By Kevin Jones

Last spring, as many Americans anxiously locked down against the blooming COVID-19 pandemic, a sizable number of Kentucky residents found a balm in their governor’s nightly briefings. His 5 p.m. updates became appointment television, with many in the Bluegrass State, and even beyond, pouring a cocktail and settling in for their daily dose of statistics, mandates, gentle scolding and reassurance.

“We will get through this,” the governor told them most every night, “and we will get through this together.”

The governor’s fans responded by making him something of a rock star, vaulting him into national headlines and plastering his face on memes, T-shirts and socks. They praised his combination of firmness, compassion and authenticity. Some praised more than that, calling the chief executive “a hot Mister Rogers,” as well as endearments not quite fit for an alumni magazine.

And then, this happened:

On a muggy Sunday during Memorial Day weekend, protesters objecting to the governor’s coronavirus-related restrictions on life and business marched to the doors of the Beaux-Arts mansion in Frankfort, where the governor lives with his family, and demanded his resignation. Some carried guns. Afterward, several protestors hung the governor in effigy from a shade tree, as loudspeakers played an acoustic version of “God Bless the U.S.A.” Stuck to the scarecrowish likeness dangling from the noose were the words attributed to the assassins of Julius Caesar and Abraham Lincoln: Sic semper tyrannis. Thus always to tyrants.

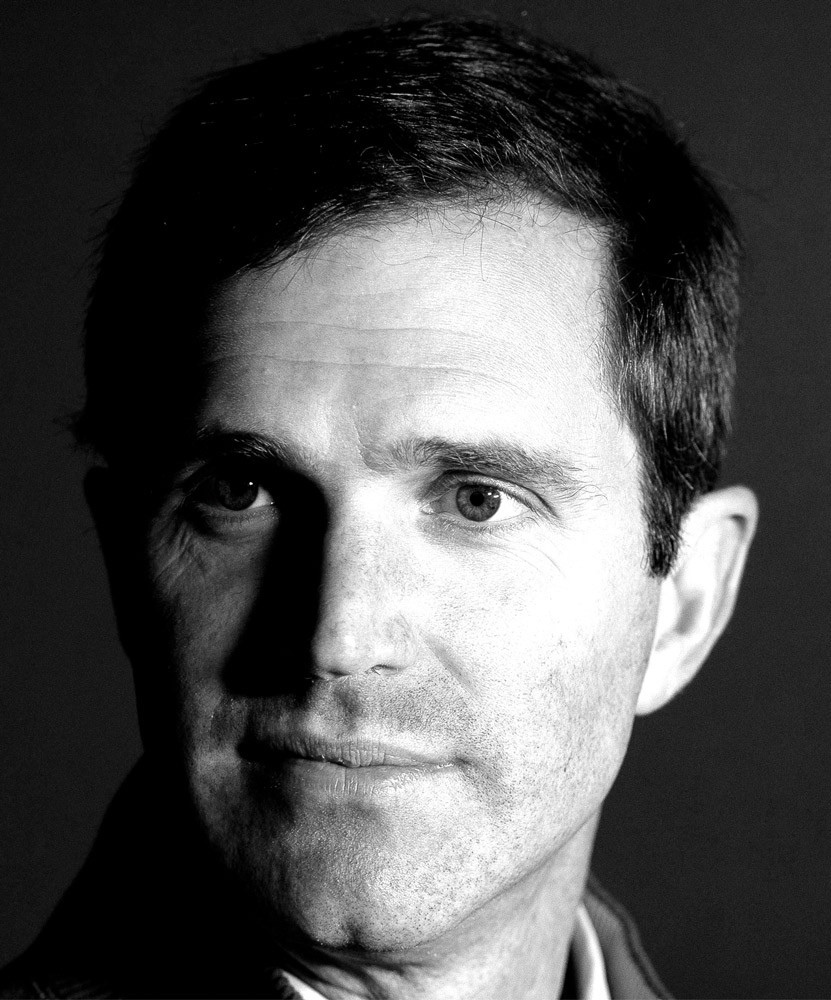

Working between those extremes—celebrity-grade adulation on one side, vitriol with violence on the other—is Andy Beshear, BA’00, the Vanderbilt alumnus and first-term Democratic governor of Kentucky. He was elected last November by a margin as thin as a surgical mask, just in time to steer his largely Republican state through a runaway pandemic, the resulting economic damage, and America’s most consequential reckoning with racial injustice since the 1960s.

