One of the world’s foremost experts on coronaviruses, Dr. Mark R. Denison, shared his research and insights into COVID-19 during a webinar on Dec. 14.

Hosted by Chancellor Daniel Diermeier, more than 1,700 alumni, students, faculty, staff and community members joined the live virtual presentation, which highlighted Denison’s lab and the vital role it has played in battling COVID-19. Denison is the Edward Claiborne Stahlman Chair in Pediatric Physiology and Cell Metabolism, professor of pathology, microbiology and immunology at Vanderbilt University and director of the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

The Denison Lab has been funded for more than 30 years by the National Institutes of Health to investigate the replication, pathogenesis and evolution of coronaviruses, including SARS, MERS and COVID-19. This year it also received generous funding from The Dolly Parton COVID Research Fund. Since he began studying coronaviruses in 1984, Denison’s lab has made several seminal discoveries in their biology, and in creating antivirals and vaccines.

“The Denison Lab led the development of the COVID-19 antiviral remdesivir, which was for many months the only widely available and known treatment for COVID-19. He also was the first to show human antibody response to the Moderna vaccine,” Diermeier noted in his opening remarks.

Denison’s presentation explored why COVID-19 emerged, his lab’s discoveries and an explanation of how mRNA vaccines—such as those by Pfizer and Moderna—work.

“I get emotional about the impact of this virus on people I know…on friends and neighbors whose families have been affected, who have lost loved ones with this, watching my colleagues in the hospital and the work they do,” Denison said. “I get angry when I see people denying it because I know these viruses. I know them inside and out. But, at the same time, we have effective antivirals and treatments within six months, and we have vaccines within nine months. This is unbelievable, and yes, we should take them if we can.”

Denison explored several key questions during the webinar, including:

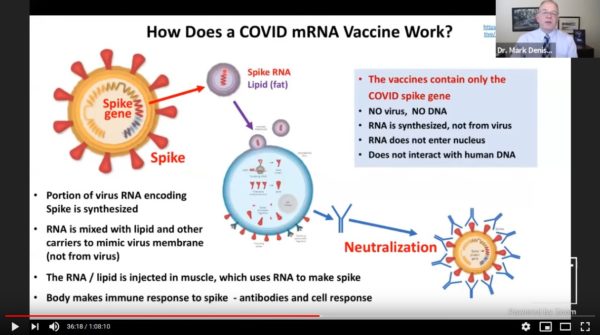

How does a COVID mRNA vaccine work? Is it safe and effective?

Denison noted that while there are several types of COVID-19 vaccines in development, the first two, from Pfizer and Moderna, are mRNA vaccines. These vaccines are unique because they are synthetic and do not contain any of the coronavirus itself.

“The (Pfizer) vaccine overall is 95% effective…that’s stunning efficacy,” Denison said. “We’re really happy with the flu vaccine that has a 60 percent efficacy, we think that is fabulous.” He also underscored that these vaccines were created with great speed in part because the science and research methodologies behind them were already in place and were bolstered by an infusion of monetary support. However, he emphasized that all FDA efficacy and safety guidelines were strictly adhered to.

Where did this novel coronavirus come from?

“We’re not going to find a smoking gun. This is now a human virus, and it’s humans spreading it to other animals as well,” Denison said, while explaining that it most likely came from a bat or a pangolin. He also stressed that the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (which causes the disease COVID-19) is too complex to have been engineered in a lab.

Denison explained that every mammal species that has been studied is known to shed coronaviruses, sometimes asymptomatically, and the potential for these viruses to circulate is increasing.

Why did SARS-CoV-2 spread from animals to humans?

Several factors, Denison noted, cause these viruses to spread and thrive across species, including an increasing human population, which has cascading effects on climate change and animal habitats. Wild animals in human diets and travel are also factors that provide opportunities for the novel coronavirus to thrive.

“For those of us that have worked in the field for so long, it’s a shock how severe it is, but it’s not a surprise that it happened,” Denison said, noting the pandemic potential of zoonotic viruses, or viruses from animals. It was the emergence of SARS in 2003 and 2004 that initially made scientists aware of “the profound possibility of what coronaviruses could do.”

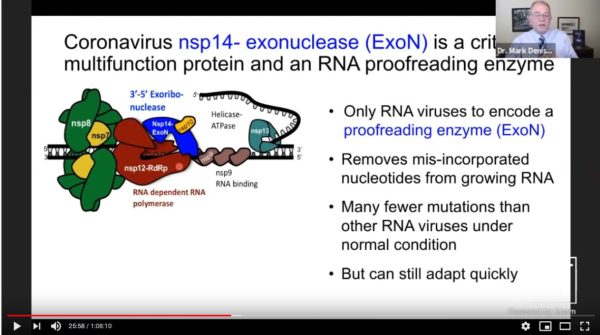

Why are coronaviruses so complicated?

Coronaviruses have the largest and most complex genomes of RNA viruses, Denison explained, which should theoretically make it more difficult for them to survive and evolve. However, a seminal discovery by the Denison Lab in 2007 revealed that coronaviruses are the only RNA viruses that have proofreading enzymes that can “fix” mistakes it makes as it replicates.

This discovery prompted Denison’s lab to look for drugs that could inhibit or bypass the coronavirus’s proofreading ability and slow down its replication. For six years they led the preclinical development of two such drugs, remdesivir and molnupiravir.

“This virus is remarkable. It may be absolutely unprecedented in human history,” Denison said, “including the 1918 flu pandemic, because of its adaptive capacity and what it’s doing, how it’s moving through and the kinds of variable disease it’s causing.”

The presentation concluded with a question and answer session touching on several topics, including the intensity of the pandemic, to which Denison underscored: “We have to continue to pull together, that’s the only way that we can stop it.”

A recording of the entire event is available here.