By Elizabeth Cook Jenkins, BS’99

Years from now, Caroline Randall Williams may look back on the summer of 2020 as the time when her calling came sharply into focus. The Nashville native and Vanderbilt writer-in-residence, who is also an award-winning poet, young adult novelist and cookbook author, already had a penchant for activism in her work, exploring issues facing African American women like herself. Yet, this summer, which was marked by a racial reckoning not seen since the 1960s, inspired her in a way that no other moment in her life had previously.

In June, Williams felt compelled to compose a deeply personal opinion piece for The New York Times, titled “You Want a Confederate Monument? My Body Is a Confederate Monument.” In it, she reveals that biologically she is more than half-white, even though there are no white people in her genealogy in living memory. She also shares that her maternal great-grandfather was the son of Confederate general Edmund Pettus, a grand dragon of the Ku Klux Klan for whom the infamous “Bloody Sunday” bridge in Selma, Alabama, is named—the same bridge that provided passage for the funeral procession of civil rights leader and congressman John Lewis later in the summer.

“I think in some ways that was a lifetime coming because of the truths it was trying to tell about my body and my lived experience,” says Williams about the op-ed, which not only garnered widespread media attention but also resonated deeply with readers. “It has been really encouraging to read these letters that are coming in from everywhere. I’ve been moved and encouraged and fortified by the feedback. I’ve never been so glad that I wrote something I wasn’t sure if I should be saying or not.”

