A Vanderbilt University School of Medicine student-led effort has led to Dixie Place, the city street that runs between Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Central Garage and the Oxford House on 21st Avenue South, being renamed Vivien Thomas Way.

A brief program will be held Monday, April 5, at 1 p.m. to unveil the new street sign. The event will be livestreamed so that those who wish to attend the event can do so virtually.

A Nashville native, Thomas secured a job as a laboratory assistant in 1930 with Dr. Alfred Blalock at Vanderbilt University; was tutored in anatomy and physiology by Blalock and his research fellow, Dr. Joseph Beard; and rapidly mastered complex surgical techniques and research methodology. Due to the institutional racism at the time, Thomas was classified and paid as a janitor despite that fact that by the mid-1930s, he was doing the work of a postdoctoral researcher in Blalock’s lab. Thomas’ work led to a number of life-saving surgical techniques, though he was not credited for his role at the time.

“We commend the student-led effort to rename the city street in honor of Dr. Vivien Thomas. He was an individual who, despite institutional racism, made invaluable contributions to medical research that saved thousands of lives and advanced the field of cardiac surgery. The previous street name evoked a painful history in our country—one that is in stark contrast to Vanderbilt University’s vision for the future and efforts to foster an inclusive environment for our Black community,” said Dr. André L. Churchwell, vice chancellor for equity, diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer for Vanderbilt University, who also serves in a similar role at VUMC.

“We commend the student-led effort to rename the city street in honor of Dr. Vivien Thomas. He was an individual who, despite institutional racism, made invaluable contributions to medical research that saved thousands of lives and advanced the field of cardiac surgery.”

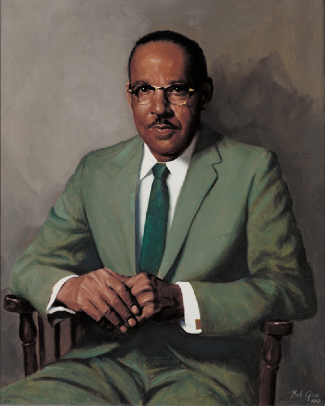

–Dr. André L. Churchwell

“While we have made great progress and undertaken the work of confronting racism in Vanderbilt’s own past, we recognize there is significant work yet to be done,” Churchwell said. “We will continue to invest resources and time into ensuring a welcoming, nurturing and robustly inclusive community for all who study, learn, teach, research and work here.”

The process to change the name of Dixie Place was born of discussions that current second-year medical students had with their advisory college mentors during summer 2020, when they, along with the rest of the country, witnessed widespread civil unrest after the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis last May. Many expressed a desire to help effect change.

Advisory mentor Walter Clair, professor of medicine and executive director and chief medical officer for the Vanderbilt Heart and Vascular Institute, encouraged them to think about how they could merge what they were doing as medical students with their desire to influence positive change without disrupting their educational journey.

“I suggested to them, ‘If you want to do something, I have been driving to Vanderbilt and parking in Central Garage for years; I come down 21st Avenue, and the last stoplight I have to get through is where one takes a left on Dixie Place to get to the garage. If you want to do something, change the name of that sign!’” Clair said.

The students liked the idea and formed a committee to explore options for renaming the street, with the support of Medical School Dean and Vanderbilt University Medical Center President and CEO Dr. Jeffrey Balser and input from Clair, Churchwell, Matt Scanlan, senior director of VUMC’s Office of State Government and Community Affairs, Consuelo Wilkins, vice president for health equity at VUMC, and VUMC Chief Operating Officer John Manning.

As part of this process, Vanderbilt University Medical Center did its due diligence regarding the history of Dixie Place. The origin of the street name is unclear. Dixie Place was part of the subdivision developed between 1897 and 1907 by real estate developer George W. Shields (1860-1922) that was formerly part of a larger tract of land given to John Cockrill in 1784 for his service to the state of North Carolina in the American Revolution.

To choose the street’s new name, students organized a collective effort among representatives from the African American, Latinx, Pride and Veteran employee resource groups, the Minority Housestaff for Academic and Medical Achievement, faculty advisers, deans and administrators to develop key values and principles that guided the nomination process.

“We appreciated the opportunity to remove this daily reminder of the Confederacy and racism from our medical campus. We recognized that as students, our time at Vanderbilt may be transient, and we wanted to ensure that the voices of others who have worked at Vanderbilt long before us and may remain long after us were included in making this change,” said second-year medical student Alex Lupi.

The students presented their top choices to Manning, who worked with Balser to ultimately choose to rename the street in honor of Thomas.

After an approval process involving the Metro Nashville Government, the Metro Council officially approved renaming the street on a third and final reading on Dec. 1. Delays related to the pandemic pushed back production of the sign, which was originally anticipated to be installed in late December or early January.

Thomas’ history with Vanderbilt and his contributions to cardiac surgery are well documented.

Blalock and Thomas began experimental work in vascular and cardiac surgery, and when Blalock was offered the position of chief of surgery at Johns Hopkins University in 1941, he insisted that Thomas accompany him. Thomas was charged with the task of creating a “blue baby”–like condition (cyanosis) in a dog, then correcting the condition by means of the pulmonary-to-subclavian anastomosis. In 1944, Thomas stood on a step stool behind Blalock, coaching him through the first such procedure in a human.

“As an aspiring surgeon, the story of Vivien Thomas is a major inspiration for me,” said second-year medical student Kayvon Sharif. “That he became a pioneer of cardiac surgery—even with no formal medical degree and despite the constant obstacle of racism—demonstrates an ingenuity, perseverance and excellence that is rarely seen. By renaming Dixie Place in honor of him, we can recognize a truly exceptional figure in Vanderbilt’s history. This street sign at the entrance of our medical campus will bear the name of a man who will serve as a source of pride to students, faculty, staff and patients for years to come.”

Clair agreed the student-led social justice effort will stand the test of time.

“Our students are only going to be with us for four to five years, but they will be alumni for decades. Won’t it be nice for them to come back to their 10th or 25th Vanderbilt Reunion with their children and grandchildren and point to the street sign and say, ‘See that sign over there? It used to be called Dixie Place, but we changed that. Let me tell you how.’”