By John Pitcher with additional reporting by Kristin Whittlesey

Tucker Biddlecombe never dreamed during his many years of music study that one day his chosen profession would be considered among the most potentially dangerous. Yet, as director of choral activities at Vanderbilt University Blair School of Music, Biddlecombe has had to learn how to cope with the uniquely hazardous risks associated with COVID-19 and singing.

“Everybody is at risk with this virus, but choral groups are especially vulnerable,” Biddlecombe says. “Some of the first deaths from COVID-19 resulted from a choir rehearsal in Washington state, and we now know that the virus is easily transmitted during singing. We figured out pretty quickly that we were going to have to do things differently if we were to continue making music.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the entire Vanderbilt community to change its routines. But because of the live-performance nature of music schools, the Blair School has implemented numerous precautions to ensure that faculty and students remain safe—all while maintaining a semblance of the highly personalized instruction for which Blair is known.

To ensure that Blair could provide in-person classes this fall, the school had to go beyond Vanderbilt’s campuswide guidelines and institute numerous safety protocols based on research from the University of Colorado-Boulder. That study, commissioned by a group of more than 120 performing arts organizations, examined how vocalists and woodwind and brass players might transmit the virus through aerosol emissions—and what steps could be taken to prevent the spread in musical settings.

Getting Vanderbilt Blair’s various large ensembles back into action took a little more ingenuity. The school no longer could fill its concert halls with audience members, and even assembling musicians in large groups to rehearse proved problematic. So, faculty and students made use of the latest software and video technology to pivot from the big stage to the small screen, and in the end potentially broaden their audiences.

Follow the science

Lorenzo F. Candelaria, who began his tenure as the Martha Rivers Ingram Dean of the Vanderbilt Blair School in July, wasted no time instituting a policy of “rigorous caution.” That meant following the science, being persistent and “never letting our guard down,” Candelaria says. “Our goal was to get through the entire fall semester with the students on campus, meeting in person with their teachers. It’s been hard work, but we’re still meeting in person and have had no incidents that can be traced to the school.”

That kind of diligence begins in the music studios of professors like Jeremy Wilson, a trombonist who chairs Blair’s brass department. Wilson is no stranger to hard work. At age 25, he successfully auditioned for the world-renowned Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and its sister organization, the Vienna State Opera—posts that required him to learn vast amounts of repertoire on the tightest deadlines while meeting the most exacting standards. For Wilson, now 38, navigating the internationally competitive world of classical music proved to be almost easy compared to coping with COVID-19.

“Teaching in the middle of a pandemic is far and above the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” Wilson says. “My students and I have basically had to change the way we do everything.”

For Wilson and his students, change begins with the most effective tool that science has provided so far to combat COVID-19: rapid testing. All voice, brass and woodwind faculty now undergo weekly testing for the virus. All Vanderbilt Blair undergraduate students are tested twice a week this spring, as are all Vanderbilt undergraduates. Once cleared for the week’s instruction, the faculty and students enter into a kind of musical bubble.

Before the pandemic, Wilson liked to get up close to his students while they played so he could watch their every move. The closer the better, Wilson says, to make sure they didn’t slip into bad habits.

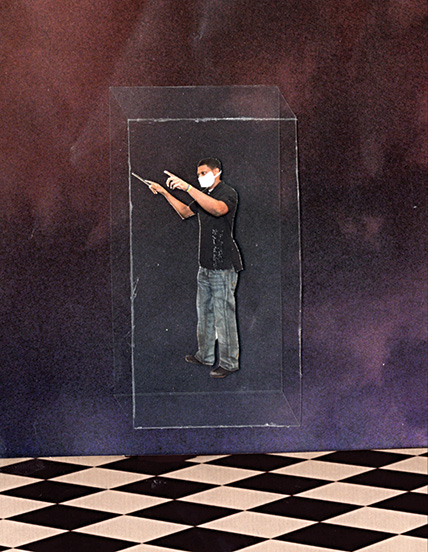

That’s all changed. Wilson’s studio now includes a glass partition that separates him from students by a distance of about 15 feet—which is farther than the guidelines from the University of Colorado study. Like nearly everywhere on campus, masks are mandatory, even on the trombones themselves. All brass players affix bell covers to their instruments to limit potential aerosol spread. Moreover, students come to their lessons with two masks, a regular one when they enter the studio, and one with a slit cut into it so they can still play while masked. One more safety item many students and faculty probably never imagined they would need: puppy pads, large absorbent mats normally used to house-train puppies. These turn out to be ideal for absorbing any moisture—spit—that builds up in their instruments.

