As the U.S. Supreme Court prepares to decide whether to hear a case challenging the use of race-conscious college admissions, Vanderbilt scholar Joni Hersch says a ban on affirmative action would substantially narrow the pipeline of minorities coming into professional occupations.

In a forthcoming article in the Tulane Law Review, Hersch analyzed data on almost 500,000 college graduates to show a close connection between attending an elite undergraduate institution and the likelihood of earning a professional or graduate degree, which, in turn, is closely linked to gaining employment in influential positions.

“Society as a whole benefits from diverse professionals and leaders,” said Hersch, Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Law and Economics. “Affirmative action supports entry to elite education, which enables underrepresented minorities to reach leadership positions where they can provide services to their communities and challenge policies that perpetuate racism in a variety of industries and professions.”

The case of Students for Fair Admission v. Harvard, which challenges the use of race-conscious affirmative action, is on the U.S. Supreme Court’s list for consideration in its June 10, 2021, conference.

Hersch, who is also a co-founder of Vanderbilt’s JD/PhD joint degree program in law and economics, explained that there are long-lasting societal benefits that result from affirmative action policies in college admissions. By developing a pipeline of future leaders and professionals, there is a greater likelihood that they will advocate for and serve their communities.

Leadership roles in the United States are also disproportionately held by graduates of elite universities, she said, so affirmative action policies regarding admissions play an important role for underrepresented minority students.

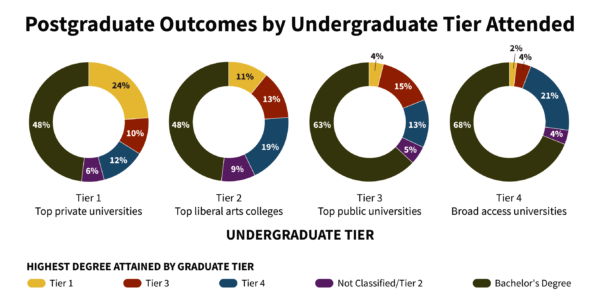

Based on data from the National Survey of College Graduates between 2003 and 2017, only 2 percent of those with a bachelor’s degree from a non-selective Tier 4 institution earn an advanced degree from the most selective private institutions in Tier 1. By contrast, 24 percent of those with an undergraduate degree from a Tier 1 institution go on to receive a graduate or professional degree from a similar Tier 1 university.

Once students graduate from an elite Tier 1 school, race becomes a relatively unimportant predictor of attaining a professional or graduate degree, according to Hersch’s analysis. Further, among students who earn an MD or JD from a Tier 1 institution, there is no difference by race or ethnicity in the probability of being licensed in the profession.

Hersch said these findings indicate that attending an elite undergraduate institution levels the playing field for all races in terms of attaining professional or graduate degrees, regardless of whether affirmative action initially played a role in undergraduate admissions.

“Without a critical mass of undergraduates in the pipeline to earn elite credentials,” Hersch said, “the current underrepresentation of minorities in leadership and professional roles will be further exacerbated.”