View the entire lecture on YouTube here.

Drawing on granular, nearly real-time data from sources like credit card companies and remote learning platforms, economist Raj Chetty highlighted some of the economic and social inequalities being exacerbated by COVID-19 as part of a virtual lecture on Oct. 22.

The event—attended by several notable local, state and national policymakers—was hosted by Vanderbilt University Data Science Institute, department of Economics, Public Policy Studies program, and nonpartisan public policy research center The Sycamore Institute.

Vanderbilt Chancellor Daniel Diermeier introduced Chetty, noting that the event was an example of the collaborative, One Vanderbilt spirit of the university.

“Our interdisciplinary institutes and programs not only connect faculty from across the university to explore new ideas and initiatives, but they also partner with external groups like the Sycamore Institute to pursue innovative thinking on a local, statewide and national level,” Diermeier said.

Chetty, the William A. Ackman Professor of Economics at Harvard University, is the director of Opportunity Insights, an interactive tool that visualizes real-time economic, employment and business activity data across the United States down to the neighborhood level. Chetty said this kind of data gives a far more detailed picture of our economic reality than do traditional indicators, such as quarterly GDP numbers.

“When we only look at a national picture—what economists have done in the past because of data limitations—you miss a tremendous amount,” he told the virtual crowd. “Issues in Tennessee are different from North Carolina, and Davidson County issues are different than other parts of the state.”

Health crisis, economic activity

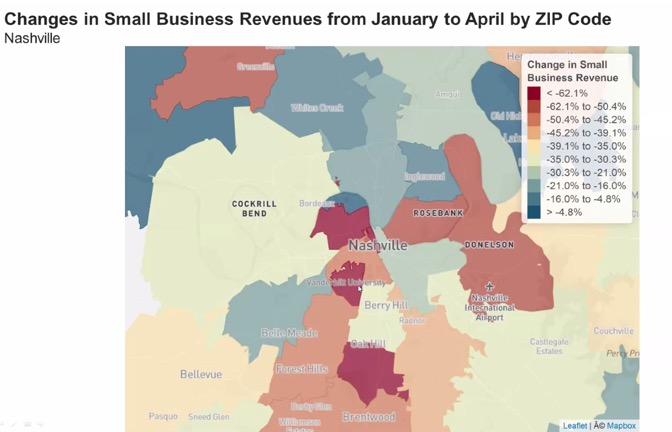

In Nashville, and in other communities across the country, Chetty showed that the vast majority of spending reductions during the COVID-19 crisis were driven by high-income households limiting their in-person activities, such as dining out or shopping. As a result, businesses in higher-income areas suffered more than those in less affluent areas where fewer people could afford to stay home in self-isolation.

“Usually we see less affluent areas hit hardest,” Chetty explained. “In this crisis it is flipped because the origin of concern is health-related.”

Chetty said this type of data could provide early signals of a jobless recovery, where spending seems to have recovered, while employment has not. For example, the COVID-19 crisis may hasten shifts to greater online spending and automation, which could affect hiring.

Mitigating the economic damage?

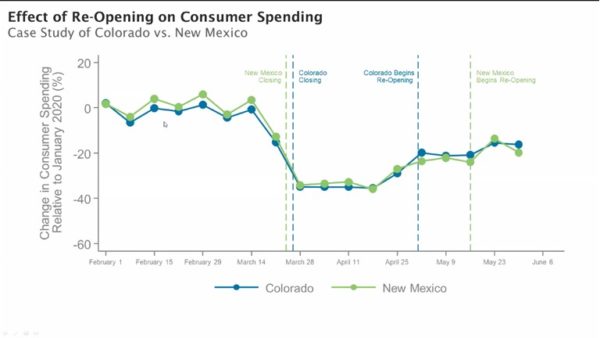

Using similar data sets to examine the effectiveness of state-ordered shutdowns, Chetty finds no meaningful economic differences. Regardless of policies, people tend to self-isolate in the face of a health threat, such as when COVID-19 cases surge.

“The fundamental reason spending fell is not because of constraints imposed by the government,” Chetty said. “It’s because lots of folks, in particular high-income folks, chose to self-isolate and spend a lot less.”