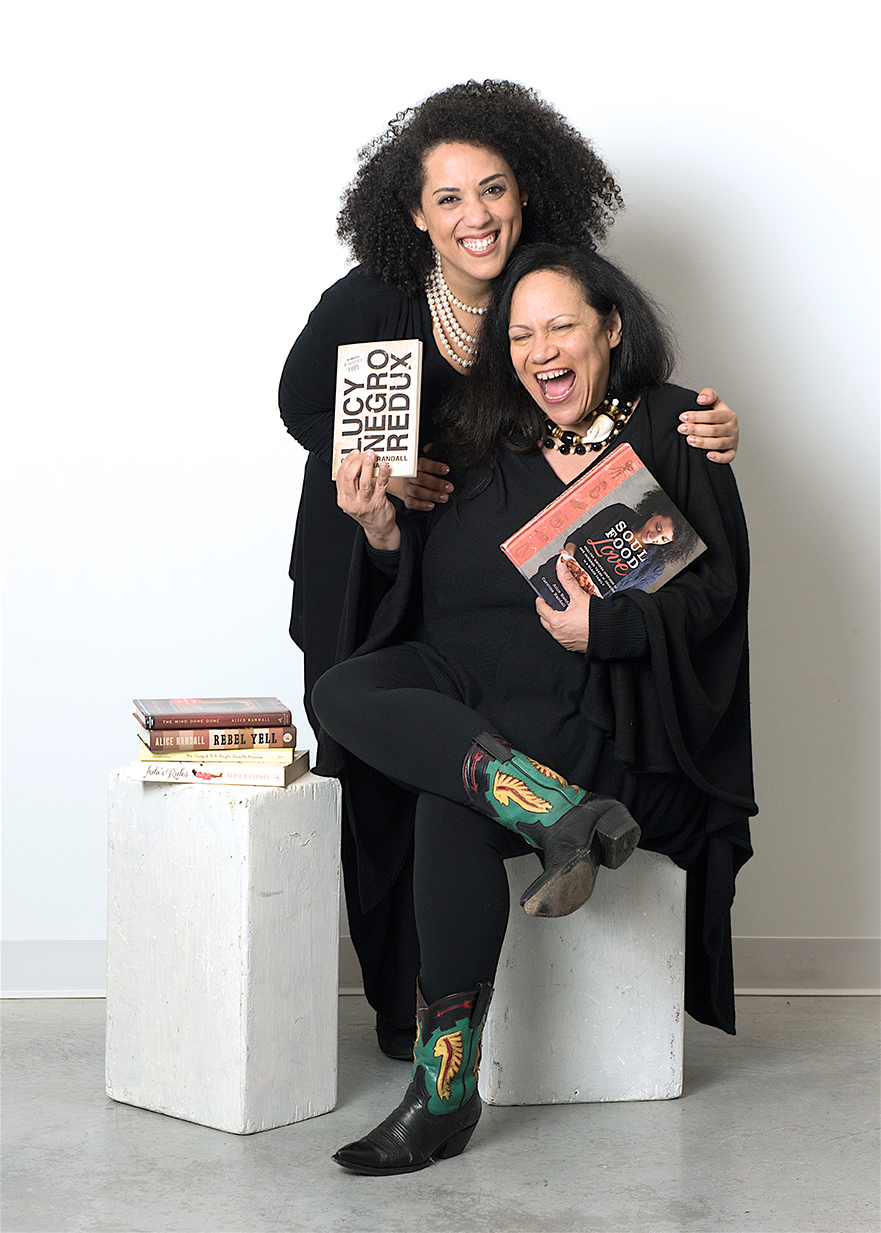

Williams comes by her artistic courage honestly. Her mother, Alice Randall, is herself a bestselling novelist, award-winning songwriter, educator and food activist, and not afraid to shine a light on complicated questions around race. However, the similarities between the two women do not end there.

Randall and Williams, who earned undergraduate degrees from Harvard University a generation apart, have written two books together: the NAACP Image Award–winning cookbook Soul Food Love (2015, Clarkson Potter) and the young adult novel The Diary of B.B. Bright, Possible Princess (2012, Turner), which won the Harlem Book Fair’s Phillis Wheatley Prize. And now the mother-daughter duo not only occupy the same campus but also share the same title. Randall, who joined Vanderbilt’s faculty in 2003, is a writer-in-residence in the Department of African American and Diaspora Studies, while Williams joined the Department of Medicine, Health and Society in the same capacity last fall.

In an interview conducted this summer, the two talked about their commonalities, their family roots and the many ways in which they continue to create and collaborate, even while physically distanced in the midst of a global pandemic.

FAMILY BUSINESS

An only child, Williams attended University School of Nashville, located across the street from the Vanderbilt campus. She watched in admiration as her mother’s career evolved, and she became privy to a daily master class on writing—in all its forms.

“My mom is an exceptional educator, as well as a brilliant writer,” says Williams. “She taught me writing while she was making a living by her pen—and she taught me well.”

True though that may be, Randall does not take full credit. “Caroline was born into a family—and I married into a family—of multigenerational artists,” says Randall, explaining that Williams’ paternal great-grandfather was Arna Bontemps, the Harlem Renaissance poet.

When Randall was pregnant with her daughter, she lived with the late Bontemps’ wife and typed on the typewriter he had inherited from his friend, co-writer and fellow Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes. “It was Grandma Bontemps who encouraged me to be a novelist and to find my voice,” Randall recalls.

As an English major at Harvard in the 1970s, Randall made a habit of listening to country music on a Boston radio station while she typed out essays for school. Born in Detroit, she had grown up with an appreciation for Motown music and lyrics, but country was new to her. Randall’s interest intensified after a friend gifted her the Smithsonian Collection of Classic Country Music, a multivolume compendium of 143 essential songs. Soon after, she pledged to move to Nashville and become a songwriter to support what she hoped would be her eventual career as a novelist.

Anyone on Music Row can attest to how hard it is to break into the industry, but Randall was determined. After a chance meeting with legendary singer-songwriter Steve Earle at Nashville’s Bluebird Café, Randall asked him to teach her his craft, and he obliged. She soon founded her own publishing company, Mid-Summer Music, which later merged with Major Bob, the label behind Garth Brooks. She continued to write and publish there until 1990, when she signed with SonyTree.

In 1994, Randall co-wrote the screenplay for a television pilot-turned-Movie of the Week called XXX’s and OOO’s, about the ex-wives of country music stars. She also penned the theme song, “XXX’s and OOO’s (An American Girl),” with the help of co-writer Matraca Berg. The feminist anthem soared to the top of the charts after Trisha Yearwood recorded it, cementing Randall’s place on Music Row, and making her the first Black woman to write a No. 1 country song.

