By George Spencer

On election night, Sam Feist, BA’91, was prepared to perform one of his more important duties as head of CNN’s Washington Bureau.

Since 2004, he had called the winner of every presidential race for the network hours after the polls closed, based on the recommendation of his team of statisticians and political scientists. This most recent contest, however, proved to be anything but typical, as election officials in key battleground states required days to tally the unprecedented number of mail-in ballots.

CNN had prepared for this scenario and had anchors, reporters and staffers primed to continue its election coverage 24 hours a day, for days straight. The planning paid off: Feist and CNN were the first to call the race in Joe Biden’s favor on Nov. 7, edging out other news outlets by minutes. CNN outpaced its competitors in viewership and online traffic, averaging 5.9 million viewers during the week and a record 116 million visitors to its website the day after the election.

“In the run-up to the election, we spent a lot of time telling viewers there was a good chance we wouldn’t know the winner on election night. But we had no idea it would take five days,” says Feist. “That conversation with our viewers, both before election night and after polls closed, was really important because we knew counting mail-in ballots would take a long time and everyone had to be patient.”

This commitment to earning viewers’ trust has been a guiding principle of Feist’s 30-year career with CNN, the last nine of which he has been bureau chief and senior vice president. During those three decades, he has had a hand in much of the network’s political coverage and programming, and has won three Emmy Awards. He helped conceptualize and was the founding executive producer of The Situation Room, the daily newscast now in its 15th year, and has produced and managed the production of other CNN political programs, including Crossfire and State of the Union.

Currently, Feist is one of six Vanderbilt alumni working in the network’s Washington Bureau. Among them is Kyle Blaine, BA’13, CNN’s senior campaign editor, who in the lead-up to November’s election worked around the clock in what he calls “the red-hot center of the sun” overseeing a team of reporters, writers and staffers who covered the Trump and Biden campaigns.

“We had been preparing ourselves and our audience for an election that could last days or weeks, and so when we didn’t have a winner on election night, we were ready. It ended up being a marathon,” says Blaine, who joined CNN four years ago after serving as deputy politics editor for BuzzFeed. “And through it all, we wanted to project calm and clarity when we could: Votes are being counted, here is what we are seeing, and this is what it means for each candidate’s path to 270 electoral votes.”

Like Feist, Blaine cut his teeth as a journalist at Vanderbilt, though there is no formal journalism program at the university. What more than made up for it were engaging classes in the humanities, most notably those led by the university’s renowned political science faculty—both Feist and Blaine were poli sci majors—and unparalleled learning opportunities outside the classroom, such as writing and editing for The Vanderbilt Hustler student newspaper.

Of the latter, Feist says writing Hustler stories that shined a light on uncomfortable truths about the university and its leadership was “a terrific lesson in accountability journalism that applies to what we do now.” Feist’s undergraduate experience at Vanderbilt laid the foundation for his current success, he says, and it’s the reason he has been so inclined to hire fellow graduates of the university, including Blaine and others.

“Some of our strongest producers and journalists happen to be from Vanderbilt,” Feist says proudly. “It prepares you well to cover the world.”

MORE THAN A TV NETWORK

CNN, the world’s first 24/7 cable news channel, launched in 1980 and now has a global reach of 402 million households. “I don’t think we’ve ever been stronger,” says Feist. With more than 500 staffers (including newly hired news assistant Morgan Rimmer, BA’20), his bureau ranks as the world’s largest—and one of the most influential—news offices. “CNN is far more than a TV network now,” says Feist, pointing to the fact that CNN Digital is the world’s “No. 1 online news destination” with a 2020 monthly average of more than 220 million unique global visitors each month.

