To most modern listeners, Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony no. 9 From the New World is a mainstay of the classical music repertoire. Its evocations of folk melodies, particularly the plaintive English horn solo in the second movement, and themes that preview some of Aaron Copland’s 20th century ballet music sound familiar. Yet those who heard it at its 1893 premiere found it confusing: Was it American music? Was it Celtic? Bohemian?

To most modern listeners, Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony no. 9 From the New World is a mainstay of the classical music repertoire. Its evocations of folk melodies, particularly the plaintive English horn solo in the second movement, and themes that preview some of Aaron Copland’s 20th century ballet music sound familiar. Yet those who heard it at its 1893 premiere found it confusing: Was it American music? Was it Celtic? Bohemian?

Douglas Shadle, associate professor of musicology, explores in his recent research how the drive for a classical music style that reflected an American identity was led by a European with radical ideas about basing it on African American folk music. His book Antonín Dvořák’s New World Symphony, released Feb. 26 by Oxford University Press, argues that, at the time, Dvořák’s symphony raised new questions in classical music about the place of African American music within the broader musical culture of the United States.

A “national” style of music

Questions about what constituted a “national” music style had been percolating since the end of the Civil War. Shadle’s previous research, documented in Orchestrating the Nation (Oxford University Press, 2015), explored 19th-century symphonies by American composers that created diverse, but competing, views of American identity. Few of these pieces are known—much less programmed—today.

“White American musicians had a deep European inferiority complex that said European music was the gold standard,” Shadle said. “On the one hand, they felt that the European classical tradition was universal, but at the same time, they wanted a national brand within that universal umbrella. How to achieve that was one of the driving questions of American composers throughout the 19th century.”

In 1892, Dvořák—a Czech composer relatively well known in Europe—entered the conversation. Upon coming to the United States that year to take directorship of the National Conservatory of Music, he was asked if an American national music style was achievable. He said no. However, in the ensuing months, Dvořák heard African American folk music for the first time. Feeling that a truly musical expression of the American people through their folk music could somehow imbue his own creative work with the same identity, he suggested that these songs could serve as the basis for an American national music.

“We think of classical music as somehow standing outside history and time in that it transports us to another world,” Shadle said. “However, in the months leading up to the creation of the New World Symphony, one of the chief discourses outside of classical music in the early Jim Crow era was the status of African Americans as full citizens and participants within American society. Dvořák’s own relationship to African American and indigenous American music became embedded in New World Symphony, but his understanding of the music was in many ways deeply flawed.”

Lessons learned from the past

With his advocacy of African American and indigenous themes, Dvořák essentially gave authority to white composers to freely appropriate Black music. Shadle’s book notes the ways in which composers, critics and even Dvořák’s students at the National Conservatory eventually held up the New World Symphony as a new standard for an “American” national style—a standard that Black musicians and composers did not accept as the one for which they were striving.

“In some cases, Black intellectuals and musicians were appreciative of Dvořák for introducing these ideas,” Shadle said, “but at the same time felt that he was woefully incapable of executing his own vision musically because he didn’t understand the emotional impact—the human narratives—behind the spirituals, for instance.”

Holding the New World Symphony up as the American standard exposed deep misunderstandings about Black musical creativity that are still prevalent in classical music. Shadle’s book illustrates the numerous ways in which white individuals in positions of power in classical music have attempted to box in the activities and creative expression of people of African descent.

“This is still present in the classical music industry,” Shadle said, “in the sense that Black composers working today are often judged critically by writers or audiences on the extent to which their music conforms to stereotypes of what Black music should be.

“What my research attempts to do is open up the importance of lesser-known stories and voices from the past,” Shadle said. “Looking at these issues historically opens a fresh window for understanding the present. The challenge facing contemporary ensembles, particularly post-COVID-19 and after last summer’s protests, is how to reboot classical programming more equitably. Expanding one’s frame for what’s possible must include allowing and enabling people of different backgrounds to share their own stories, to be part of that conversation, rather than having programming determined from above by a limited number of stakeholders.”

“What my research attempts to do is open up the importance of lesser-known stories and voices from the past,” Shadle said. “Looking at these issues historically opens a fresh window for understanding the present. The challenge facing contemporary ensembles, particularly post-COVID-19 and after last summer’s protests, is how to reboot classical programming more equitably. Expanding one’s frame for what’s possible must include allowing and enabling people of different backgrounds to share their own stories, to be part of that conversation, rather than having programming determined from above by a limited number of stakeholders.”

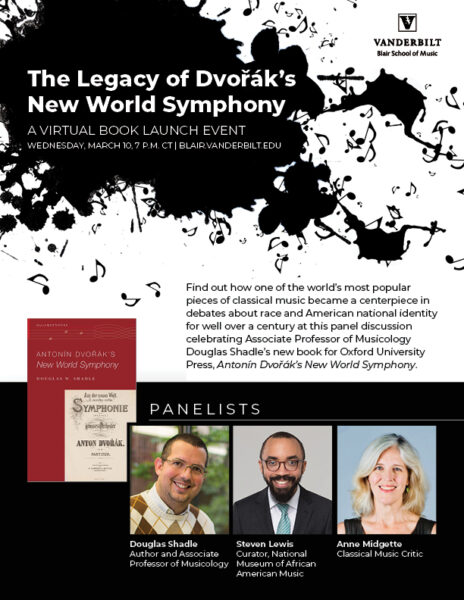

Vanderbilt Blair School of Music and the National Museum of African American Music will hold a virtual book launch and panel discussion on March 10 at 7 p.m. CT, which will be viewable from the Blair livestreaming page. Panelists for the program, along with Shadle, will include Steven Lewis, curator and musicologist with NMAAM, and Anne Midgette, music journalist and former classical music critic at The Washington Post.