In 2001, the publication of Randall’s provocative first book, The Wind Done Gone (Houghton Mifflin), launched her career as a novelist. The “unauthorized parody” of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind—told from the perspective of Cynara, a slave and half-sister of Scarlett O’Hara—spoke some uncomfortable truths about the Old South and became a New York Times bestseller in the process. Over the next decade, three more novels followed: Pushkin and the Queen of Spades (2004, Houghton Mifflin), Rebel Yell (2009, Bloomsbury) and Ada’s Rules (2012, Bloomsbury).

Meanwhile, in 2006, Randall began teaching Vanderbilt students subjects she was passionate about, including courses such as Soul Food as Text in Text: An Examination of African American Foodways, African American Presence and Influence in Country Music, and Real to Reel: African American Representation on Film. She also served for several years as the faculty head of Stambaugh House, living on The Martha Rivers Ingram Commons, where she was known endearingly as “Al-Pal” to the young people under her care.

“Al-Pal taught me how to foster community in a new place,” says former Stambaugh resident Monica Peacock, BA’17, who now works as a client liaison at Sotheby’s in New York. “She showed me that food is a universal language—no matter where you’re from or where you’re going, if you share a meal with someone, you’ll learn their story. Since moving to New York City, I’ve hosted a number of small, Stambaugh-inspired gatherings in my apartment and even served a few recipes from Soul Food Love. By following Al-Pal’s example, I’ve made new friends from around the globe.”

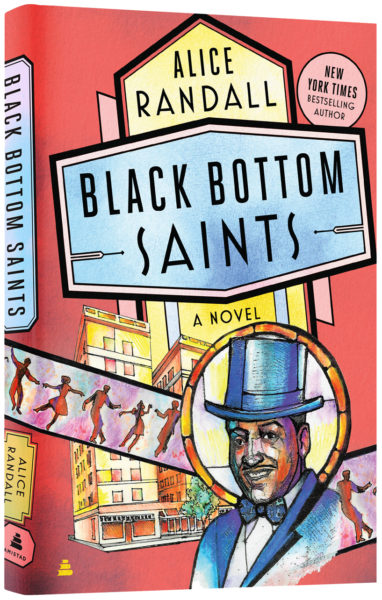

This August, Randall’s fifth novel, Black Bottom Saints (Amistad), was released. The story is set in the titular Detroit neighborhood of Randall’s youth, which was destroyed after Congress passed the 1949 Federal Housing Act.

This August, Randall’s fifth novel, Black Bottom Saints (Amistad), was released. The story is set in the titular Detroit neighborhood of Randall’s youth, which was destroyed after Congress passed the 1949 Federal Housing Act.

“In my own heart and mind, this is my strongest and most important novel,” says Randall, who dedicated it to Williams. “I had a great early editor-reader at home in Caroline, whose insights were essential to it becoming the book that it is.”

Randall’s grandparents came to Michigan from Alabama as part of the Great Migration of the early 20th century and started a business in Black Bottom. “It was a very modest business—a dry-cleaning establishment—but it was the family business,” she says. “As an economic engine, that dry cleaner eventually supported my novel writing. So the idea of being humbly and surely in a family business means that we get to work with the insight of multiple generations.

“I work with Caroline, not because she is my daughter, but because she is the best writer I know … and she takes my calls,” adds Randall, laughing. “I am very lucky that one of the finest writers I know always takes my calls.”

OLD HEADS AND NEW VOICES

Unsurprisingly, Williams considers herself the lucky one.

“When you choose a creative life, finding mentors is so important,” she says. “Knowing people in your field who have done what you want to do, who have only your best interest at heart and are prepared to share their resources, insight and access with you, is very rare. That is what you seek out, and I was born with it.

“That is just one of the great privileges of a very privileged life that I’ve had,” Williams adds. “I get to work with my mentor, who is also my mother, and who wants me to do better than she does, which is a crazy space of generosity to have with a collaborator.”