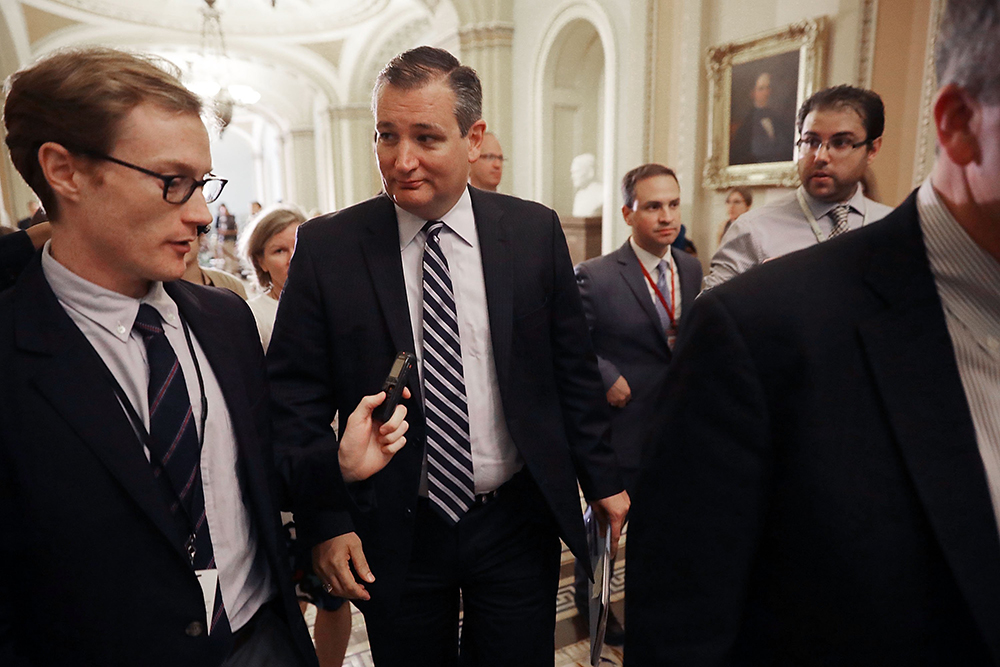

Among those seeking to expand that reach is Alex Rogers, BA’12, an online reporter who covers Capitol Hill. An English and history major, he got his professional start as an intern at The Tennessean and “fell in love” with journalism when his first article ran on the front page next to a story about singer-songwriter Taylor Swift. At CNN he covered President Trump’s first impeachment trial and reports on major legislation, something he also did at Time magazine and The National Journal until joining the network two years ago.

“One of the great joys is the immediate access you get to members of Congress,” Rogers says. “You see senators at lunch and are able to bump into them and ask questions.”

Being in the Senate chamber to watch impeachment hearings strengthened his reporting. “It was an amazing opportunity to watch history unfold,” he says. “I paid close attention to Sen. Lamar Alexander [BA’62], who was considered a crucial vote on whether the Senate GOP would vote to block witnesses and acquit the president.”

From the press gallery above the Senate floor, Rogers could look down and see exactly when the Tennessee senator picked up his pen to write something. “By being in the Senate chamber,” says Rogers, “I knew what to ask Alexander.” (No stranger to journalism, Alexander edited the Hustler his senior year and used his position to call for the admission of Black students.)

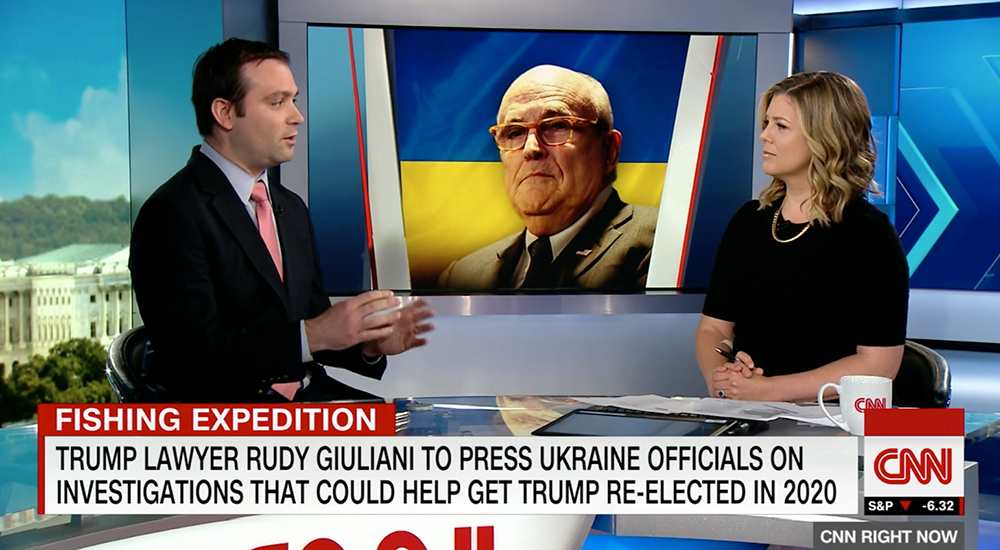

Michael Warren, BA’10, an enterprise reporter at the bureau, sometimes collaborates with Rogers, and even occasionally gets on air. A former Weekly Standard writer, he works from an “unglamorous” office due to COVID-19—a spare bedroom in his house—but his reporting is anything but confined. It crosses beats and departments to cover everything from campaigns to Capitol Hill for stories with “long tails” that have in-depth, long-term focus. Notable among them was his report on a controversial Pentagon cloud-computing contract.

“It went cold for months,” recalls Warren, a former Hustler editor and WRVU DJ who majored in economics and history. “Then it picked up. There were meetings and phone calls leading, leading, leading to all this information about cloud computing, something I never thought I’d ever need or want to know about.”

Warren also found himself on TV covering impeachment. “A few times I’d get a text from [White House adviser and Trump attorney] Rudy Giuliani,” he says. “The next thing I know I’m getting out of a meeting, straightening my tie, and going in front of the newsroom camera” for experiences that he has found to be an “odd, thrilling, exciting” part of his job.

“I’ve had to practice to get better at it,” he admits.

HOUR-BY-HOUR NEWS CYCLE

Meanwhile, Morgan Stoviak, BA’03, never appears on air—but she plays a lead role in deciding what does as the senior producer for The Lead with Jake Tapper, one of CNN’s most influential shows. For the past four years, she has put in 60-hour workweeks crafting the daily news and interview program from scratch each day. After she and three other producers hold a 7 a.m. group call, they get more ideas in an 8 a.m. call with reporters on D.C. beats and in a 9 a.m. network-wide call.

