Growing up, Rebecca VanDiver, assistant professor of history of art, spent afternoons in her father’s custom framing shop, running between rows of molding. With one parent in the framing business and the other working in elementary school education, VanDiver jokes that she was “predestined” to become an art historian.

VanDiver focuses her research on African American artists—particularly Black female artists of the 20th century. In the classroom, she presents art history not only as a discipline that allows for a study of the history of artistic movements and style, but also as a lens to study culture and history. She argues that all academic discourse, including that of scholars, should be scrutinized.

“I want students to understand that the scholarship we read is a frame,” she says. “It’s one way of telling this story, and there are many other ways to tell it.” This reframing is particularly significant when bringing more marginalized voices to the table.

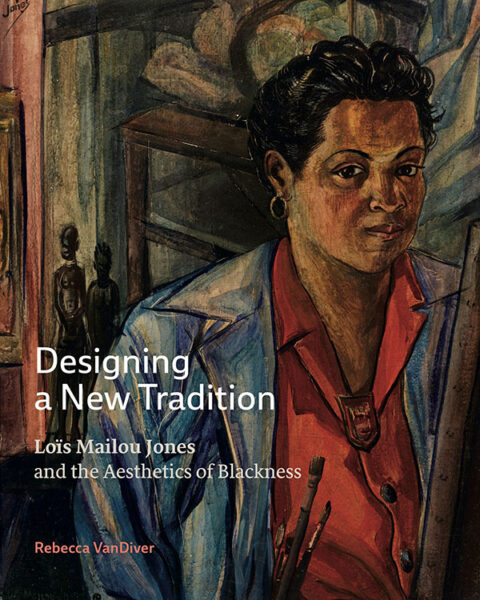

Her recently published book, Designing a New Tradition: Loïs Mailou Jones and the Aesthetics of Blackness (Penn State University Press, 2020), shines a light on an unseen artist and corner of American art history. “Loïs Mailou Jones was desperately in need of a single artist monograph,” VanDiver says. “I’m just so happy it’s in the world.”

Her recently published book, Designing a New Tradition: Loïs Mailou Jones and the Aesthetics of Blackness (Penn State University Press, 2020), shines a light on an unseen artist and corner of American art history. “Loïs Mailou Jones was desperately in need of a single artist monograph,” VanDiver says. “I’m just so happy it’s in the world.”

These days, VanDiver is excited to think more thematically and to engage with multiple artists. Her current book project, which is provisionally titled States of Emergency: Politics and Ephemerality in African American Art, 1965-2015, examines how African American artists deploy ephemerality as an artistic strategy. VanDiver describes the project as one way to “think about how African American visual artists are engaging with the idea of ephemerality. Are they creating ephemeral objects? Are they manipulating ephemera into their practice? Are they responding to ephemera in their work in different ways?” She cites the initial inspiration for the project as Kara Walker’s exhibition After the Deluge, which went up in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. VanDiver was fascinated by Walker’s response to the event.

“Her artistic strategy was to counter the constantly changing news cycle,” VanDiver says. Instead of creating new Katrina-inspired art in the show, Walker used her own “historical” artworks and those culled from the Met’s collection. “It was to point us back to all the artworks highlighting the continual, ongoing struggle of African Americans and point out that this is not new. This has always been happening.”

VanDiver wanted to see where else this was happening in the art world. Now, as a Mellon Faculty Fellow at Vanderbilt’s Center for Digital Humanities, she is excited to explore the archives.

“I like finding holes in it,” she says. “My hope is that I’ll uncover some new artist or exhibition, not necessarily for me to study, but for others in the field to take up.”

—Carla Diaz, MFA’19