Interviewed by phone in July, during a week when Kentucky was recording some of its highest COVID-19 numbers to date, Beshear conveys the mix of resolve, kindness and calm—reminiscent of a certain type of youth pastor—that had won him a following. He seems keenly aware of what is at stake in his job, observing plainly, “It is a time when the decisions I make, with good public health input, are decisions that result in life and death.”

Beshear says his approach to governing, and his willingness to endure the hosannas and brickbats of public office, were shaped by several influences: his faith, his desire to give his children a decent future, and his experience at Vanderbilt.

DISCOVERING HIS ‘WHY’

Andy Beshear grew up the son of a politician. His father, Steve, served as a Kentucky state legislator, attorney general, lieutenant governor, and, in the 2000s, a two-term governor. Yet when Andy was 10, his father lost his first bid for governor and would not win another election until Andy was 30.

“I grew up half my childhood in a political family, and the other half, thankfully, in a much more normal one,” he says. Still, by the time the younger Beshear hit adolescence, he felt running for office was expected of him. So he threw his hat into numerous rings and met with spectacular failure.

“Middle school? Lost ’em all. High school? Lost ’em all,” he recalls. “I did a Youth in Government election and came in third out of three. It’s difficult to do that, but I managed to pull it off.”

What he lacked, Beshear says now, was a cogent desire to create specific change—what he calls the “why” of seeking office. Then came his junior year at Vanderbilt, where he was a Sigma Chi majoring in anthropology and political science, and learning, as he puts it, “to think critically and creatively.” He made a bid to be president of Interhall, the body governing student-life programming (which has since merged with the Student Government Association). It was the first election he won, and Beshear attributes his success to finally discovering his why.

“The why was trying to address everyday concerns for students,” he says, including a spate of deaths from drunk driving, safety for students walking from parking lots to dorms at night, and a need for social programming that helped more students make lasting friendships. Among other changes, Interhall under Beshear enabled students to charge taxi fares on their Commodore Cards, as an incentive not to drink and drive.

“I got a lot of satisfaction out of making a difference,” says Beshear. “I didn’t think that would lead me to run for other things, but it certainly taught me that why you put yourself up for office is what drives you to be successful.”

After graduating from Vanderbilt, Beshear earned a law degree at the University of Virginia. He practiced international law in Washington, D.C., before he and his wife, Britainy, returned to Kentucky, where he made a name as a litigator for the firm where his father had practiced. In 2013, Beshear announced his candidacy for Kentucky attorney general. He was elected two years later by a margin of just 0.2 percentage points.

As Kentucky’s lawyer, Beshear sued opioid makers and was a gadfly to Republican Gov. Matt Bevin, suing Bevin over moves to cut funding to state universities and reduce pension benefits for state employees, among other initiatives. Then in 2019, Beshear took on Bevin in a bare-knuckle race for the governor’s seat. When the ballots were counted—and recanvassed—Beshear prevailed by just 5,136 votes.

“Gov. Beshear demonstrated his toughness during the campaign, and that paid off in a hard-earned victory,” says John Geer, a professor of political science at Vanderbilt who is also the Ginny and Conner Searcy Dean of the College of Arts and Science. “What’s particularly impressive about the victory is that Kentucky had been reliably red leading up to the election, with the state voting overwhelmingly in favor of President Trump in 2016. Beshear clearly had broad appeal as a candidate and was able to make inroads with many of those right-leaning voters.”

In a state where Republicans hold a supermajority in the General Assembly, Beshear set about bringing his opponents along with him on priorities like public education, universal health care and more.

“Now my why is trying to create an opportunity for all my Kentucky citizens to be successful,” he says. “For me, that’s the belief that health care is a basic human right. It’s also a belief that education is the way to transform our state and to transform our families.”

A TEST OF HUMANITY

But Team Beshear was barely done celebrating its election victory when 2020 began delivering its harsh blows. First came COVID-19. Then came the police killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Breonna Taylor in Louisville, and other African Americans around the country—and the seismic demands for racial justice that followed.

Beshear says he is responding to calls for racial equity by working to eliminate health disparities along racial lines, prioritizing African American residents in his push to enroll every Kentuckian in a health care plan. His administration is also reviewing race-based gaps in hiring and wages among state workers, among other measures, he says.

“Trying to address as many of those systemic inequalities as possible, I think that’s the role of a governor,” he says.

Yet whatever else Beshear might want to accomplish, it was plain in late July that the coronavirus would continue to demand most of his attention—politics be damned.