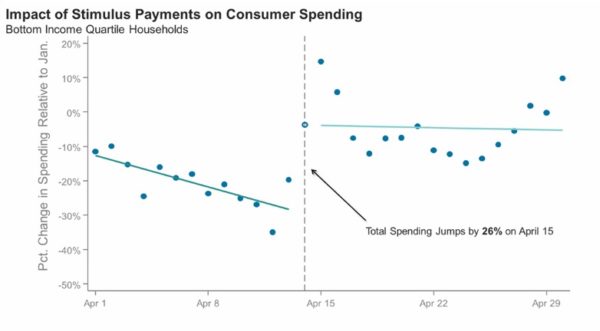

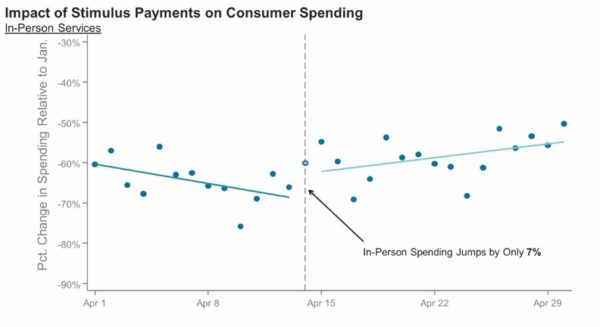

Stimulus payments this spring also did not deliver much of their intended impact, according to the data. While spending jumped by 26 percent among low-income households within two days of checks being deposited on April 15, most of that was for durable goods such as refrigerators and other major appliances, Chetty said. Yet, the payments were intended to offset the decline experienced by businesses that relied on in-person spending. There, the stimulus payments only resulted in a 7 percent increase among low-income households.

“That is potentially problematic in terms of employment because the money is not going back to the businesses that laid off the workers,” Chetty said. “Even if you look at a state like Tennessee, where spending, on average, has gotten pretty close back to baseline levels, if you were to look at employment levels in Tennessee, you would see that they are still 20 percent below baseline, in particular for low-wage workers.”

Similarly, the approximately $500 billion Paycheck Protection Program turns out to have increased employment by only 2% with a price tag of $300,000 per job saved.

“There were lots of firms that used the Paycheck Protection Program who were not going to lay off any workers anyway,” Chetty said. “Think about a small law firm that is able to provide services remotely and was not going to lay off that many workers to begin with, but why not sign up for the Paycheck Protection Program? It’s free money from the government.”

The pandemic’s long-term effects

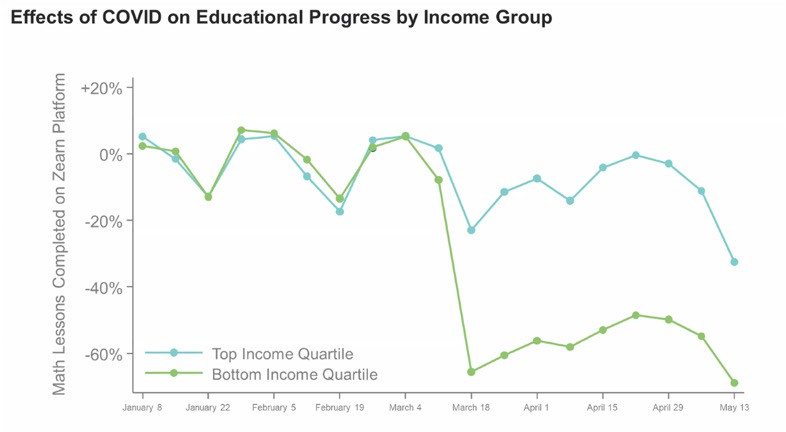

The long-term effects of the pandemic are not limited to economic well-being, Chetty said. Data on education “illustrates that a short-term temporary shock may have a scarring effect of recession, where we continue to see impacts down the road as we see kids learning less in school.” Chetty noted that while his data looks at disparities by income, racial and ethnic disparities along those dimensions are impossible to ignore. “When you look at data from a long term perspective, short term impacts exacerbate long term disparities we already have in the economy, like racial inequity,” Chetty said.

Chetty said he draws encouragement from the idea that all politics are local, suggesting that street-level data can help policymakers replicate successful programs in other areas.

“There is a science to economic opportunity,” he said. “And we’re getting closer to having the tools to figure out what that science is.”