Mastering the use of video conference technology for music instruction took more work. While remote learning works well for big lectures, it posed numerous problems for musicians. Faculty and students suddenly found themselves held hostage to their broadband services. Wilson says different download speeds made sustained trombone notes sound like a train whistle getting closer one moment and fading into the distance the next. The videoconference software also interpreted sustained trombone notes as ambient noise and automatically reduced the volume.

For some, remote learning encouraged some productive experimentation. Robert Wake, a senior majoring in trombone performance, says he began recording practice sessions to send to Wilson last spring when all Vanderbilt classes went virtual. “The feedback I got from that has really improved my playing,” Wake says.

Wilson noted that other students also began recording their sessions, a development he hopes will continue in his post-pandemic studio. “I love it when students record their practice sessions,” Wilson says. “It allows me to be a fly on the wall and get a sense of how well they use their time.”

Bridget Conley, a senior majoring in tuba performance, says there have been upsides to learning in the pandemic. On the one hand, Conley says she’s had more time to experiment and take risks. On the other, she says “I’m focusing more on the basics, and I’m already reaping the benefits.”

Technology recreates the stage

While digital technology functioned primarily as a learning tool for some at Blair, for the school’s large vocal and instrumental ensembles like the Vanderbilt University Singers, Vanderbilt Opera Theatre and Vanderbilt Wind Symphony, and for signature faculty ensembles like the Blair String Quartet and other professional recitals, technology has become more of a canvas. The school has had to reimagine its live-performance environments for a world that can only gather virtually for now.

For Concert Series events and student recitals, Blair had to get into the broadcasting business. This meant an upgrade of existing technology for its Blair on Air livestreaming service. Previous performances were shot with one fixed camera situated at the back of the performance halls, with no option for close-up shots or multiple camera angles. As an alternative to attending a live performance or for archival recordings, this was adequate, but not if online broadcast was to become the school’s sole avenue for concert attendance.

The technical crew, headed by Director of Technical Services John Sevier, decided to optimize the streaming capabilities of the Steve and Judy Turner Recital Hall, the most frequently used venue at the Blair School and the space in which almost all fall 2020 performances took place.

“We took the best parts from all our performance venues to create one high-definition streaming system.” Sevier says. “Turner Hall already had an HD camera and gear from a previous classroom upgrade. We paired that equipment with a video switcher and cable from Ingram Hall, and a personal laptop for camera control to create a basic control room backstage. A camera from Ingram and a personal camera brought from home gave us a third and fourth camera angle. Borrowing a computer from Choral Hall has allowed us to back up all of our recordings.”

For the spring semester, the technical crew is designing systems to bring all three performance spaces, including Ingram Hall, into high-definition streaming and video recording capacities.

In October, Blair took another technological leap by venturing into virtual reality recording. One of the pieces on the Blair String Quartet’s Oct. 2 recital, Break Away by Jessie Montgomery, was filmed with a 3D virtual reality camera, in addition to conventional filming. Viewers who possess VR goggles are able to experience this piece immersively at the YouTube link, as if standing in the middle of the players while they perform. (Viewers without VR goggles can still take advantage of some of the 3D effects.)

“One of the most important things that we’re doing here at Blair is reaching out to new and diverse audiences, so one of the most important starting points for that is meeting people where they are,” Candelaria says. “If you think about how so many of our young people these days are … immersing themselves in music, it’s through things like virtual reality, it’s things like gaming, it’s things like YouTube, so I think this was a really important step for us.”

