By S. Tremaine Nelson, BA’04

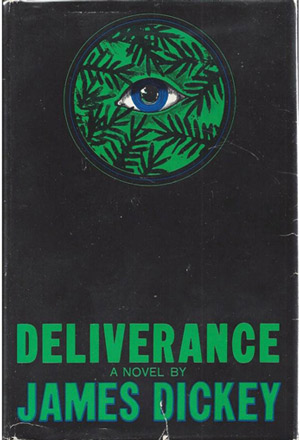

Deliverance—the debut novel by James Dickey, BA’49, MA’50—reached the polished age of 50 years old in the spring.

First published in 1970, the novel was a critically acclaimed bestseller and boosted the growing celebrity of its author. However, the 1972 film, which Stephen Farber of The New York Times called the “most stunning piece of moviemaking released this year,” quickly eclipsed the novel in the consciousness and imagination of the American movie-going public. Today if you search for “Deliverance,” you must scroll and click into the second page of Google results to find any lead articles about the novel—dominated so thoroughly on the internet by the film—making it easy to wonder if the novel will slip out of print, quietly, its semicentennial unheralded.

Before the publication of Deliverance, James Dickey already had established himself as a poet with his collection Buckdancer’s Choice, which won the 1966 National Book Award for Poetry. In his interview with The Paris Review in 1976, Dickey spoke knowledgeably about his place in the poetic tradition of Vanderbilt: He knew that he was, on one hand, heir to it, while also apart from it, admitting that there was “no sense in which it could be said that [he] was a latter-day Fugitive or Agrarian.”

He spoke fondly of having studied with Monroe Spears, BA 1919, who later edited The Sewanee Review, and Donald Davidson, BA 1917, MA’22, a Fugitive scholar who previously had taught Robert Penn Warren, BA’25. In the rapidly changing cultural and political climate of the early 1970s, Dickey was a product of an earlier time: His outspokenness, coupled with the notoriety of Deliverance the film, may have hastened the decline of his novel’s reputation, despite its initial critical success.

He spoke fondly of having studied with Monroe Spears, BA 1919, who later edited The Sewanee Review, and Donald Davidson, BA 1917, MA’22, a Fugitive scholar who previously had taught Robert Penn Warren, BA’25. In the rapidly changing cultural and political climate of the early 1970s, Dickey was a product of an earlier time: His outspokenness, coupled with the notoriety of Deliverance the film, may have hastened the decline of his novel’s reputation, despite its initial critical success.

His attitude toward women, especially his fellow writers, didn’t help his public image. In dialogue with The Paris Review, Dickey went on record as saying that the “women of the South have brought into American literature a unique mixture of domesticity and grotesquerie,” adding that “their scope is limited to the local and domestic with, in some cases, an admixture of the grotesque.” He did acknowledge the greatness of Carson McCullers, Eudora Welty and Flannery O’Connor, but in the same breath offered the appalling verdict on the fate of Sylvia Plath and her art, saying “She’s not very good. She’s just someone who killed herself out of literary desperation.”

Today such a comment would end a male writer’s career in a single retweet; in the late 1970s, it took a bit longer, but in the end Dickey faded from the esteem he once had enjoyed in the eyes of the literary public. The question at hand is whether a new generation, unfamiliar with Dickey’s reputation, may be capable of reviving—and reinvigorating—a new wave of readers to reappraise Deliverance’s worth as a novel.

In the book, four suburban Atlanta men undertake a rafting trip in rural North Georgia on the fictional Cahulawassee River. In the woods the protagonists encounter two local men—referred to as hillbillies or mountain men—who assault and rape a member of the rafting party at gunpoint. Michael Kreyling, Vanderbilt professor of English, emeritus, has suggested that the “pursuit and action writing is excellent … deserving of comparison with Hemingway’s Caporetto retreat sections in A Farewell to Arms.”

As for posterity and a generation of new readers, however, Kreyling says that any “relevance Deliverance will have going forward is in its depiction of sexuality.” In its predatory and possessive power dynamic, the novel offers a nightmarish alternative to diverse sexualities and genders more commonly portrayed in fiction today than in Dickey’s time.

The question at hand is whether a new generation, unfamiliar with Dickey’s reputation, may be capable of reviving—and reinvigorating—a new wave of readers to reappraise Deliverance’s worth as a novel.

Looking deeper, though, this is very much a novel about a continuum of masculinity. A richness of nuance and complexity exists in the relationship between the narrator, Ed Gentry, and his hypermasculine friend Lewis Medlock, a homoeroticism that William Thesing and Theda Wrede (co-editors of 2009’s The Way We Read James Dickey) and other 21st-century critics have begun to explore via the lens of queer theory and feminist theory.

Deliverance may lend itself to a naturalist, environmentalist reading, as well; the narrator, for example, calls out the “pieces of metal, engine parts, and the blue and green blinks of broken bottles”—things that sully the natural landscape, which the narrator elsewhere describes in its raw unsoiled beauty. Kreyling describes this as a “proto environmentalism [that] might redeem the novel.”

The environmentalist reading of Deliverance has not yet gained the same traction the book has seen in gender-identity criticism, but the prose descriptions of the river and its environs—noting the hydroelectric takeover by the Tennessee Valley Authority—do lend themselves to complex analysis in their own right. The novel also captures the psychological divide between urban and rural America in the early 1970s, the red-vs.-blue mentality that has only deepened in the past 50 years.

Ed, the novel’s narrator, says it plainly: “There is always something wrong with people in the country.” Using the words “sleepy and hookwormy and ugly,” he judges the town in saying, “Nobody worth a damn could ever come from such a place.” Deliverance provides the psychological topography of our modern political landscape—in the extreme—even as it fails to provide a means of reconciling the enmity between parties.

Fifty years later, finally it may be time to give this novel another chance. Deliverance offers too much relevance to contemporary American culture to let it slip past us, out of print.

If readers no longer purchase the book in quantities that justify a rerelease—Dickey’s daughter, Bronwen Dickey, reported via Twitter that a “50th anniversary edition is in the works but far from a certainty”—then it may fall upon the academic community in universities to reconsider the book’s merit. Assigning the text in courses on Southern literature, environmental studies or LGBTQ studies may infuse the text with enough market traction to push its publisher to give it a new marketing strategy to reach a new generation. It’s possible the book’s next wave of young literary enthusiasts has never even heard of Burt Reynolds and his black leather vest—and never will.

It’s worth a shot.

S. Tremaine Nelson, BA’04, is a former fiction reader at The New Yorker.