“Then I start building the show. Jake starts weighing in, and it’s a conversation with him through the day,” says Stoviak, who majored in political science like several of her Vanderbilt colleagues. “It is really driven by the news of the day. In the current news cycle, the show changes often throughout the day—and often during the show.” Even on-air, if news breaks, the team adds reports, kills reports, reacts to events and adds guests.

Stoviak thrives on instant decision-making. For example, she directed what went on-air in the control room when President Trump walked from the White House to the riot-damaged St. John’s Church in June.

“‘Who has this?’” she remembers thinking. “‘They’ve got great pictures. Go to them. They’ve got great editorial. Go to them.’ You’re going on the fly, which is for me such an adrenaline rush. There’s nothing better than doing real rolling coverage and breaking news. It was such a stunning moment in the control room, where everyone couldn’t believe what was happening. All the pieces fell into place with live overhead pictures, reporters in the crowd, and pictures on the ground.”

Stoviak, who came to CNN after four years as producer of the Fox News morning show Fox & Friends, got her start as a runner for NBC News during the 2000 presidential conventions. “I didn’t have an interest in politics or news before my first day as a runner,” she recalls. “I fell in love with it.”

Her zeal impressed John Geer, the Ginny and Conner Searcy Dean of the College of Arts and Science and professor of political science. She took his U.S. Elections class, and Geer recalls she “had huge amounts of talent.” Rogers, whom Geer calls “gifted,” took the class eight years later. This year, nearly 830 students are enrolled in an online version of the class, co-taught by Jon Meacham, Pulitzer Prize–winning author and holder of the Carolyn T. and Robert M. Rogers Chair in American Presidency.

When asked if the 24-hour news cycle is stressful, Stoviak laughs and says, “I think it’s an hour-by-hour news cycle. It makes what we do so much more important.”

A COMMITMENT TO TRUTH

One thing that Stoviak takes pride in is that Tapper’s show aims to give equal time to both sides of issues. “We try hard to be fair to both sides and be accurate,” she says. “That’s the most important thing.”

In today’s highly polarized political environment, it is perhaps inevitable that some would claim that CNN’s coverage favors one party over another, but Feist rejects that charge.

“Not only is it not fair, I believe it is not true,” he says. “I feel strongly CNN does not take sides. We work hard to practice accountability journalism on both sides. There are news channels that have contributors on one side, and other news channels have contributors on one side, and on CNN you will see both. Our audience is the most politically balanced audience, and we’re really proud of that.”

Feist acknowledges CNN’s relationship with Trump’s administration has been challenging, especially when the press pass of the network’s White House correspondent Jim Acosta was revoked. “It was an unprecedented move. We took the president to court, which was also unprecedented, and we won,” Feist says. “Yet we still deal with the White House every day.”

Overall, Feist says President Trump’s “relationship with the press was as strained as we’ve had with any president in the 30 years I’ve been doing this. … He called us ‘the enemy of the American people,’ and that was unprecedented. We had never had a president refer to the press in this way.”

Feist defends CNN’s accountability journalism, pointing to its 2014 investigation of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The Obama administration’s mismanagement worsened VA hospitals’ admissions waiting lists, which led to deaths. CNN’s reporting eventually forced the resignation of Secretary of Veterans Affairs Eric Shinseki.

“We held those in power accountable, and we made sure the truth came out,” Feist says. “That’s what journalism is. So when we held those in the Trump administration accountable, we were no more biased against Trump than we were against Obama.”

Feist compares it to the time when, as an editor of the Hustler, it was revealed that a member of the Vanderbilt Board of Trust belonged to a country club that refused to admit Jewish people or Black peopls. Feist subscribed to the same accountability journalism then as he does now as bureau chief.

“It reflected poorly on the university. I wrote story after story and op-ed after op-ed,” he recalls. In the end, the board member resigned. “I like to think our journalism helped right that wrong,” he adds.

Similarly, Blaine had his own share of scoops and learning experiences while writing for the Hustler. “Vanderbilt is where I caught the news bug, where it was nurtured and where I got to play with big and small stories—and make mistakes,” he says.

Catching “the news bug,” according to Dean Geer, has everything to do with what goes on in liberal arts classrooms. “Journalism certainly can be taught through an undergraduate major,” he says. “But it’s also true if you think about politics carefully, know how to write, and are analytical, you can do great things.”

Warren agrees, but he offers up another explanation as to why Vanderbilt graduates are making their mark in journalism, particularly at CNN. Because journalism is an extracurricular activity at Vanderbilt, he says, it brings together diverse people from different majors. That experience forced him and his colleagues to step out of their comfort zones at times and prove themselves again and again—something that is now invaluable as they navigate today’s around-the-clock news cycle.

“That wouldn’t have happened if there were an official journalism school,” says Warren. “We try to punch above our weight.”

Freelance writer George Spencer is based in Hillsborough, North Carolina.