The fact that Randall and Williams are so attuned to each other’s creative sides has proven particularly valuable during the COVID-19 pandemic. The two women have remained physically distanced since the spring: Randall in a high-rise apartment downtown and Williams in her childhood home near campus. The distance, however, has not diminished their ability to collaborate. In fact, this summer the two worked on a script for a television pilot based on Black Bottom Saints, which Williams took the lead on writing.

“When you’re writing with your teacher, it can be nerve-wracking, but we’ve established more of a balance over time,” says Williams, who was signed by the William Morris Endeavor talent agency in July. “It becomes really joyful to feel like you’re pulling your own weight. I’ve enjoyed growing into that part of it.”

That arc of growth as a writer can be traced back to Williams’ graduation from Harvard in 2010 and subsequent move to Sunflower County, Mississippi, where she taught English to public school children for two years as part of Teach for America. During that time, the pair’s first joint effort, The Diary of B.B. Bright, was published.

While in the MFA program at the University of Mississippi, Williams began writing a poetry collection about the mysterious “Dark Lady” who features prominently in William Shakespeare’s sonnets. Those poems ultimately became Lucy Negro, Redux and were published by musician Jack White’s imprint Third Man Books in 2015. That same year, Williams was named one of “50 People Changing the South” by Southern Living magazine, and the culinary anthology and cookbook she co-authored with Randall also was published.

“Soul Food Love is about how we take care of the body, how we tell stories of where our bodies have been, and how we feed our bodies to keep them well,” explains Williams. “Similarly, my poetry navigates questions of race and gender identity, how those are manifested in the body, and how we create our stories.”

In 2016, Paul Vasterling, the artistic director of the Nashville Ballet, read Williams’ poetry collection and optioned the rights to adapt it as a ballet. In February 2019, Attitude: Lucy Negro Redux premiered on the stage, and that fall, Williams began teaching at Vanderbilt. Her courses this fall are COVID and Society—co-taught with Dr. Jonathan Metzl, the Frederick B. Rentschler II Professor of Medicine, Health and Society, professor of sociology, and professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences; David Wright, Stevenson Professor of Chemistry and professor of communication of science and technology; and Celina Callahan-Kapoor, senior lecturer in medicine, health and society—and Medicine, Health and the Body, a first-year seminar.

“My biggest goal when I moved home to Nashville was to not have to leave, to figure out a way to live by my pen, and to teach and grow minds,” explains Williams, who recently was included in The Root 100, an annual list of the most influential African Americans. “The fact that one of the best universities in the world is in my hometown, and that I found a home there is a crazy gift that I continue to be excited about.”

Equally exciting is the work both women are doing in their writing and in their classrooms to continue celebrating their heritage during this historic time. “Caroline and I are—independently and together—artists committed to political uplift, to empathy, and to building things better,” says Randall.

Williams’ op-ed in The New York Times aims to accomplish just that, but it does not pull any punches. The opening line—“I have rape-colored skin”—immediately grabs the reader’s attention and echoes something that Randall was getting at two decades before with The Wind Done Gone.

“The story Caroline tells is also Cynara’s story,” explains Randall. “Cynara’s father is a Confederate officer, a planter. I never came up with an amazing line like Caroline’s about ‘rape-colored skin’—if I had, I might be the most famous novelist in America—but neither Cynara nor I had that insight.”

The parallels that one can find in Randall’s and Williams’ writing speak to the common ground they share, not just as mother and daughter, but as artists who inspire one another and amplify each other’s voices. Yet, the synergy between them also is emblematic of something larger and no less profound taking place across generations at this moment in history.

“Right now, we have multiple generations—old heads and new voices—coming together from all parts of the spectrum to more effectively take the cultural conversation further,” says Randall. “And I think with these new voices we see a new grace and power. We are no longer shadowboxing the reality of racism.”

Elizabeth Cook Jenkins, BS’99, is a freelance writer based in Los Angeles.