“The type of leadership that’s needed right now is one where you put any concerns about your own political future on the shelf and make the very best decisions for your people,” he says. “This is one of those times where my job is to get our commonwealth through this, and it will be the most important thing I’ll ever be asked to do.”

He acknowledges that getting Kentucky through the pandemic requires winning over at least some of his critics. For that, he says, he draws on lessons learned at Vanderbilt.

“Studying anthropology taught me the importance of trying to understand where other people are coming from, and trying to establish good communication with people who may come from a very different place, but that you may have more in common with than you initially believed,” he says.

Asked if he expected the searing reaction he has gotten from some Kentuckians who disagree with him—particularly the ones who show up carrying rifles—he chuckles.

“Probably more than anybody, I thought I knew what I was getting into,” he says, alluding to his father’s years in office. “But I couldn’t have been more wrong.”

“How well we do against this virus is going to be about how we put any divisions on the shelf and live for each other.”

Still, he says, his work is gratifying, and he is more convinced than ever that there is “more love than hate in this world … where the good far outweighs the bad.”

“Most days that I have are good,” he says, describing the outpouring of support, including from some Republicans, that followed his being hung in effigy. After Beshear pulled his young son, Will, from a little league tournament because he feared teams and fans were not distancing enough—and after he disclosed that someone had posted vaguely menacing photos of Will snapped during other baseball games—Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher and former Commodore student-athlete Walker Buehler, ’16, sent Will an autographed baseball.

In all, Beshear says the pandemic has convinced him that America is far more unified than angry protests or the free-fire zone of social media suggest.

“Prior to the outbreak we were as divided as I’ve seen … [but] I think COVID has taught us that the divide, and the intensity some people felt about it, weren’t as important as we thought,” he says.

“I think COVID-19 is a test of our humanity,” he continues. “Can we be the kind of really good people this moment requires? How well we do against this virus is going to be about how we put any divisions on the shelf and live for each other in ways that our morals and faith should compel us to.”

Here, too, Beshear traces his perspective and civic spirit in part to his Vanderbilt years, where, he makes a point of noting, he formed friendships that are still among his closest.

“At Vandy, by and large, I saw a community that looked out for one another. It was the type of place where strong bonds were made, and people tried to help each other out.

“And that,” says the beloved and reviled governor of Kentucky, shortly before rushing off in pursuit of his why, “is exactly what we need in our world right now.”

Kevin Jones is a Seattle-based writer who writes for corporations, nonprofits and universities. His work often focuses on sustainability, corporate social responsibility and higher education.

Steven Reed: The Business of Governing

In the early weeks of COVID-19’s arrival in the U.S., Steven Reed, MBA’04, the newly elected, 46-year-old mayor of Montgomery, Alabama, peered into the future and did not like what he saw. He understood that testing levels in his city were insufficient, especially among African Americans and rural residents. So Reed picked up the phone and dialed not FEMA, not the CDC, but Hyundai.

“When I read about the steps South Korea had taken to flatten the curve [of COVID-19], I thought it was well worth the effort to ask Hyundai to send us tests and equipment, not only for Montgomery, but also for the state of Alabama,” Reed explains. Hyundai, whose only U.S. factory is in Montgomery, agreed to send 10,000 kits.

Reed cites his decision to contact the automaker as just one example of how he applies his education from Vanderbilt’s Owen Graduate School of Management.

“Every day I draw on that knowledge,” says Reed, who still has the numbers of some of his Vanderbilt professors in his phone.

Running on an ambitious agenda in the fall of 2019 that stressed unity and proposed transforming virtually every aspect of civic life—education, public safety, economic opportunity, health, culture and more—Reed was elected Montgomery’s first African American mayor.

It’s a weighty honor in a city whose population is 60 percent Black and whose history embodies the story of American race relations in microcosm. Reed says he is intent on changing the world’s perception of Montgomery as a city mired in the Old South.

“I think Steven deserves to be put on the same kind of pedestal that we put Owen School alumni who are CEOs and company founders,” says David Owens, professor of the practice of management and innovation at Owen and the Evans Family Executive Director of the Wond’ry, Vanderbilt’s Innovation Center. “We were founded as a ‘management’ school very deliberately, without regard for what type of organization was to be managed … Steven is a real success story and a model of leadership.”

— Kevin Jones

To read the full story that ran in the summer 2020 issue of Vanderbilt Business magazine, go to vu.edu/steven-reed.