Click tracks and animation

While everyone at Blair would prefer to be performing in front of live concertgoers, the no-audience format is giving the school the freedom to explore new and innovative avenues in virtual reality to bring music to its patrons.

Biddlecombe, who in addition to his role at Blair also serves as chorus director for the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, had extensive experience working with digital audio workstations and recording software when the pandemic struck. He quickly put this knowledge to good use, helping his wife, Mary Biddlecombe, director of the Vanderbilt Blair Children’s Choruses, produce the school’s first virtual concert during the pandemic. The performance was later posted on YouTube.

The performances may appear seamless, but staging them on a virtual platform requires painstaking, time-consuming work. Biddlecombe provides his singers with click tracks, audio cues that are used to synchronize live music performances to film. Using the click tracks, the students then record their individual parts and return them to the professor. Like piecing together a sonic mosaic, Biddlecombe mixes each one of these voices into a recording, ultimately producing a beautifully blended full ensemble performance.

“In the beginning, mixing together a choir performance took about two hours of work for every minute of content,” Biddlecombe says. “Fortunately, with practice, I’ve gotten a little bit faster.”

Video technology also allows for more visual creativity. Among the virtual projects Biddlecombe planned for his choristers was an animated version of composer Gian Carlo Menotti’s fable The Unicorn, the Gorgon, and the Manticore. The idea of combining classical singing with animation also appealed to Gayle Shay, chair of Vanderbilt Blair’s voice department and director of Vanderbilt Opera Theatre.

Shay already was planning to stage Maurice Ravel’s short, one-act opera L’enfant et les Sortilèges. Characters in the opera include teapots, nightingales and frogs—all of which lend themselves well to animation. Jennifer McGuire, Vanderbilt Opera Theatre’s music director, helped the students learn their parts over the summer, and she created a stripped-down score to replace Ravel’s expansive orchestration.

Students in the production did more than just record their vocal parts. They were filmed wearing green hoods, allowing Nashville-based filmmaker Kevin James Thornton to impose the students’ faces on some of the animated characters. After navigating a last-minute snag involving an unusual French copyright on the libretto, Shay posted Vanderbilt Blair’s operatic animation on YouTube in December.

The Vanderbilt Wind Symphony used the virtual environment to collaborate on a music video of composer Luis Uribe Bueno’s El Cucarrón (Pasillo) with the Symphonic Band at the University of Antioquia in Medellín, Colombia. The video opens with a goat grazing in a pastoral Colombian landscape filled with a variety of insects—el cucarrón is a type of beetle. Bueno’s rhythmically vibrant music is performed by students in Colombia and Nashville, with images of the students, who recorded their pieces separately, scrolling across the screen.

Thomas Verrier, director of the Vanderbilt Wind Symphony, has spent most of the fall semester working with his players in small rehearsal groups, limiting sessions to 30 minutes each. The full Wind Symphony, 50 students strong, is too large to rehearse together even in a space as large as Ingram Hall. But the whole group did convene one day in October for a performance, Hymn for the Innocent, that was videotaped inside Vanderbilt Stadium.

“That performance meant a lot to these students,” Verrier says, “and they will remember it for the rest of their lives.”

William Pickus, a senior majoring in trombone performance, says he feels lucky to be at Vanderbilt. “A lot of students at other schools aren’t performing,” Pickus says. “But our faculty has gone out of its way to give us a good experience.”

Biddlecombe feels the same way about Blair students. “Our students didn’t choose to go through this ordeal,” he says. “Yet they have shown us that they are resilient and equal to any challenge.”

John Pitcher is a Nashville-based arts journalist who has written for Nashville Arts, Nashville Scene and The Washington Post, among other publications. Kristin Whittlesey is the director of external relations for the Vanderbilt Blair School of Music.

Watch Vanderbilt Opera Theatre’s production of Ravel’s L’Enfant et les Sortilèges:

Watch Vanderbilt Wind Symphony members with members of the Banda Sinfónica de Estudiantes de la Universidad de Antioquia perform El Cucarrón (Pasillo):

Watch the Vanderbilt Wind Symphony perform Hymn for the Innocent: