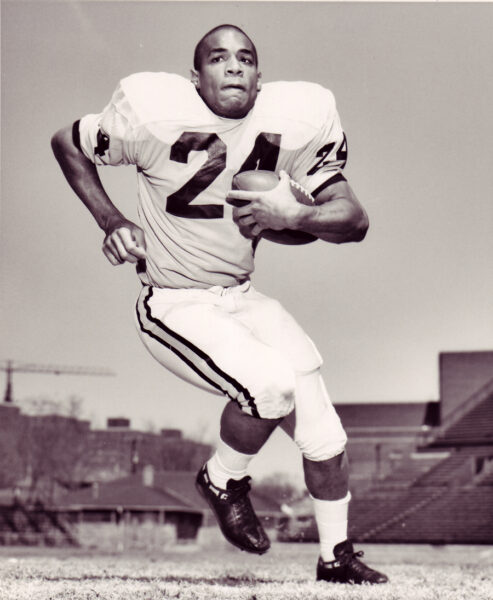

Before he was the first African American from Vanderbilt to play in the National Football League, spending seven seasons with the Baltimore Colts and New York Giants, Doug Nettles was a very bored college cornerback. The frenetic offenses and complex passing games that are commonplace in modern football were no more than distant fantasies 50 years ago.

“Most in the SEC at that time were running wishbone offenses, so there wasn’t a whole lot of throwing back in those days,” Nettles recalled. “The only thing I did was sit out there and run up and down the field with the lone wide receiver all day long, bored out of my mind.”

It was a different world.

As Nettles detailed in the second installment of the Black and Gold Club’s “Conversations with Pioneers” series, that was far from the most consequential way his experiences differed from those of current student-athletes. Conducted remotely, the April 29 conversation with Jim Hurley, Nettles, Walter Overton and Taylor Stokes was part of the Black and Gold Club’s ongoing effort to share the stories of Black student-athletes at the university.

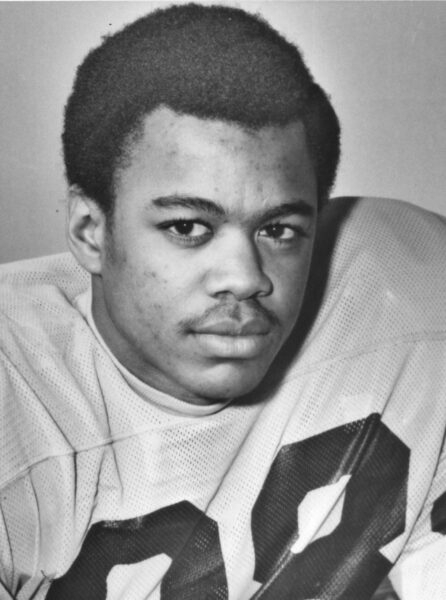

Hurley, Nettles, Overton and Stokes were the first Black student-athletes to play football for Vanderbilt. Stokes and Hurley integrated the program in 1969—Stokes as its first African American scholarship student-athlete, and Hurley after previously integrating the University of Georgia football program. Nettles and Overton arrived in 1970.

Although they came to Vanderbilt only a few years after Perry Wallace and Godfrey Dillard integrated the university’s athletic teams, they didn’t necessarily see themselves as part of a greater movement.

“We had no idea about being pioneers or being the first,” Nettles said. “We were too inundated with trying to survive that whole situation—culturally, academically, educationally and all that kind of stuff. We didn’t really realize what was going on.”

In some cases, it was a parent who encouraged the decision—parents who saw a changing world amid the social upheaval of the 1960s. Nettles’ father pushed him to consider Vanderbilt after they received a copy of a magazine story about Wallace with an ominous anonymous message attached discouraging Nettles from attending the school.

Stokes, too, said his parents were far more intrigued by Vanderbilt than he was initially.

“Part of that vision correlated around creating opportunities for other Black students and Black kids that could possibly maybe come to Vanderbilt because of my efforts,” Stokes said. “The social movement was about Black people elevating themselves in the equality area of education in our society. Moving into spheres that were predominantly white was something that was paramount in our minds in terms of Black elevation.”

