bigger from here.

“I can’t claim any concrete contribution to any particular decision he made because I couldn’t anticipate those situations in advance. He couldn’t either,” Vorobeychik said of the SEC title. “But I thought it was pretty cool. I don’t think my advice made that much difference. I think maybe at the margins. But margins can matter a lot at that level.”

Sometimes they even make movies about winning in those margins.