By Dr. Arthur Williams, BA’90

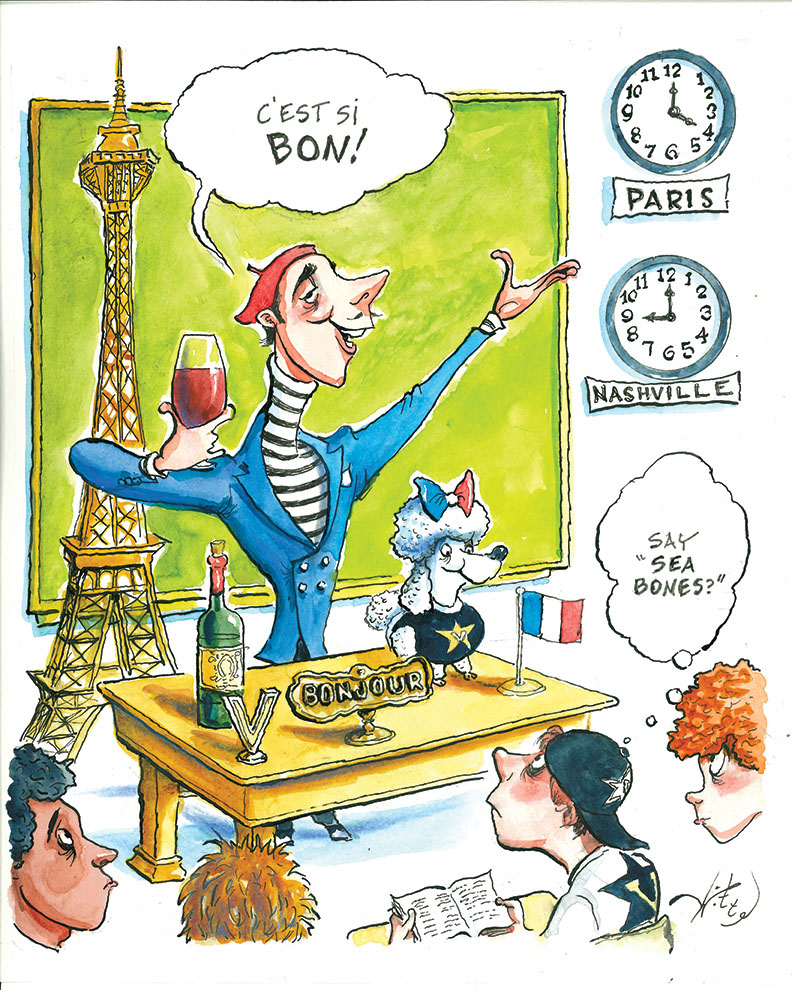

When I was a child, we summered in Paris. We lounged on the left bank, not of the Seine, but of the Big Sandy, because this was not gay Pa-ree, but Paris, Tennessee, which was a whole lot more interesting to a 10-year-old urchin like me. I’m not a French scholar by any stretch of l’imagination, but I have vivid memories of French 101 at Vanderbilt more than 30 years ago. Le professeur was the chairman of the department, unsocked and bereted, with the l’eau de Marlboreaux all over his elbow-patched jacket, his nicotine-stained beard and forefingers—the caricature of a wannabe American in Paris who stood before us.

The rest of the class hailed from places like Possumneck, Mississippi, or Wedowee, Alabama. They were barely any more sophisticated, linguistically, than I was to handle the complexities and subtleties of the French language. Yodeling banjo tunes for beginners, accompanied by an agitated howler monkey tabernacle choir, might have been less painful for our poor instructeur than that first week of French 101 in the basement of Furman Hall.

“Bonjour,” he began the very first day.

Quizzical looks met this most basic Gallic declaration.

“Bonjourrrr,” he repeated, holding out his hands, pleading for a response.

Oh, so this is how it’s gonna be. We reluctantly and haphazardly returned his salutation. “Banjo to you too.”

He broke into English to warn us that from here on the class would be taught entirely in French.

“There ees no better way to learn, mezamis, than to inculcate yourself in the language,” replied le professeur, his French inflections betraying his Dayton, Ohio, origins.

Fast forward 30 years, and I feel unworthy for not mastering the French language. It’s a beautiful, if prideful, linguistic puzzle to conquer.

Recently, I found the French poet Paul Verlaine in a most unlikely place. I have always been a fan of campy World War II movies. The pinnacle of the genre occurred in the 1960s, when the horrors of the war had diminished somewhat, and yet the relics of that conflict were still workable enough to bolster the histoires de guerre brought to life onscreen by the likes of John Wayne, Robert Mitchum, Richard Burton or Henry Fonda. The most ambitious of these films, The Longest Day, catalogs the breadth of action on June 6, 1944, in and around Normandy. In the opening sequence of the film, the French Resistance is awakened to the invasion of Fortress Europe by a BBC radio operator who, among various droll messages, inserts these solemn, plaintive wisps from Verlaine:

Les sanglots longs

Des violons

De l’automne

Blessent mon coeur

D’une langueur

Monotone.

Those lines signaled to the French Underground that their liberation was coming.

Hearing the poem spoken recently on the internet lit something in my soul. The English translation does little to confer power, roughly translated as “The long sobs of the violins of autumn wound my heart with a steadfast weariness.” The somber intonation of the French and the alliteration and rhyming pattern are Longfellow-esque. The words absolutely sing to me, though my French understanding is rudimentary at best.

During the past few months, my heart has been saddled with its own languor, a propensity for the atrial tissue to fibrillate uncontrollably, though its origin has remained a mystery to my cardiologist and me. I am not that old, I have spankingly clean coronary arteries, don’t smoke, don’t drink, and though I have a stressful job, it shouldn’t result in uncoordinated cardiac conduction and rapid ventricular response.

When combined with the stresses of work and home life, I wonder, though, if the steadfast weariness, the langueur monotone, of the world and its uncertainties hasn’t contributed to my heart’s recalcitrant beating. I worry about our patch of Earth so carelessly abased by man with his plastic contrivances and noxious emissions. I fret about our état d’esprit, the echoes of Lincoln’s house divided, and the calamity that awaits should our current discord fester. These and other jangled chords wound my heart with a steadfast weariness.

I remember the old days of my freshman year, and while I don’t weep, as Verlaine admits in the second stanza of his poem, I do thank those educators in Nashville for instilling the whispers of global thinking into my formal education. The way forward from this country’s collective despondency, and a return to some sense of harmony from our own autumnal fiddling, is dependent upon empathetic minds, conservative and left-leaning, coming together at places like Furman Hall for global studies, for reflection and respectful debate on our culture and our ethos—and maybe even for the appreciation of a foreign tongue and its transcendent voices.

Back then, for me, Vanderbilt was a place that required learning a foreign language with other unlikely linguists who suffered alongside. Now it has become a statement of account, a portfolio, whose dividends of that liberally parsed learning are maturing some 30 years later. Thank you, Vanderbilt, from an old surgeon looking for meaning in a janky EKG and finding it in the poetry of the French laureate Verlaine.

Merci beaucoup, Vanderbilt.

Dr. Arthur Williams, BA’90, is a surgeon for the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Cincinnati. His creative writing has appeared in numerous outlets, including Kevinmd, General Surgery News and Doximity. He is also the author of The Surgeon’s Obol, a novel about the rigors of surgical training.