The candid conversation on April 29 detailed how the Vanderbilt they experienced 50 years ago was far from immune to the problems of the time and place it inhabited.

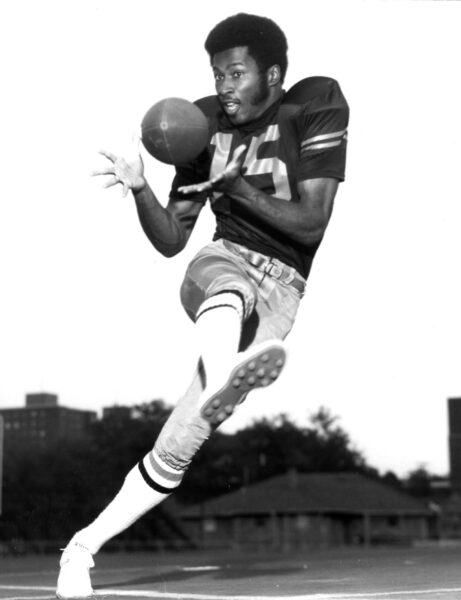

A decorated high school quarterback, Overton recalled asking the Vanderbilt coaching staff if he would be allowed to play that position if he signed with the Commodores—a couple of years before Tennessee’s Condredge Holloway became the SEC’s first Black starting quarterback. Overton said he was assured he would have the opportunity, yet after leading the Vanderbilt freshman team to some success, he found himself behind his freshman backup on the varsity depth chart the next season. Coaches told him they wanted him to play other positions.

“I left the school, came home and I pouted with my mom and my friends,” Overton recalled. “They said, ‘It’s not all about football. It’s about getting your education and growing up and being a man.’ So I stayed. With bitterness. But I tried to make the best of it. With what I’ve done and what has happened here in the present, probably one of the best decisions I ever made was coming to Vanderbilt.”

Unable to find consistent time on the field as a receiver—unfairly, as he saw it—Stokes became a kicker.

“We’re probably the best pass combination that never got to play at Vanderbilt. In practice and whatnot, we’d eat them up,” Stokes recalled of his partnership with Overton. “A lot of times, you just have to deal with the situation you’re dealt.”

The four former teammates recalled conversations among themselves at the time about whether to stay or leave en masse in reaction to the injustices they encountered. Stokes ultimately withdrew from the university in 1971 before returning—at Overton’s urging—to earn his bachelor of arts degree with an interdisciplinary major focusing on race, culture and religion in 2009.

Stokes recalled attending the 2008 Music City Bowl while completing his degree and watching Vanderbilt beat Boston College for the program’s first bowl win in decades. But it wasn’t the success that struck him most—or even the offenses that he would have loved to play in as a receiver. What struck him was the presence of so many young Black men on the sideline.

“Pioneers don’t often get to share in the spoils of their efforts,” Stokes said.

In a wide-ranging discussion that lasted more than an hour, the former teammates didn’t try to soften the stories of the difficulties they encountered five decades ago. They didn’t hide the pain they felt at the time—and even subsequently. And their unflinching honesty offered a reminder that as much as Vanderbilt needed their voices as students, it still needs those voices as alumni.

“It is astonishing what we all have talked about and how all of us have come together and all of us have had our internal problems,” Overton said. “But as we find out, we are people that have substance. We know how to make things work.

“I’m so proud of the guys that are with us today, we’re still together. Being with the university is a part of making this university what it should be.”

Jim Hurley resides in Nashville and has enjoyed a long career with Kroger.

Doug Nettles resides in California and is a former teacher and coach.

Walter Overton resides in Nashville and recently retired as general manager of Nissan Stadium.

After withdrawing from Vanderbilt in 1971 to take over the family painting and contracting business, Taylor Stokes went on to a successful business career. He resides in Pleasant View, Tennessee.

For more information, visit the Black and Gold Club.